“The Kid,” directed by Vincent D’Onofrio, is, in some ways, a modern spin on an old story, one that has been explored in Hollywood many times before. Based on the real-life tale of the showdown between the famous young outlaw, Billy the Kid, and his arch nemesis, Sheriff Pat Garrett, D’Onofrio’s film transforms many of the classical western tropes into a meditation on the lingering after-effects of domestic violence. The story centers on the coming-of-age journey of Rio, a 14-year-old who shoots his abusive father in an unsuccessful attempt to save his mother from being beaten to death. When Rio and his sister Sara attempt to run, they are accosted by their cruel Uncle Grant, played by Chris Pratt, who threatens to take them both. After playing a series of chipper characters, Pratt makes a believable villain.

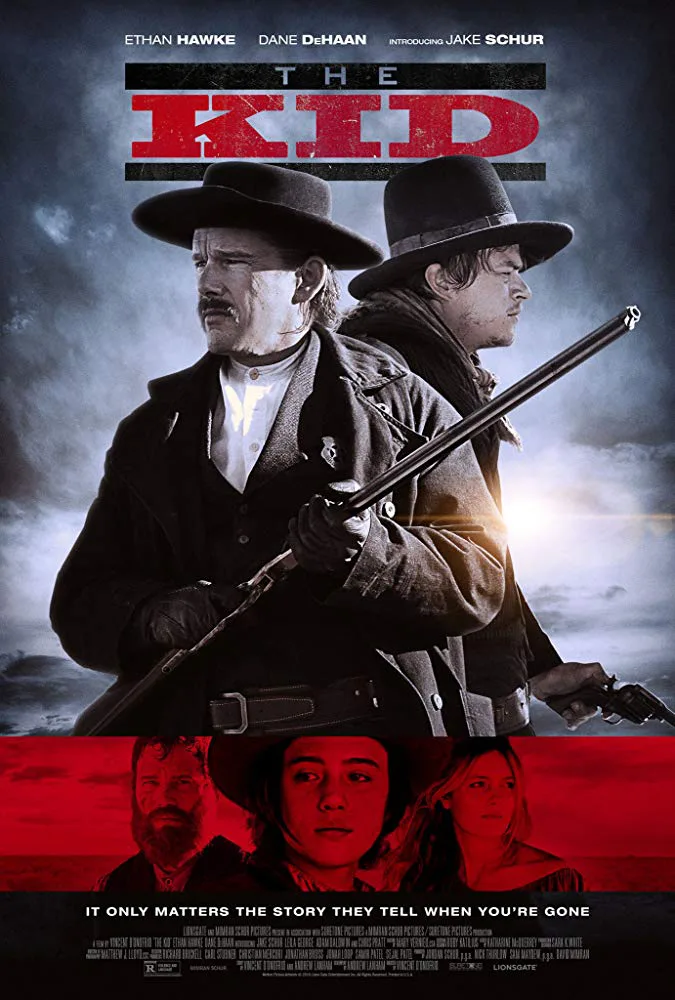

Both Rio and Sara are traumatized from the violence they’ve experienced, and Rio is afraid to run and unsure of who to trust. When he first encounters Billy the Kid, Rio is both frightened and transfixed by Billy’s swagger, a fact that Billy cleverly tries to manipulate to his own ends. Later, when he meets Sheriff Garrett, we see how Rio is ultimately given a choice to either embrace the life of a bandit or pursue a life of virtue and justice. Ethan Hawke’s portrayal of Garrett is earnest and complex, easily the best aspect of the film, and brings to life the story of a man with violent impulses who ultimately chooses to use his instincts to protect, rather than harm.

Rio’s journey towards manhood is explicitly tied to his exposure to and enacting of violence, and, throughout the film, we see how male characters grapple with doing the right thing. In contrast, the female characters throughout “The Kid” aren’t given the same agency. In fact, the same violence that propels moral choice for male protagonists leads female characters to lose themselves. Rio’s mother is beaten to a bloody pulp very early in the film and while we hear her soft body being throttled to death, her character remains a plot device for Rio’s journey, rather than a flesh-and-blood person loved by her children. Likewise, Billy the Kid’s pregnant girlfriend’s main roles are crying when Billy is taken away and begging for him to stay with her. The most developed female character is Rio’s sister, Sara, who is constantly trying to navigate a violent world, which sees her as easy prey. But, though Sara is given the opportunity to enact her own violent revenge, her character arc is not one of triumph, or even character evolution. Instead, her character is tortured for what seems to be the sole purpose of inspiring her brother to make better choices.

This relegation of female characters to the sidelines is depressing for a film released in 2019, especially because it seems entirely possible to have a film looking at masculinity without reducing women to archetypes. In the world of “The Kid,” there are mothers and virgins and girlfriends and whores, all of whom seem to exist entirely in relation to the men they watch fearfully from the sidelines. I know that a number of viewers will attempt to excuse these choices, saying that they are simply meant to be commentary on the roles that women were afforded in the Wild West, but I think it’s also very possible not to dehumanize female characters even when depicting an inherently sexist world. The men in “The Kid” may spend a lot of time beating and killing, but they also seem to have plenty of time to brood, ruminate, and wax on philosophically about their relationship to the world. Why not give the female characters a moment of self-reflection, of recognition that the female experience also includes making moral choices?

The decision to flatten female characters into mere archetypes is an odd choice for a film that is clearly invested in considering the nature of domestic violence, which disproportionately impacts women, both in the real world, as well as the world of “The Kid.” While the film makes a number of attempts to probe more deeply into the pain that undercuts cruelty, these explorations never go very far beneath the surface, nor do they shed new light on the ways that a legacy of violence leaves its fingerprints everywhere. By the end of the film, we don’t really gain any new moral clarity about what it means to confront a world where might makes right, and we are left with the discomforting idea that the only thing ultimately protecting women from violence is a good man with a gun.