“Millions of store-bought bullets are now being smuggled into Mexico,” an on-screen title, one of several, explains at the beginning of this action thriller. “The Hollow Point” looks into some dead-end lives in the Western United States, lives turned inside-out by greed, the promise of big money for a transaction that, seen from a particular angle, can look attractively dangerous.

Believe it or not, and I don’t blame you if you don’t believe it but I feel bad for you if you spend money to find out, I’m already making this movie sound way more attractive and engrossing than it actually is. Its competent lensing of various sun-baked locales notwithstanding—the movie is set in Los Reyes County, Arizona, but was shot in and around Utah’s deserts—“The Hollow Point” is such a shameless and indifferent recycling of Nihilistic Crime In The New American West clichés that it feels like it was crafted by committee. A really lazy committee.

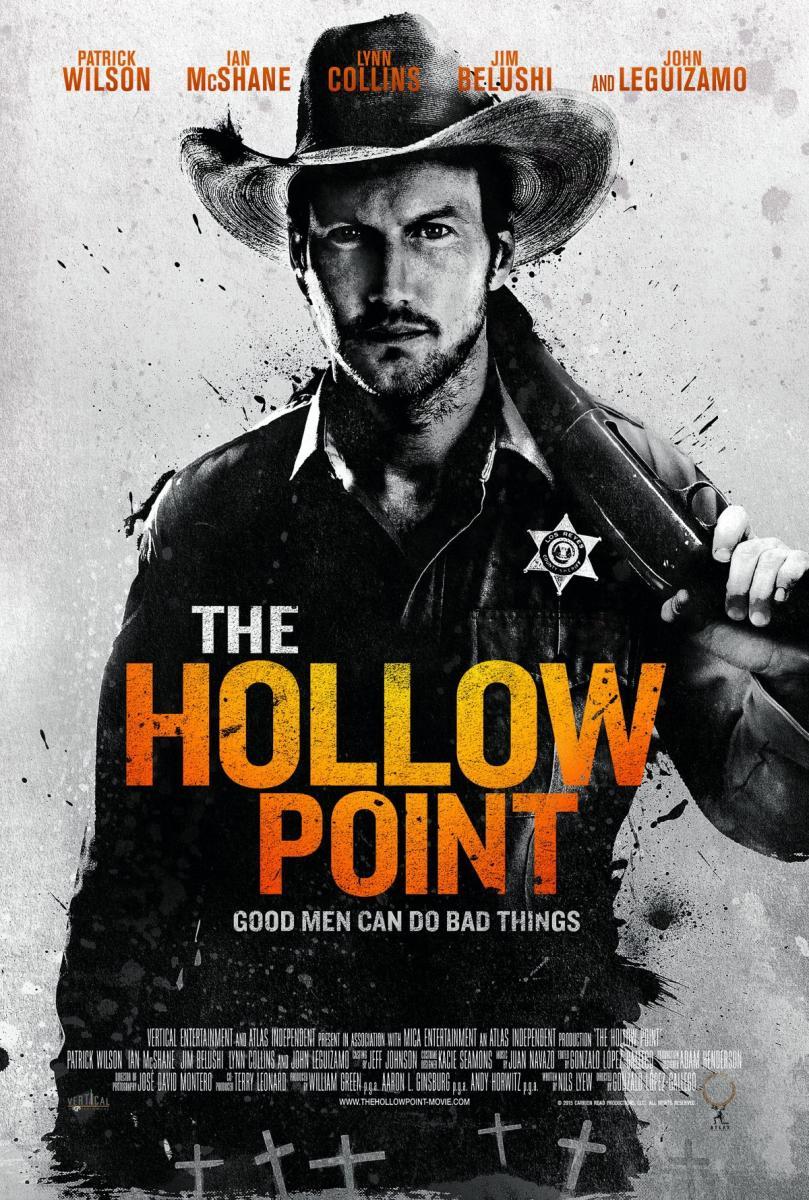

Directed by Gonzalo López-Gallego from a script by Nils Lyew, “The Hollow Point” opens, after the smuggling-ammo texts, with a standard “where’s my money” standoff at a garage in the middle of arid, dusty nowhere, complete with familiar threats such as “If Clive isn’t here in fifteen minutes, soon enough, I’ll be talking to a dead man.” While real-life criminals are not known for speaking in sentences meant to trigger suspense, it’s also a fallacy to say that a crime thriller in which criminals speak realistically just wouldn’t work; one need only read the early work of the crime writer George V. Higgins to understand that. But it’s easier to recycle genre clichés, and Patrick Wilson and Ian McShane are among the good actors called upon to spout them. Wilson plays a new-sheriff-in-town, a veteran cop whose continued existence on the planet seems to be a subject of wonder to many in his community, including his on-again off-again girlfriend Marla (Lynn Collins). Wilson’s Wallace is joining up with McShane’s Leland, an even more veteran veteran who’s used to doing things his own way. The whole county, it seems, has its hand dirty in some way, and the trade in hollow-point bullets is making hands a lot dirtier. “They call them cop killers,” one character says of the ordnance. “Why’s that?” “On account of killing cops.”

To get back to hands, early in the movie Wallace loses one—sliced clean off by a machete wielded by John Leguizamo, who’s still in fighting trim but maybe is getting a little old for these machete-wielding-badass roles. Turns out, of course, that Leguizamo’s character is a man in uniform as well. Completing the circle of morally compromised types is Jim Belushi as a crooked used-car dealer and Karli Hall as a sort of muse to Leguizamo’s character, who posits himself as a kind of avenging angel.

These figures go through the usual grisly paces, betraying each other with unusual persistent regularity for a relatively short film. The movie shows willful ignorance of the immediate consequences of having your hand instantaneously sliced off in an area where there’s no immediate medical care available, that is, you’d likely die of shock rather than stagger to your partner’s house and sit at its side applying pressure to the wound until sunup. But whatever. The dialogue continues in its initial vein: “What is comin’ ain’t no butcher. It’s punishment. You can’t stop that,” goes one scene featuring David Stevens, who by the evidence here would like to make a name for himself as the poor man’s Walton Goggins. Pro-forma shots include the low wide-angle shot of a freshly painted frame house against a bright blue sky, and a telegraphed rack focus during an ostensibly crucial “you’re the guy” moment. There’s literally nothing in this movie that feels like it arose from an impulse to either entertain or create art. You can almost hear the execs in a boardroom making their calculations: take one thriller storyline in the “No Country for Old Men” mode, shoot in Utah, add one cult actor with a rep familiar to viewers of a particular “gritty” TV Western and put him in a similar role, add one competent but not overly costly leading man, bring the picture in for less than X number of dollars and voila, here is a genre picture that will likely yield a not stratospheric but perhaps not insubstantial return on investment. The cynicism, which the actual filmmakers have to try to rise above (and which in this case they fail to do) is almost blood-curdling.