Everybody in “The Last Supper” disapproves of that sentiment, and if anybody is going to die, it will indeed have to be Voltaire. The movie is a savage satire about intolerance. By the end, its liberal heroes are arguing about whether they’ve killed and buried 10 or 11 right-wingers in their back garden, but the movie isn’t about left and right, it’s about those on any side who do not understand freedom of speech.

Amazing, really, how many Americans do not support that first freedom. There is a fever abroad in the land to limit our freedom to communicate, and I was not surprised to discover that Sen. James Exon (D-Neb.), the author of the Internet “decency” bill, was unable the other day to answer even the simplest questions about the way it should be implemented. The great thing is to ban things, not define them or understand them.

Strange. We never think to limit our own freedoms. Only other people’s. Consider the five Iowa graduate students in “The Last Supper.” They share a house, eat communal meals and are all proudly left-wing. One day a stranger gives a lift to one of their friends, and they invite him to stay for dinner. The stranger, a truck driver named Zac (Bill Paxton), turns out to be a virulent racist (“Hitler had the right idea …”). He’s also a Desert Storm veteran, and when one of the liberal students makes a wisecrack (“Was that really a war? I thought it was a Republican commercial …”), Zac demonstrates the way true patriots defend their ideas by holding a knife to a student’s throat and breaking an arm. In the struggle that results, Zac is killed.

After the students bury him in the back garden, they get to thinking: “What if you could have killed Hitler, before he was Hitler? Think of the lives you could have saved.” The idea is seductive, and the left-wingers feel heady after their taste of violence. “The conservatives are effective,” one of them complains. “They do things. All we do is buy animal-friendly mascara.” The students plan a series of dinner parties, inviting carefully selected right-wingers. One of the carafes of wine on the table contains arsenic. They listen carefully during the dinner conversation. Their guests include a homophobe (“Homosexuality is the disease; AIDS is the cure …”), a male chauvinist pig (“I doubt most rape is really rape …”), an anti-ecologist, a book-burner and others who eventually find their glass being refreshed from the poisoned carafe. One guy comes in wearing a swastika and is polished off before dinner: “I told him it was Happy Hour. Why waste the food?” This elimination process has a certain perverse appeal, but goes on too long once we’ve grasped the story’s structure. The left-wingers are as intolerant as their guests, but can’t see it because they’re blinded by their own self-righteousness. That’s why it’s a mistake to see “The Last Supper” as being against either political wing: It’s against all those who believe their opinions are so correct that those who disagree should be silenced.

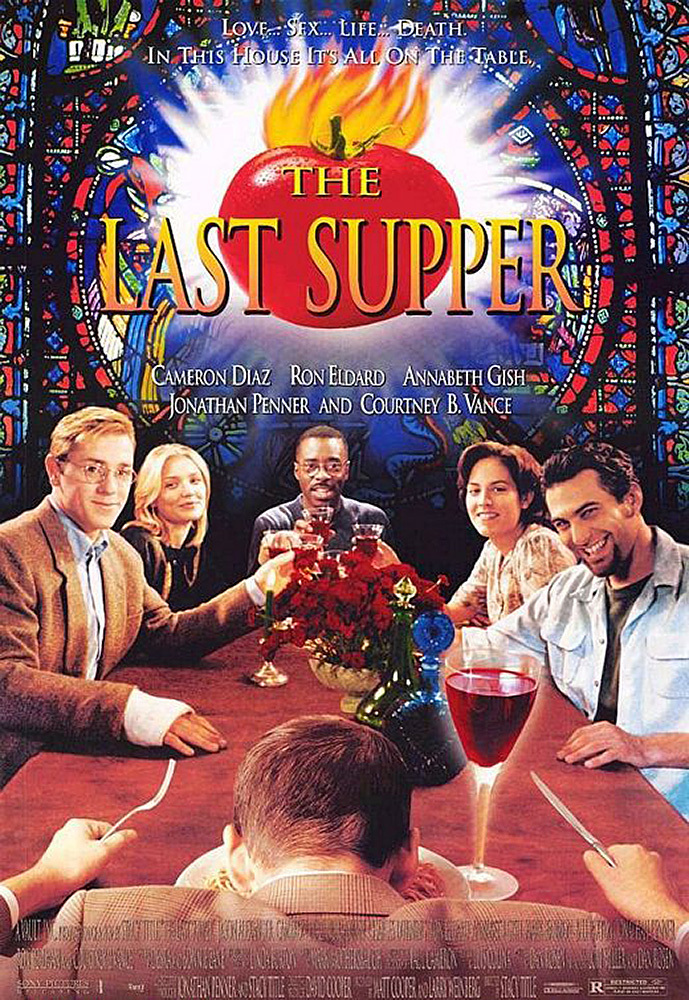

The five students make a lively group. They’re played by Cameron Diaz, Ron Eldard, Annabeth Gish, Jonathan Penner and Courtney B. Vance, all of whom share the crucial skill of seeming smart enough to know better, which is important (if they were stupid, we could forgive them). The guests are played ina series of sharp-tongued cameos by such actors as Charles Durning, Mark Harmon and Jason Alexander. And the film is stolen at the end by Ron Perlman, as a Rush Limbaugh clone who savors his expensive cigar and talks leisurely circles around his antagonists while seeing right through their plot.

If the movie is a little too long and a little too repetitive, it is nevertheless a brave effort in a timid time, a Swiftian attempt to slap us all in the face and get us to admit that our own freedoms depend precisely on those of our neighbors, our opponents and, yes, our enemies. Those who limit another’s freedom of speech create a nation in which freedom can be limited–and what goesaround, comes around. You would think Americans would understand that. Senators,especially.