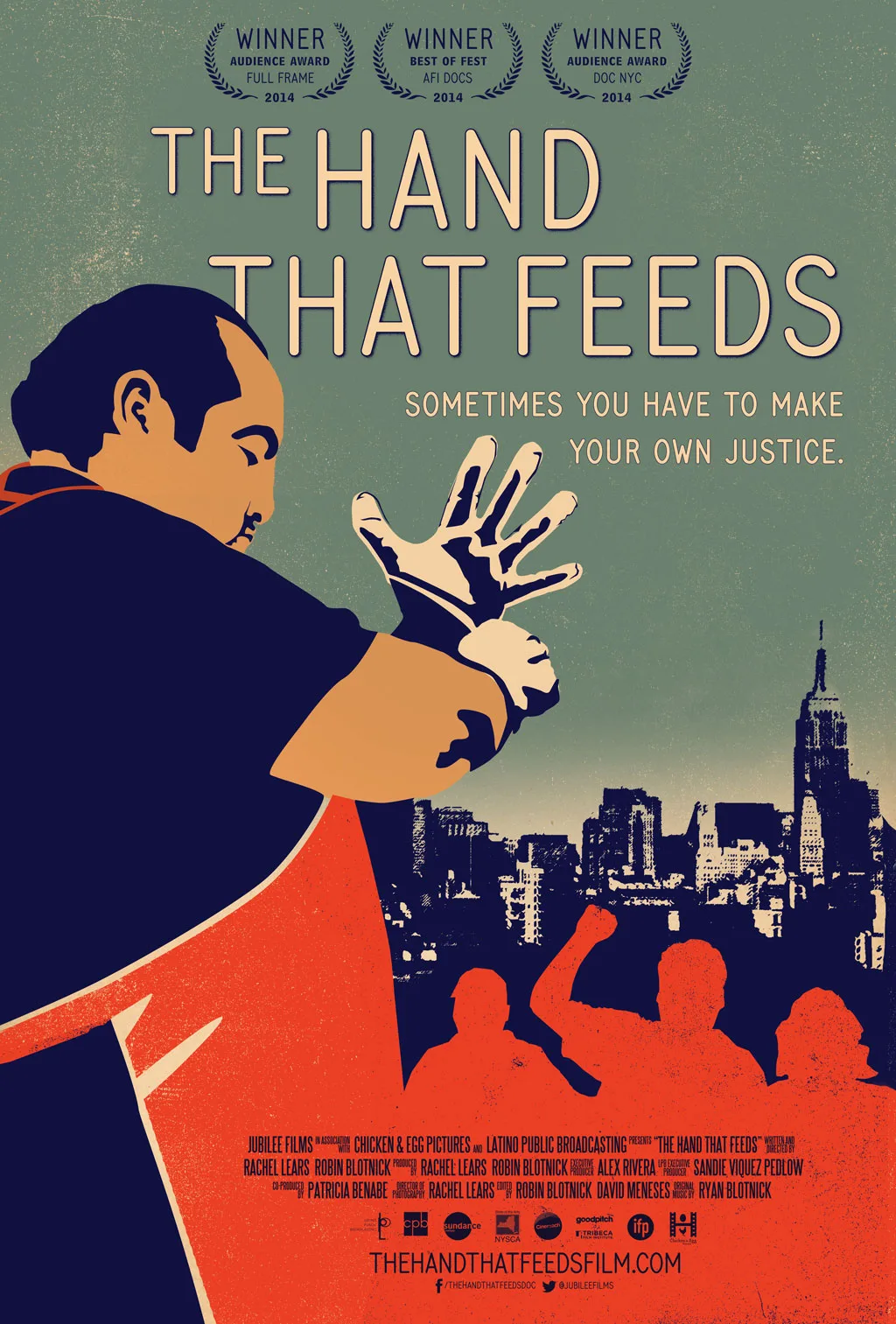

“The Hand That Feeds” tells the type of triumphant real-life tale that Hollywood loves to fictionalize behind the ubiquitous words “based on a true story.” Normally, I’d be against this kind of adaptation, as Robin Blotnick and Rachel Lears’ documentary stands on its own merit. It has a beautiful, low-key approach that earns its cheers and tears without resorting to the manipulative or dramatic tricks of a typical feature film.

And yet, as I watched, I could not help but find myself casting that Hollywood adaptation in my head, a flick filled with up and coming and established Latino actors recreating the tale. There is so little onscreen representation of Latinos at movie theaters that a big budget companion piece to “The Hand that Feeds” would be more welcome than detrimental. Even if Hollywood doesn’t latch on as predicted, we are still graced with this suspenseful and inspiring piece of work.

“The Hand That Feeds” introduces us to the workers of the 63rd Street Hot and Crusty deli in New York City. Many of the workers are undocumented and most work 7 days a week with neither vacation time nor the standard minimum wage. Conditions are less than ideal; we see a cold cuts slicer that is ominously defective and hear stories of managers verbally abusing the workers and cutting their hours if they call out sick. Any complaints are met with the threat of deportation or firing.

“We are undocumented, but that doesn’t mean they have to profit from our hunger,” says Mahoma Lopez, a shy sandwich maker from Mexico City. So, with the help of the Laundry Workers Center, Lopez and several other workers attempt to start a union to force management to provide benefits of some type and a paycheck at or above the minimum wage. Lopez becomes the main focus of “The Hand that Feeds”. We see him come out of his shell as the film progresses, becoming a leading voice of the movement in the process.

“Sometimes the most soft spoken leaders are the most dangerous,” someone says of Lopez.

We also meet Lopez’s wife, Elizabeth, an American citizen of Puerto Rican descent. She and Lopez have a difference of opinion regarding how to handle the unacceptable working conditions at Hot and Crusty, and she tells us her constant fear is that Lopez’s activism will get him attacked or deported. “She thinks all the laws will protect her here,” Lopez says, somewhat bemused. Some of his co-workers agree with her; not everyone in the 63rd Street Hot and Crusty is on the pro-union bandwagon.

Lopez’s mentor at the LWC, Virgilio Aran, speaks of his own prior undocumented status, and how he channeled his anger into helping the disenfranchised organize and fight for their rights. Watching Aran train the group with potential scenarios they might face, I was reminded of old footage of Freedom Riders being prepped with horrific re-enactments of what they might face in the South.

Another constant fixture in “The Hand that Feeds” is Ben Dictor, a member of the LWC’s legal team. He answers the question regarding who can legally unionize: Any employee has the right, and in most cases, the definition of employee covers all types of workers, residential and undocumented. So Hot and Crusty employees like Lopez and his colleague Gonzalo Jiminez are not exempt from the union-making process.

Jiminez provides the first jolt of conflict and suspense when he suddenly decides to drop out of pursuing action against his employer. Dictor tells us that some employers offer up deceptively sweet deals to keep employees from seeking restitution. Lopez angrily assumes this is the case; Jiminez says it isn’t, though both he and Lopez were offered managerial positions in exchange for voting no on the union. His no is one of 8, but the union passes by a margin of 4.

What happens after the union gets created that fuels the remainder of “The Hand that Feeds”. Hot and Crusty responds by accepting the union’s not-unreasonable demands, then closing the successful store a month later. The owners claim they’ve gone bankrupt. Situations both positive and negative arise as a result, and the film does a great job of making us feel the joy and sadness of its subjects as it travels toward its final moments. Lawyers and Occupy Wall Street get involved, and solidarity from other unions co-exists with those who refer to the workers as “commie scum.”

Even though it’s public knowledge, I won’t spoil the outcome for you. You can find out what happens to Lopez and company by watching “The Hand that Feeds”, and you can see other events like this unfolding every day in the news. How you feel about low-income workers vs. employers like Mickey D’s and Wal-Mart may depend on your political bent; this film may come off as uplifting to some and propaganda to others. Regardless, “The Hand That Feeds” does lend an ear to dissenting voices and also to those who parrot that narrative about how all the underprivileged need to do to succeed is work harder. Considering how many hours low-income job employees are working already, and how underpaid they are for that work, this “work harder” idea must require a 30 hour day for folks to simply break even.