“The January Man” is worth study as a film that fails to find its tone. It’s all over the map. It wants to be zany but violent, satirical but slapstick, romantic but cynical. It wants some of its actors to rant and rave like amateur tragedians, and others to reach for subtle nuances. And it wants all of these things to happen at the same time.

Sometimes they do. One of the peculiarities of the film is that nice little touches sometimes occur in the middle of scenes so bad you want to groan. This is not the sort of movie that inspires books about how it was made, but I imagine a good book – and even a good movie – could be based on whatever in the world they thought they were doing when they made “The January Man.” The key is perhaps in the screenplay credit: John Patrick Shanley.

This is the man who wrote “Moonstruck,” a film that aspired to be comic and touching at the same time, and succeeded. No doubt he had “The January Man” squirreled away in the back of a drawer and dusted if off when he got his Oscar. It serves as evidence that he didn’t write great screenplays to begin with, but worked his way up to them by many stages, of which “The January Man” must have been a very, very early one.

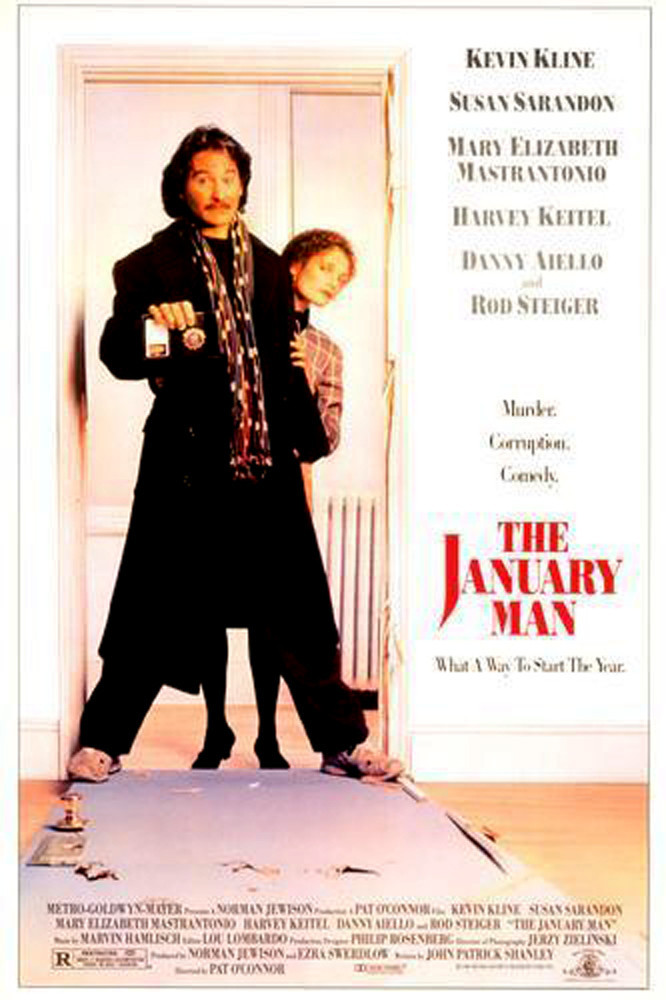

The film involves the search for a serial killer who is terrorizing Manhattan. The city’s mayor (Rod Steiger, foaming at the mouth) demands that the killings stop. So the mayor’s chief assistant (Harvey Keitel) calls on his brother (Kevin Kline), who was a brilliant but nonconformist cop until he got kicked off the force and became a fireman instead. Kline agrees to return to the force and handle the case, but only in return for a dinner date with Keitel’s wife (Susan Sarandon), who Kline has always been in love with – although before long that changes, when he sets eyes on the mayor’s daughter (Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio).

Got that? But pause for a moment and contemplate those elements.

How in a thousand years was this casting ever decided upon? Who believed Rod Steiger and Harvey Keitel belonged in the same scenes, as associates? Who directed Steiger to play the role at a manic pitch of screaming hyperbole, while Keitel remained his usual introverted, tortured self? As for Kevin Kline – first seen rescuing a baby from a burning building – he seems to have based his performance directly on his stage experience in “The Pirates of Penzance.” And Sarandon somehow exists in the middle of this as a moody, complex romantic. Nothing fits. Every role seems to have been faxed in from a different movie, and the actors are on such various planes of emotional intensity that sometimes you can catch them, right there on the screen, looking at each other in bewilderment.

The details of the thriller plot are a caution. After Kline amasses details on the killer, he feeds them into a computer and determines that the “January Man” of the title kills every month on a date that either is, or is not, a square root (surely I can be forgiven for getting this detail confused). Also, he always strikes in high-rises, and Kline is able to predict the date of his next crime, as well as the floor it will occur on, and the exact window it will occur behind. (The theory does not explain how Kline knows which of a building’s four walls to count the windows on, but never mind – no theory is perfect.) As the movie marches toward its showdown with the killer, there is romantic intrigue involving Kline’s passion for Sarandon and love for Mastrantonio. There is a subplot involving the blustering police chief (Danny Aiello). Steiger has a scene so overacted it must be seen to be believed. Keitel has a scene so unactable he seems in actual physical pain as he tries to survive inside of it. And the climax, when it comes, involves Kline and the killer chasing each other down so many flights of stairs that maybe it’s supposed to be a joke.

See this movie, if you must. Then see “Moonstruck,” a film in which disparate parts do indeed work together. “The January Man” serves as a case study of all the ways in which “Moonstruck” could have gone wrong. It also finds a few additional ways to go wrong all on its own.