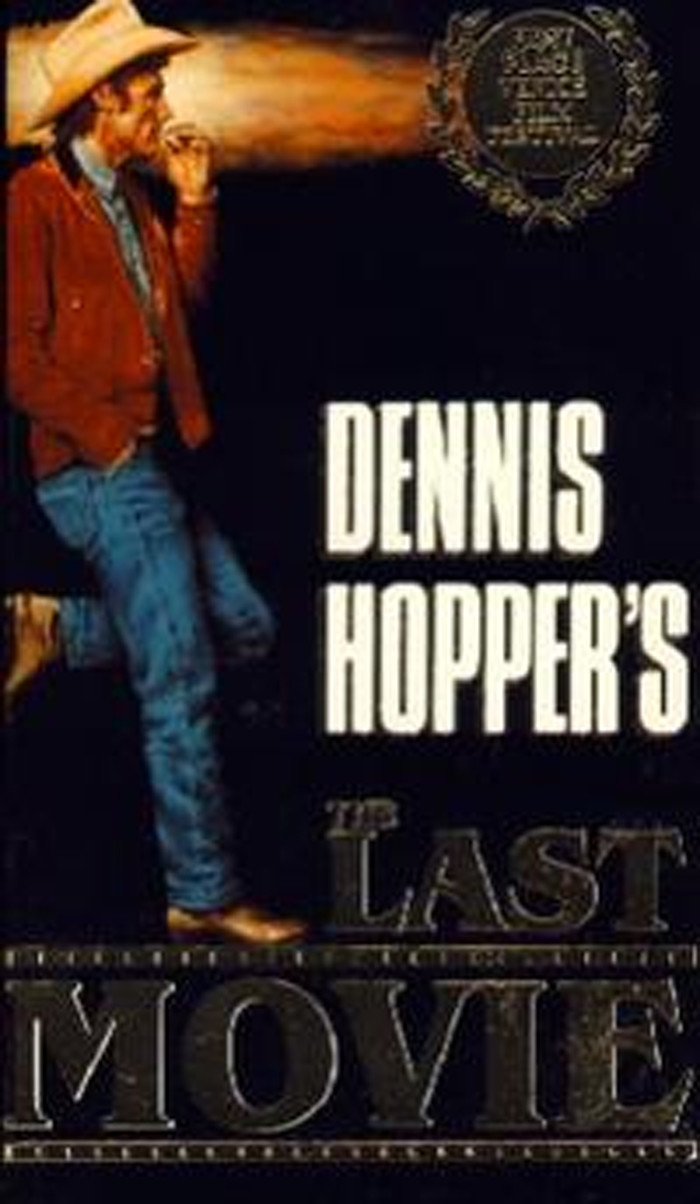

Dennis Hopper’s “The Last Movie” is a wasteland of cinematic wreckage. There are all sorts of things you can say about it, using easy critical words to describe it as undisciplined, incoherent, a structural mess. But mostly it’s just plain pitiful. Hopper hasn’t even been able to cover his tracks; the failure of his intentions is nakedly obvious. Near the movie’s end there’s a pathetic scene in which he sits, half-stoned, dazed, confused, and says the hell with it. It feels like he means it.

In Hollywood, they talk about movies and performances being “saved on the Green Machine.” They mean the editing process, when a skilled editor can take mixed-up footage and somehow give a meaning and structure to it. Movies are such a suggestive art form that a good editor can work around the gaps and chasms in a story line and convince moviegoers that it all somehow fits together.

Based on the evidence in this cut of “The Last Movie,” every possible effort was made to save the project after Hopper finally returned from Peru with his hours of footage. The plan seems to have been to make the movie look like “Easy Rider,” wherever possible, and hope the counter-culture would get behind it. Well, that didn’t work, but I wonder if anything would have worked.

The story line (if you’ll permit me to be linear in the face of the movie’s fragmentation) concerns a Hollywood cowboy extra who stays behind after a B-Western crew has finished filming a potboiler. He shacks up with a girl he’s met, gets involved in a dazed search for gold, passes some time with the local American expatriates, and then he becomes the unwitting star in a “movie” that the local Indians make on the Western sets that were left behind.

It appears from the evidence on the screen that the movie’s events were originally intended to unfold in chronological order. But it didn’t work out that way. Hopper’s gold-mining expedition, for example, is duly announced. But then we get a lyrical sequence of silhouettes against the sunset, trucks driving into the dusk, small figures in a vast landscape, etc., while a suitable song is performed on the sound track. And that is the gold-mining expedition.

After they get back, however, there’s a scene where they try to talk the rich Americans into backing them — and this scene is done in a realistic tone, with lots of dialogue. Then, at the movie’s end, there’s a flashback to a campfire scene on the gold-hunting expedition. This scene, done in the style and mood of the pot-inspired campfire scene in “Easy rider,” has the two prospectors reveal that they learned about gold mining by watching Walter Huston in “The Treasure of the Sierra Madre.”

Fine. The easy stoned absurdity of the scene reminds us of Jack Nicholson and his warnings about flying saucers in “Easy Rider.” But if we watch the scene like cinematic archeologists, we sense the invisible presence of the Green Machine. My notion is that an entire gold-seeking expedition was filmed, and then not used; that the pastoral photography was put in to paper over the hole in the plot, and that the campfire scene was then salvaged and stuck in at the end to give the necessary mood lift before the movie’s downer conclusion.

All of this — the fancy photography, the fragmented editing, the series of expensive performers and high-royalty songs — is just an elaborate rescue attempt. There are also all sorts of guest appearances by Dennis Hopper’s friends, who flew down to the big doings on the Peru location; “The Last Movie” almost becomes the counter-culture’s “Around the World in 80 Days.”

The idea, I guess, is that we’re supposed to understand that if Peter Fonda and John Phillip Law and everybody had a dandy time making the film, and if the movie thumbs its nose at making any sense, and if Hopper throws us off the scene by using title cards that say “scene missing,” and if he leaves in clapboards and puts in a jolly hand-written “The End!” when the movie’s over, why, then, “The Last Movie” must exist on many levels, some of them droll, some significant, some intended as kind of an underground telegram to users.

I dunno. Hip directors can’t always get away with the fast break and the downcourt pass from nowhere; audiences are playing a more defensive game, and for “The Last Movie” they may even have to go into a man-to-man.