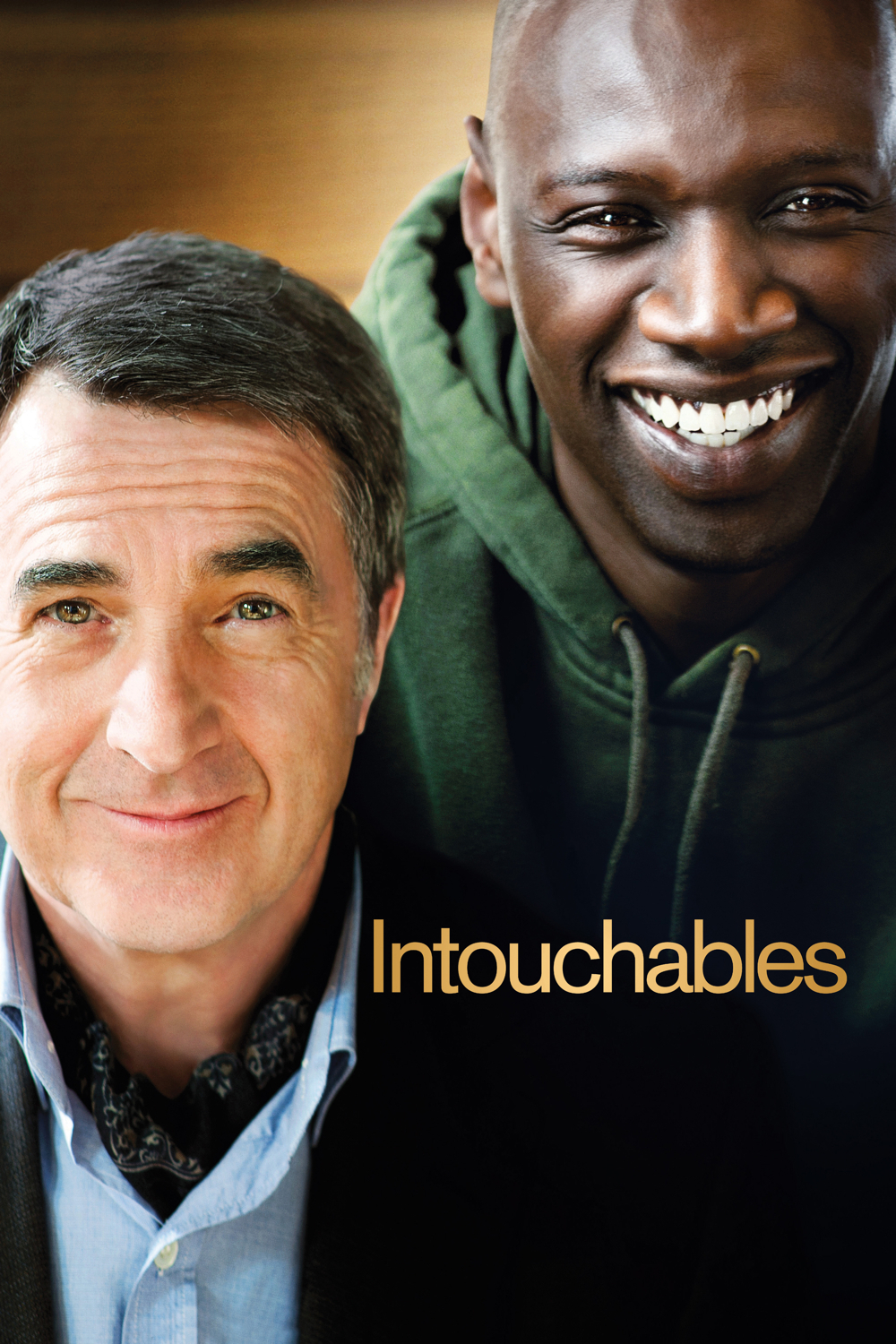

It might help to think of “The Intouchables” as a French spinoff of “Driving Miss Daisy,” retitled “Pushing Monsieur Philippe.” A stuffy rich employer finds his life enriched by a wise black man from the Paris ghettos and takes lessons in funky music and the joys of marijuana. This is a story that has been told time and again in the movies, and sometimes the performances overcome the condescension of the formula.

The film was an enormous box-office hit in France, and indeed, it is easy to enjoy. Philippe (Francois Cluzet) is a millionaire who was paralyzed from the neck down in a para-gliding accident. Driss (Omar Sy) is a man out on parole for robbery, who applies for the job of Philippe’s caregiver only so he can be rejected and get a signature on his application for unemployment benefits. As Philippe interviews one boring job applicant after another, we begin to understand that he needs not only physical help but someone to cheer him up. Driss’ cheeky irreverence is refreshing, and Philippe astonishes him and his own household staff by offering him the job.

The movie tells the story of a growing relationship between these two likable men, based on Driss’ confidence that Philippe will improve if he escapes his stuck-up lifestyle and samples the greater freedoms of an immigrant from Africa. There may be a certain truth in this, but the education of Philippe proceeds in a series of essentially insulting cliches. Driss, you see, has rhythm and soul, and if only Philippe can absorb some of that, he’ll be a happier man. He’ll still be a French millionaire surrounded by a protective staff, he’ll still be paralyzed, but he’ll be happier. How many times have we seen the scene where an uptight square inhales pot for the first time and a smile slowly spreads across his face?

“The Intouchables” has an element of truth that it never quite recognizes. The role of a good caregiver is hardly limited to lifting, bathing, grooming, dressing, pushing and supplying medicines. The patient is faced with a reality he finds difficult to accept: he has been deprived of all he once took for granted, such as the simple ability to walk across a room. A caregiver can’t provide that, but he can provide something more valuable, companionship. Philippe’s wife is dead, his teenage daughter is a snotty brat, and his staff is preoccupied by their salaries and status. Driss comes from a different world.

The success of the film, despite its problems, grows directly from its casting. Francois Cluzet, who acts only with his face and voice, communicates great feeling. Omar Sy is enormously friendly and upbeat. He reminded me of the African immigrant played by Souleymane Sy Savane in Ramin Bahrani’s “Goodbye Solo” — a film that avoided the traps that “The Intouchables” falls into.

The appeal of a film like this, and it is perfectly legitimate, is that when we begin to feel affection for the characters, what makes them happy makes us happy. Caught up in the flow of events, we allow many assumptions to pass unchallenged. The writer-directors, Olivier Nakache and Eric Toledano, are cheerfully willing to go for broad gags, and their style is ingratiating. But at the end, by looking through the foreground details, what we’re being given is a simplistic reduction of racial stereotypes.

That was also true of “Driving Miss Daisy,” but it was a period picture set in the South in the late 1940s, with older characters who had been shaped by their times. There was a plausibility there. “The Intouchables” is more of a soothing fantasy.