What a tortured path “The King and the Mockingbird” has taken to reach theaters in the United States, and what a treat it is for us to be able to experience it now.

The French animated gem—which massively influenced Hayao Miyazaki in the creation of his legendary Studio Ghibli—originally was conceived in the early 1950s, but became tangled in creative differences over which finished cut was the proper one. While it finally came out in France in 1980, it has been mired ever since in rights issues since, which have prevented its release in the U.S.

Now, a digitally restored version arrives in spectacular fashion with its mixture of bold imagery and biting wit.

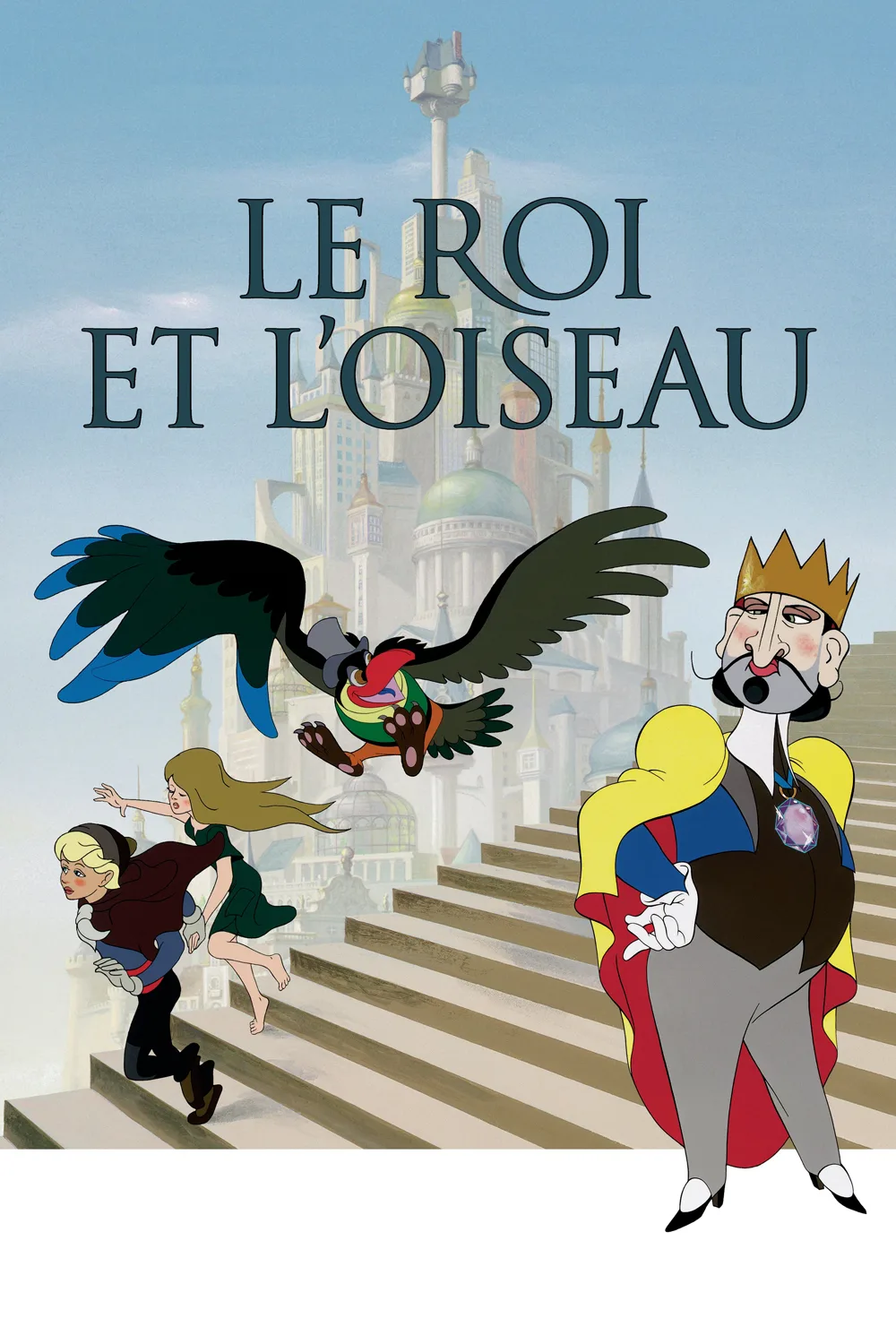

Directed by the late, venerated animator Paul Grimault and written by poet and screenwriter Jacques Prevert, “The King and the Mockingbird” is based on a Hans Christian Andersen story, but its themes of repression and rebellion are timeless. The pompous King Charles (voiced by Pascal Mazzotti), who hates his subjects and is equally hated in return, rules over the amusingly named land of Takicardia. His underlings and hangers-on run around so frantically trying to fulfill his every wish, you can imagine that their hearts are pounding.

This king’s cold and imposing castle stretches 296 stories into the sky and houses everything from a royal pedicurist to a zoo to various types of prisons. The look of the place and the costumes the characters wear are deeply, richly colorful—reminiscent of princess-era Disney classics—but this is no cheeky, self-referential fairy tale turned on its head. “The King and the Mockingbird” may feature talking birds and dancing lions, but it’s a cutting, satirical statement about the perils of power run amok and the terror of totalitarianism.

At the top of the king’s palace lies his secret apartment, which is home to some of his most beloved artwork—chiefly, his portrait of a beautiful and innocent shepherdess (Agnes Viala) with whom he’s desperately in love. What he doesn’t know is that when he’s asleep, the shepherdess and the chimney sweep in the adjacent canvas (Renaud Marx) have been carrying on a sweet and tender affair.

In one of many examples of the film’s playful use of space, the two figures hold hands between their respective frames until the day they find the courage to leap out and explore the outside world together. Grimault depicts the castle as a place that’s dizzying in its boundlessness, from seemingly eternal staircases to secret passageways that magically appear out of nowhere.

Then an incarnation of the king in painting form sends out his loyal (but bumbling) police force to chase after the young lovers and stop them so that he can marry the shepherdess himself. But the couple gets help thwarting him at every turn from the one character in the kingdom who does not worship the monarchy: the brash and trash-talking Mr. Bird (Jean Martin), a brightly-feathered raconteur. Eventually, the bird needs some help of his own once he becomes the captive victim of the king’s tyranny.

“The King and the Mockingbird” accomplishes a great deal wordlessly, and this is especially true as the film’s tone turns bleaker and its look turns darker in oppressive, industrial ways in the third act. Surrealism remains the order of the day, but the mood of the film shifts seamlessly from impish, silly adventures to grotesque and nightmarish suffering.

And then the giant robot arrives.

Just when you think the film couldn’t possibly get any stranger, it does, in beautiful and imaginative ways. The young couple may be headed for their happily-ever-after, but you couldn’t possibly imagine how they’ll get there.