Whimsy is as delicate as a butterfly wing. But “The Man in the Hat” sustains a whimsical tone beautifully throughout its brief running time, perhaps because co-writers/directors John-Paul Davidson and Stephen Warbeck add a touch of melancholy to keep it from becoming too cloying or cutesy. Somewhere between a dream and a fable, this is the kind of film viewers could debate for hours, pondering the meaning of the characters who keep reappearing, the mysterious framed photo, the central character who has only two lines of dialogue if you do not include an imitation of car engine noises.

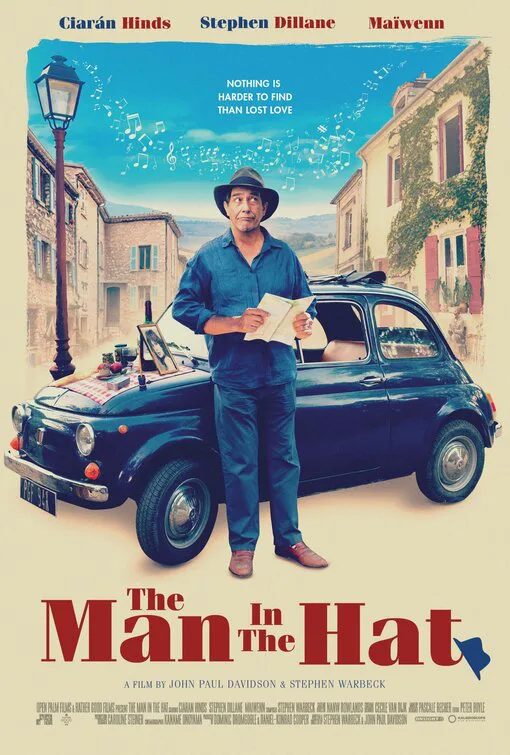

None of the characters have names, only descriptions. Ciarán Hinds plays the title character, with an endless variety of lugubrious facial expressions, and we will just call him Hat. We first see Hat sitting alone at an outdoor cafe, looking gloomy. On the table beside him is a newspaper and a framed photograph of a woman, described later in the film as “beautiful but sad.” He is there for hours, and we get the feeling he may be stuck. But five bald men get out of a Citroën Dyane and dump into the river a wrapped and taped up object about the size and shape of a dead body. The Citroën Dyane men spot Hat, who quickly decides he had better be where they are not. As they approach him menacingly, a group of nuns walk between them and by the time they are gone, Hat is, too. He drives off in his Fiat 500, the framed photo on the passenger seat behind him. The Citroën follows him, but he manages to get the Fiat onto a ferry, leaving them behind.

On the ferry is a woman in a red dress, who reappears several times along the way, looking at Hat with, what? Interest? Encouragement? Portent? The rest of the story is Hat’s journey, and his mostly-wordless encounters with an assortment of characters along the way. He rescues a dog adrift in a boat and a handsome man dressed all in white stranded by a car that has broken down. He overhears stories, one about a husband who faked his own death with the help of law enforcement, told by the wife, who then took up with his twin brother. Ah, we may think. It’s about dualities! That could explain the reappearances of several characters, including The Damp Man (Stephen Dillane) and a couple who are constantly holding up measuring tape to whatever is around them. Not to mention the bald men in the Citroën, who keep pursuing him. Or are they?

Another story Hat overhears is about an old man stuck in the mud, though it may have been a dream. We hear the classic French children’s song about the ship that never sails. And we see a comically failed suicide attempt by The Damp Man. There is that framed photo of the woman, which has a surprising use near the end of the film, a chess match at a border checkpoint, and a surprisingly dark speech by a local official at a town festival, including a reference to “the abyss of oblivion.” Oh, we may think. It’s about grief! But then there is a whimsical solution to the problem of sauce dripped onto a shirt that is reminiscent of Jacques Tati, whose influence is felt throughout the film, with intricate, Rube Goldberg-like bits of comedy and bursts of pure, delightful absurdity.

Is it about death? Loss? Life? To debate it would be if not unfair, impolite to this gentle story. Much better to just go along for the ride and relish the lush French countryside, the luscious food, the lovely music, and to think of “The Man in the Hat” as in the title of the Baudelaire poem quoted in the film, an “Invitation to Travel.”

Now playing in theaters and available on demand.