Roger Ebert’s 1967 review of Arthur Penn’s “Bonnie and Clyde” is a landmark in film criticism, a piece of writing that asked readers to engage with a film in terms of what it said about society not in the period in which the film was set but the era in which it was being released. I thought about that film and Roger’s review of it several times during John Lee Hancock’s “The Highwaymen,” which premiered at South by Southwest tonight before a Netflix launch on March 29.

Clearly a counterpoint to some elements of Penn’s film, Hancock’s work seems to be castigating the very concept of even making a movie about monsters like Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow. He returns multiple times to the idea that these murderers became superstars and introduced the film by telling the story of how Gladys Hamer, the widow of one of the men who shot Bonnie and Clyde, sued Warner Bros. over how her husband was portrayed in the first film. The sense that “The Highwaymen” is meant as a “corrective” to Penn’s film is patently ludicrous and requires one to willfully misread Penn’s intentions with that work. And it’s that sense of self-importance that weighs heavily enough on “The Highwaymen” that it sinks under that pressure to be the “real story” to which we should pay attention. Because taken purely as a character study and a platform for a pair of great actors, “The Highwaymen” works. But you kind of have to forget that it’s about Bonnie and Clyde to get there, which makes it a certain kind of ironic misfire.

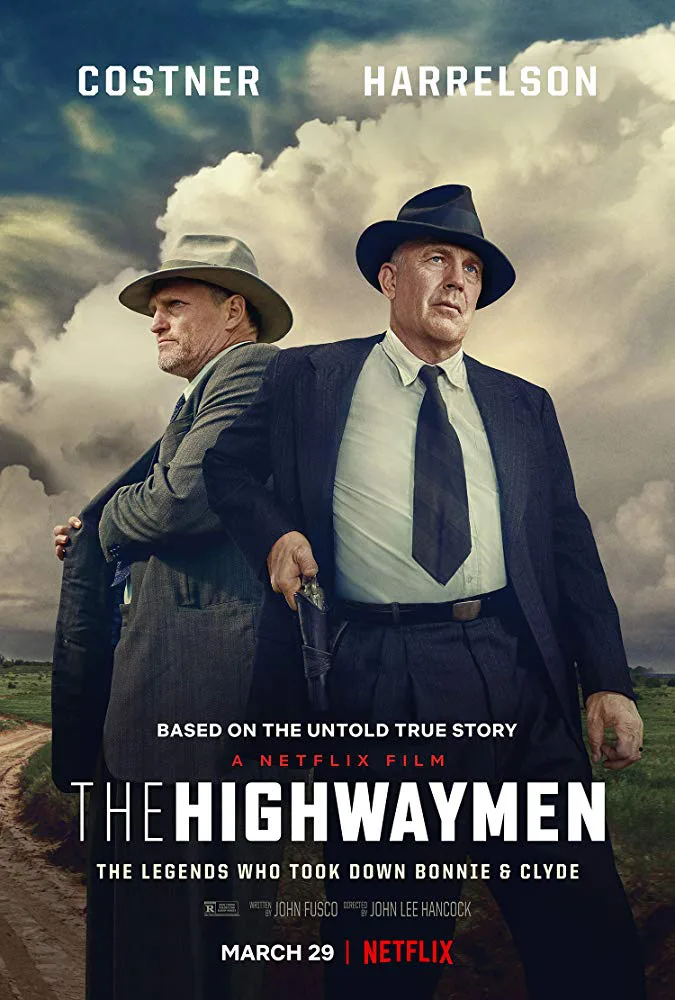

In 1934, Frank Hamer (Kevin Costner) was 50, which is kind of like being 80 in 2019. He was ready to live out his golden years with his wife Gladys (Kim Dickens) and his pet pig when Texas governor Ma Ferguson (Kathy Bates) became convinced that the only way to stop the multi-state rampage of Bonnie and Clyde was to reboot the Rangers. They convinced Hamer to come out of retirement, and he went and recruited an old partner named Maney Gault, himself living on the edge of poverty with his daughter and grandson. The old-fashioned buddy dynamic is clear: Hamer is the leader and Gault is the talker. They set off to stop Bonnie and Clyde, tracking them through the Southeast as their crime spree continues.

Ignoring Penn’s movie (which is doubly hard as we never really see Bonnie and Clyde for most of this film, allowing us to picture Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway in our minds), “The Highwaymen” could have been a solid procedural, a film that offers the factual counterpoint to a myth. There’s value in being reminded that the guys who catch the serial killers never get the same attention as the murderers themselves, but Hancock’s approach is quite simply the wrong one. We get barely any details as to how Hamer and Gault did their jobs. I love a good police procedural, and the details of how we got from a retired Ranger’s doorstep to that ranger being one of the men who pumped dozens of bullets into Bonnie and Clyde could have made for an interesting project, but “The Highwaymen” isn’t that project. Hancock and writer John Fusco are far more interested in long shots of big sky country and alleged commentary on how villains become celebrities than they are with detail. Hamer seems like such a “just the facts, ma’am” kind of guy that it’s doubly depressing that the movie about him can’t mirror that, too obsessed with trying to create its own icons and imagery to feel genuine.

What makes “The Highwaymen” particularly disappointing is that two solid pieces of character work get buried in the filmmaking. I’ve long found Costner to be an underrated actor, and he gets that kind of stolid, unemotional demeanor that impacts a man who has seen more than his fair share of violence. It’s almost too unflashy of a performance but when the film flits off into unearned airs of self-importance, there’s something grounded about it that brings it back to Earth. One could argue that Harrelson could do this kind of Southern charm thing in his sleep, but that doesn’t make it less entertaining. If only both men were challenged by a more complex, layered screenplay because they’re doing enough what they’re given here to prove they would have been up to the challenge.

Ultimately, “The Highwaymen” reminds one that good art can’t be made as a corrective to other art. If “The Highwaymen” had just been old-fashioned entertainment or even a character study, it could have worked, but one feels like they if they looked hard on the miles of road in this film that they would see Hancock holding up signs that say, “This is the true story of Bonnie and Clyde.” Arthur Penn made a movie about ourselves; John Lee Hancock has a movie about itself.

This review was filed from the South by Southwest Film Festival on March 11.