“The Lobster,” a black-hearted flat-affect comedy from Greek director Yorgos Lanthimos, making his English-language debut, presents a dystopian world where being single is a criminal act. A romantic breakup thrusts the “single” into the outer darkness of society. (Like all good satire, “The Lobster” is close enough to reality to disturb the waters.) A single person has 45 days after a breakup to find a new partner, and if the new partner does not materialize, the single person will be turned into an animal. The message is clear: Couples deserve official protection, and the privilege of being left alone by the unnamed State. Single people are accosted in public spaces with demands for appropriate papers. “The Lobster” plays rigorously by its own rules without once telegraphing “Just kidding!” While extremely funny, it is a bitter and ruthless film. Lanthimos plays target practice and his aim is deadly.

In its opening, David (Colin Farrell, in a wonderful performance) listens passively to the off-screen voice of a girlfriend, telling him it’s over. The next scene shows David (dog in tow) checking into a hotel, answering a series of extremely intimate questions about his personal life. Not once does he balk. We don’t understand the rules yet of this world, but David clearly does. (The script was co-written by Lanthimos and Efthymis Filippou, who collaborated before on “Dogtooth” and “Alps“.)

Soon the situation becomes clear: David has come to a facility where single people try to find a mate. No New-Agey retreat, this: the stakes are too high. There are callbacks to films as various as “Defending Your Life,” “Never Let Me Go,” “One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest,” and “Safe,” an institutionalized environment devoted to controlling the chaos of human emotions. There are expeditions in the forest, filmed in luxurious slo-mo, guests hunting each other down with stun guns, winnowing down the ranks. There are demonstrations in a lecture hall about the dangers of being single. (A woman walking by herself is attacked. A woman walking with a man is safe. And etc.) One night there is a dance, and a more joyless event could not be imagined. David befriends a couple of other inmates (no other word for it): a lisping man played by John C. Reilly and a limping man played by Ben Whishaw. Relationship rules require that the lisp-er mate with another lisp-er and the limp-er find another limp-er. It’s a brutal fun-house-mirror of romantic compatibility. If every interaction contains the possibility of monogamy as well as societal-redemption, not to mention avoiding being turned into an animal, then personal connection becomes not only impossible but irrelevant.

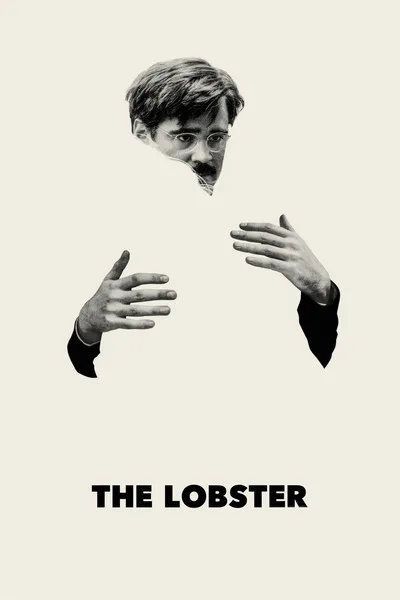

Colin Farrell gives one of his funniest and (strangely enough, considering the humorlessness of the character) charming performances since “In Bruges,” as David. David is baffled, obedient, depressed, defeated. Watch his face as he listens to other people’s “testimonies” at group events. There’s not a hint of self-awareness there. He has zero sense of the absurd. David is a mushy lukewarm pudding of a man. With his mustache and pot belly and nondescript glasses, Farrell is a completely believable everyman.

“The Lobster” is narrated in a monotone by Rachel Weisz, who doesn’t enter the film until some way in. The tone of the narration is key: It is as though Weisz is reading a love poem in botched translation by a third grader. She sounds like a child trying to talk the way she thinks adults talk. The term “deadpan” does not apply. The way people talk in “The Lobster” reveals a complete absence of nuance and subtext. How does one talk about emotions if one has no inner life? It would sound something like Weisz’s voiceover in “The Lobster.” It’s truly bizarre, with a devastating and comedic cumulative effect.

The second half of the film takes place in the forest surrounding the facility, teeming with random recently-human animals as well as a tough band of escaped “Loners,” their fierce leader played by Léa Seydoux. Seydoux gives a charismatic and terrifying performance, reminiscent of the “children of Marx and Coca Cola” in Jean-Luc Godard’s early work, most particularly Veronique, the heartless redheaded revolutionary in “La Chinoise.” The freedom Seydoux represents is heady and deadly as pure oxygen. Her ideal is Kipling’s Cat, who “walked by himself … through the wet Wild Woods, waving his wild tail, and walking by his wild lone.” But in order for freedom like that to be possible, there must be rules. Lots of rules.

Lanthimos is interested, here and in his other films, in the sometimes pathological human need for systems. Why wait for a totalitarian government to institute rules from the top-down when human beings submit to atomization of every aspect of their lives all on their own? If this “need” is wired into the human race, then where does that leave the individual? An individual who doesn’t “go along” becomes a renegade, an outlaw, an unwelcome reminder that the system doesn’t work for everyone.

Lanthimos clocks the fact—and relentlessly lampoons it with surgical precision—that society values couples more it values single people. Valentine’s Day, to a single person, can feel like living in a one-party State bombarding the populace with non-stop propaganda. Every magazine, commercial, movie, daytime talk show is a never-ending parade of relationship advice and aspirational examples of love winning out. Even the dropdown menu choices of “Mr.” “Miss.” and “Mrs.” forces individuals to state their relationship status (and, of course, men get to be “Mr.” whether they’re single or not). It goes without saying that these everyday annoyances do not amount to “oppression,” but they are omnipresent enough that Lanthimos follows them out to their most extreme conclusions. What about “opting out” of all of it? But look out, freedom-seekers: Sociopaths like Léa Seydoux’s character emerge out of power vacuums practically on schedule.

The forest section of “The Lobster” doesn’t work as well as the section in the facility, Seydoux’s performance notwithstanding. Without the walls of the complex pressing in on the characters, the satire floats around in the air, searching for its proper landing-point. Lanthimos’ real target is inside that facility. However, as “The Lobster” marches towards its conclusion, it becomes clear that it intends to go the distance. Lanthimos will not cop out on what his film has unleashed. In a world devoted to happy endings, where platitudes like “the right person is out there waiting for you” or “someday your Prince will come” are parroted as Unquestioned Truths, the film is a welcome breath of freezing cold, poisoned air.