A recent survey indicated that most Americans believe in heaven and hell, and of those who believe, the overwhelming majority expect to find themselves in heaven after they die. Since many of them obviously deserve to go to the other place, if only for owning cars with burglar alarms that go off in the middle of the night, a movie like “Defending Your Life” makes perfect sense.

It is Albert Brooks‘ notion in this film that after death we pass on to a sort of heavenly way station where we are given the opportunity to defend our actions during our most recent lifetime.

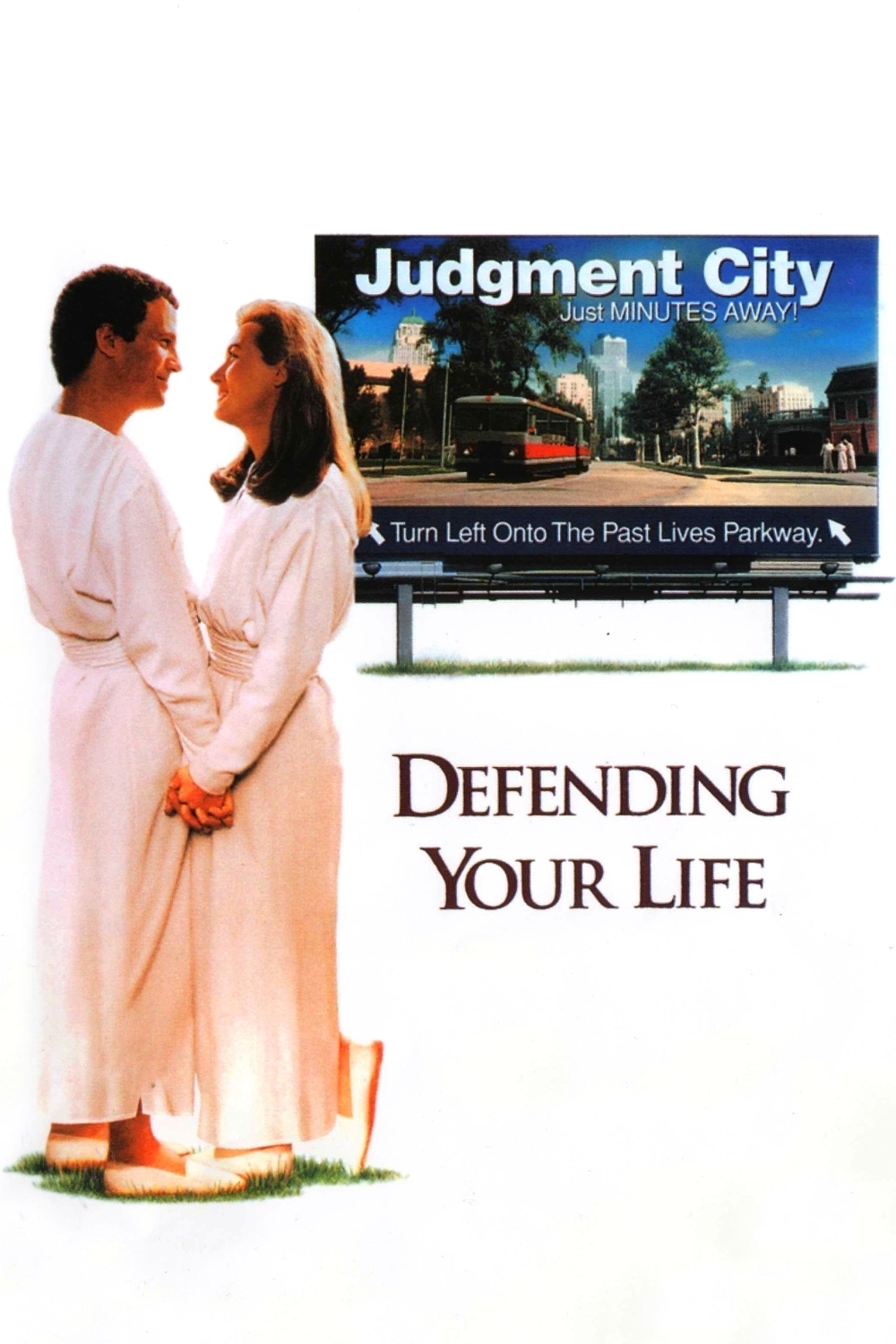

The process is like an American courtroom, with a prosecutor, defense attorney and judge, but the charges against us are never quite spelled out. The basic question seems to be, are we sure we did our best, given our opportunities? In the movie, Brooks plays Dan Miller, a successful exec who takes delivery on a new BMW and plows it into a bus while trying to adjust the CD player. He awakens in a place named Judgment City, which resembles those blandly modern office and hotel complexes around big airports. He’s given a room in a clean but spartan place that looks franchised by Motel 6.

At first Dan is understandably dazed at finding himself dead, but the staff takes good care of him. He’s dressed in a flowing gown, whisked around the property on a bus, and told he can eat all he wants in the cafeteria (where the food is delicious but contains no calories). Then he meets his genial, avuncular defense attorney (Rip Torn), and his hard-edged prosecutor (Lee Grant). It’s time for the courtroom, in which we see flashbacks to Dan’s life as he tries to explain himself.

This is a perfect story notion for Brooks, whose movies always involve his insecurities about himself, his relationships, and his material possessions. (Who can forget the moment in “Lost in America” when he mercilessly blasted his wife for gambling away their nest egg?) But his notion would finally have no place to go if Brooks didn’t add a romantic subplot, in which he falls in love with another sojourner in Judgment City.

She is a sweet, open-faced, serene young woman named Julia and played, of course, by Meryl Streep, who is the only actress capable of providing the character’s Streepian qualities. They fall into like with one another. Dan visits her hotel and is dismayed to discover that she has much better facilities than he does – Four Seasons instead of Motel 6 – and he wonders if maybe your hotel assignment is a clue about how well you lived your past life. But nobody in Judgment City will give him a straight answer to a question like that.

The movie is funny in a warm, fuzzy way, and it has a splendidly satisfactory ending, which is unusual for an Albert Brooks film (his inspiration in his earlier films is bright but seems to wear thin toward the third act). The best thing about the movie, I think, is the notion of Judgment City itself. Doesn’t it make sense that heaven, for each society, would be a place much like the Earth that it knows? We’re still stuck with images of angels playing harps, which worked fine for Renaissance painters. But isn’t our modern world ready for images in which the angels look like Rotarians and CEOs? Stanley Kubrick’s “2001” ended with the astronaut leaving the solar system and finding himself, quite unexpectedly, in a spotless hotel room. The usual explanation for that scene is that a superior race from elsewhere in the universe had constructed this room for him as a place where he would feel at home, while they studied him – much as a zoo throws in some trees for the monkeys. The best joke in “Defending Your Life” is that heaven is run along the lines that would be recommended by a good MBA program.