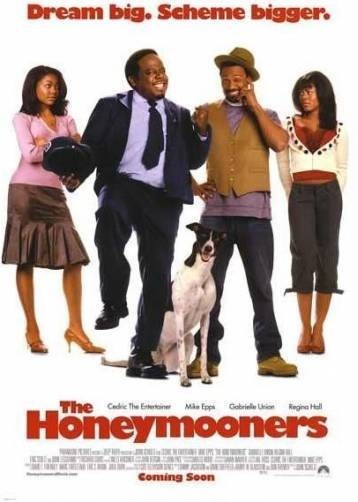

“The Honeymooners” is a surprise and a delight, a movie that escapes the fate of weary TV retreads and creates characters that remember the originals, yes, but also stand on their own. Playing Ralph Kramden and Ed Norton, Cedric the Entertainer and Mike Epps don’t even try to imitate Jackie Gleason and Art Carney; they borrow a few notes, just to show us they’ve seen the program, and build from there. And Gabrielle Union and Regina Hall, as Alice and Trixie, flower as the two long-suffering wives, who in this version get more story time and do not ever, even once, get offered a one-way ticket to the moon. Instead, Ralph even sweetly promises Alice he will “take her to the moon,” although to be sure that’s when he proposes marriage.

The externals of the movie resemble the broad outlines of the TV classic. The Kramdens live downstairs, the Nortons live upstairs; Ralph drives a bus, Ed is proud of his command of the sewer system’s scenic routes. Ralph is a dreamer who falls for one get-rich-quick scheme after another, and the closet is filled with his failed dreams: the Pet Cactus, the Y2K Survival Kit. His wife, Alice, is the realist. All she wanted when she got married was to live in a home of their own. They’re still renting.

Cedric is funny in the role, yes, but he’s also sweet. He understands the underlying goodness and pathos of Ralph Kramden, who is all bluff. Epps makes Norton into a sidekick like Sancho Panza, who realizes his friend is nutty but can’t bear to see him lose his illusions.

The plot: Alice and Trixie, who work as waitresses at a diner, meet a sweet little old lady who wants to sell her duplex at a reasonable price. They’re up against a wily real estate king (Eric Stoltz) who wants to turn the whole block into condos, but if they can come up with a $20,000 down payment, the house is theirs. That means $10,000 from the Kramdens, who have $5,000 in the bank; Alice thinks maybe she can borrow the rest from her mother (Carol Woods), a fearsome force of nature who served in Vietnam, was a Golden Gloves champ and despises her son-in-law (her advice to Ralph on eating his dinner: “When you get to the plate, stop.”).

There is a problem with Alice’s financial plan. The problem is Ralph has spent all the money on a series of failed dreams. Desperate to raise cash, Ralph and Ed try hip-hop dancing in the park, at which they are very bad, and begging as blind men, at which they are worse. Then they find a greyhound dog in a trash bin and decide to race it at the dog track.

Enter John Leguizamo as Dodge, a “trainer” recommended by the track’s shady owner (Jon Polito). Leguizamo is optimistic (“I started with nothing and still have most of it left”) and fancies himself a Dog Whisperer, but Izzy the dog doesn’t seem to understand the principle behind racing, which is that he has to leave the gate and run around the track. Ralph, however, believes in the “homeless dumpster dog,” and in a big scene describes him as “a survivor … like Seabiscuit, Rocky and Destiny’s Child.”

All of this is handled by the director John Schultz (“Like Mike“) with an easygoing confidence in the material. There’s nothing frantic about the performances, nothing forced about the plot; the emphasis is on Ralph’s underlying motive, which is to prove to Alice that he is not invariably a failure and can buy her a house one way or another. That was the secret of Gleason’s “Honeymooners” — Ralph lost his temper and ranted and raved, but he had a good heart, and Alice knew it.

The supporting performances bring the movie one comic boost after another. Leguizamo’s con man dog trainer is an invention in flim-flammery, Polito’s track owner is an opportunist, Stoltz finds just the right slick charm as the real estate sharpie and Woods is the mother-in-law Ralph Kramden deserves for his sins. Hall and Union spend a lot of their scenes with each other while the boys are out getting in trouble. They provide the engine that drives the movie’s emotions: They want that house, they have a deadline to meet, and Ralph grows increasingly desperate because he doesn’t want to let Alice down yet again.

I was afraid Cedric the Entertainer and Mike Epps would try to imitate Gleason and Carney. Not at all. What they do is work a subtle tribute to the earlier actors into new inventions of their own. Cedric has that way of moving his neck around inside his collar that reminds us of Gleason, and the slow burn, and the wistful enthusiasm as he outlines plans that even he knows are doomed. Epps has the hat always hanging on at an angle, the pride in the sewer system, the willingness to go along with his goofy pal. And the movie’s story actually does work as a story and not simply as a wheezy Hollywood formula. Sometimes you walk into a movie with quiet dread and walk out with quiet delight.