Combine the subject of religious faith with the cinematic genius of a Robert Bresson and you get a masterpiece like “Diary of a Country Priest,” a film stirring enough to move even staunch skeptics. Unfortunately, the subject is more often approached by lesser talents, resulting in movies like William Riead’s “The Letters,” about the life of Mother Teresa, a drama in which belief is reduced to well-meaning but inert treacle.

To give the film credit where some is due: the look created by cinematographer Jack Green and production designer Aman Vidhate is handsome and commendably expensive looking, even when the setting is the most miserable slum in Calcutta. Whether it was the Vatican or another source that provided the movie’s funding, they got their money’s worth in terms of production value.

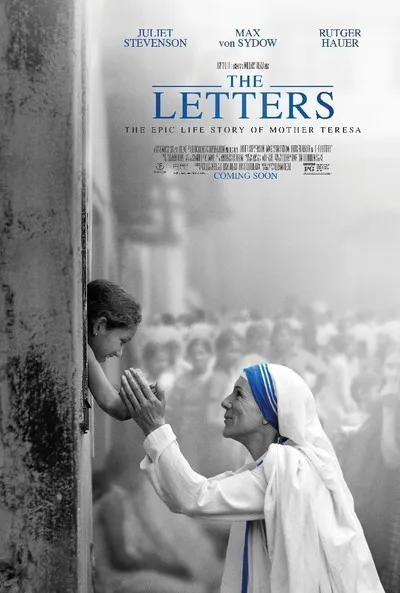

On the level of dramatization, however, the film is almost an object lesson in how not to tell a story like that of Mother Teresa. We start out learning that a woman with a tumor says she has been healed by a photograph of the recently departed nun, which sets Teresa on the fast track to sainthood. Investigating her candidacy for the church, a Vatican priest (Rutger Hauer) visits Father Celeste van Exem (Max Von Sydow), who had been her spiritual advisor for many years, and who narrates her story by using letters she wrote him over several decades.

When his account begins, it’s just after World War II and Sister Theresa (Juliet Stevenson) is living in a Calcutta convent, where she teaches well-to-do Christian girls, and tries to allay their fears regarding the Hindu-Muslim violence that’s erupting due to the approach of India’s independence. Here as after, she’s a model of blandly upbeat piety. The best counsel she has offer her worried charges is, “Try not to worry.”

This section of the film also introduces one of the film’s creakiest devices: having the political context explained by reporters talking with each other. It involves dialogue as awful and straightforward as, “So you think India is going to suffer under the burden of its birth as a modern nation?”

As we learn early on, Teresa is not content with her relatively comfortable situation in the nunnery. After receiving instructions from God (which thankfully we don’t hear) while on a train ride, she proclaims that it’s her mission to try alleviating the misery she sees all around her in Calcutta. But this is easier to proclaim than to do, necessitating a procession of dull, repetitious scenes in which her superiors at the convent resist her campaign even as her appeals to the Vatican stretch on for months.

She eventually succeeds, and is granted permission to keep her vows and affiliation with the convent while being allowed to work in the slum outside it. There, her main challenge is overcoming the suspicions of its Hindu residents. Initially, she’s not out to provide food to the starving or care to the ill. She says she just wants to teach the kids to read, but the slum dwellers think she aims to convert the tykes to Christianity.

Naturally, her purity of intent soon becomes apparent to most of the skeptical Hindus, and her career as a savior of the slums is off and running. Some of her former students even elect to join her, creating consternation among their parents and the convent higher-ups. This is, after all, a caste-bound society and upper-class girls touching the untouchables, even in Jesus’ name, is frowned upon. Soon enough, though, Teresa’s mission is successful enough that she gets the Vatican to let her break free of the convent and establish her own independent Missionaries of Charity, which leads to more conflict with the Hindus but also to the beginnings of her worldwide renown for saintliness.

The film’s biggest problem is indicated by its title. Mother Teresa did leave behind a trove of letters. Though she wanted them burned, a selection that was published posthumously revealed her prolonged spiritual struggles and sense that she was wholly removed from God. A few of these missives are quoted briefly in the movie, but they are completely at odds with what we see on screen, where there’s zero evidence of the protagonist’s internal conflicts or devastating doubts.

Stevenson’s performance as the nun relies on a stooped posture, vaguely Yugoslavian accent and that blandly benign smile. Doubtless she was not given the material for a more complex portrayal. Some films on faith preach only to the converted. This one may leave even some of those unmoved.

A final note: The film’s music is credited to Ciaran Hope, but unless the copy provided for review contained temp tracks, some of it seems to have been lifted directly from Hans Zimmer’s score for “The Thin Red Line.”