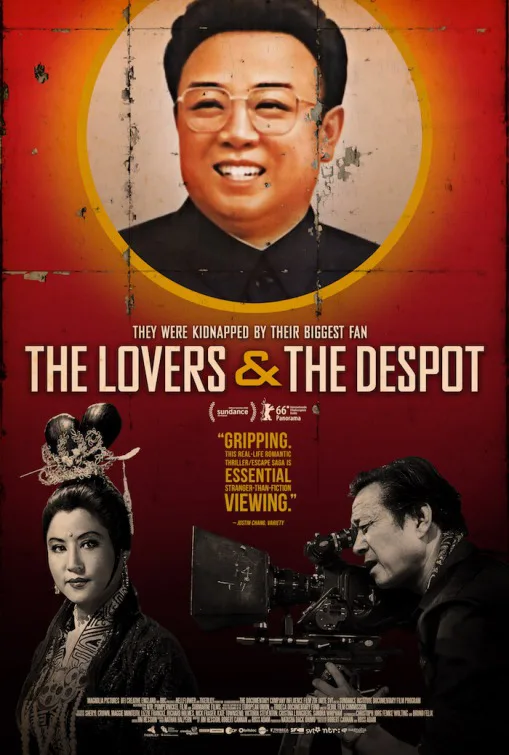

A frustrating missed opportunity, “The Lovers and the Despot” takes a fascinating story about filmmaking, politics, kidnapping and propaganda and gives us almost no insight into the work of its two main characters, a director and his actress wife. Their personalities come through loud and clear, but the artistic and political context in which their amazing story occurred barely gets illuminated—a particular shame given that North and South Korean cinema and politics are subjects than many Americans know almost nothing about, save for the vague oversimplifications they might have overheard on the news on the rare occasions when US media outlets deign to cover that part of the world.

Written and directed by Ross Adam and Robert Cannan, the film marshals a staggering array of material to tell us about one of the strangest stories in international film history. In 1978, North Korean dictator Kim Jong-Il, the titular despot and also a movie buff, decided that North Korean films were boring and resolved to import top talent from the South, which made superior motion pictures. So he kidnapped Choi Eun-hee, wife and sometime leading lady of producer-director Shin Sang-ok, a giant of South Korean cinema in the 1950s and ’60s, and used her as bait to lure the actress’ husband to Hong Kong, where he, too, was kidnapped. The couple was then forcibly relocated to Korea, where the dictator gave Shin nearly unlimited resources to make any kinds of films he wanted as long as they portrayed North Korea, mortal enemy of Shin’s home country, in a favorable light. It’s an astonishing tale that either illustrates the realities of Stockholm Syndrome or the moral cravenness of artists whose values can easily be compromised by a powerful person writing them a fat check.

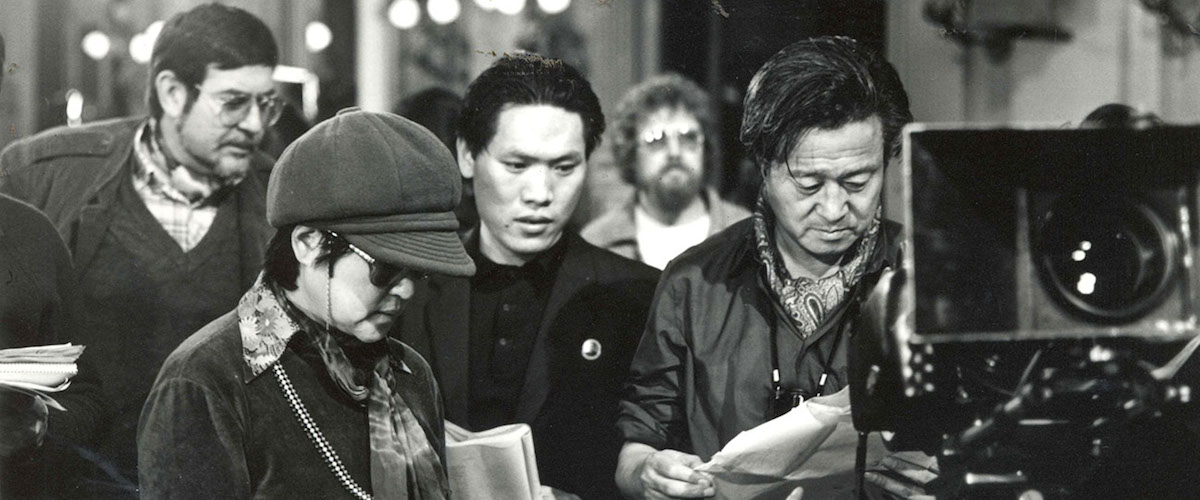

There are many more fascinating details in this story, and the filmmakers flesh out the personal parts of it via newspaper clippings, TV news snippets, abstract footage that might or might not be recreations (the movie is pretty coy about that stuff) and interviews with most of the main participants and many side players; the latter includes a sit-down with a South Korean intelligence agent involved in the case, as well as a conversation with Shin’s brother Choi Kyung-Ok, who describes his sibling as an artist who was aces with actors and camera equipment but a disaster as a businessman. Shin’s company, Shin Films, made over 300 movies but collapsed anyway due to mismanagement. “Shin had zero talent for running a company, zero,” his brother says.

By the time the North Korean government engineered the forced relocation of Shin and Choi, the pair were already kaput as a couple, having divorced after Shin had two children with a younger actress. They spent eight years in North Korea and made eight films there before plotting a daring escape to the west in 1986. Their arrival is captured in TV news footage that opens the movie; the rest of their story is structured as an extended flashback, building toward to their escape in the manner of a heist film or “Argo.”

All of this is fairly well-done, if a bit structurally cliched—too many modern documentaries strive to ape the conventions of fictional genre movies, to the point where they seem slightly embarrassed to be documentaries in the first place—but the attention paid to the emotional mechanics of Choi and Shin’s relationship and the particulars of the escape has the odd effect of Hollywood-izing a story that’s culturally very specific, and that should be able to fascinate on its own terms.

Throughout, footage from Shin’s films is deployed not to give us insight into his artistry or his personal temperament, but to serve as “dramatizations” of real events. For instance, Shin’s brother talks about how creditors would come by and intimidate the production company when they were behind on payments, and we see shots from a Shin film of a lone hero facing down a group of goons. But we don’t know what film the clip is from—the directors never give us so much as a title when they throw a scene onscreen, let alone a sense of what, exactly, we’re looking at, and what it means apart from the odd story of Shin and Choi and Kim Jong-Il.

Fairly or not, the film consistently gives the impression that it’s uninterested in the work of the artists whose personal stories it chronicles, except as a way of illustrating various witnesses’ anecdotes. If this were a ten-minute TV news magazine segment aimed at an audience that had no idea North and South Korea even had film industries, you could probably understand that approach; but the failure to engage with the artistry of these artists makes the story seem less complex and rich than it might’ve been. The personalities are big, the story is striking, but the treatment is unimaginative—except for the editing, which is often clever and beautiful but problematic.

The movie is at its best in throwaway moments, such as the bit where the South Korean intelligence agent talks about Kim Jong-Il’s movie obsession and the documentary cuts to an audio snippet of the dictator complaining about the sorry state of his nation’s cinema: “Why do all of our films have the same ideological plots? There’s nothing new about them. Why are there so many crying scenes? This isn’t a funeral.”