This film’s title is a mouthful, no question, yet its plot is spoon-fed simplicity. Never for a moment did I fear that our lead heroine wasn’t destined for the happy ending telegraphed throughout the first act. Sure, stakes are raised on occasion, but never high enough to block the picturesque scenery. As soon as an elderly man vomited on the shoe of a Nazi in German-occupied Guernsey during the film’s opening moments—without consequence, mind you—all sense of palpable danger evaporated from my mind. These aren’t real-life Nazis like the ones who marched through Charlottesville, but rather, the ones who forced the Von Trapps to sing “Edelweiss” in concert, only to let them escape unhindered.

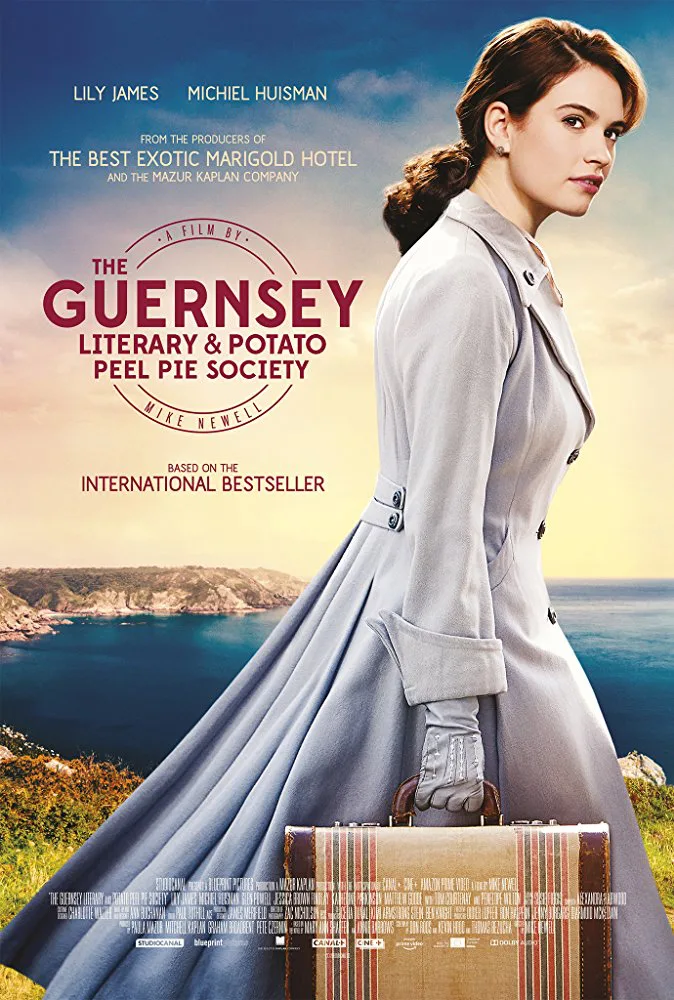

Having said that, I whole-heartedly love “The Sound of Music,” and I have little doubt many viewers will warm to this cozy Netflix Original Movie. “The Guernsey Literary & Potato Peel Pie Society” is being released a mere three weeks after “Mamma Mia! Here We Go Again,” another summer crowd-pleaser tinged with melancholy. Both films are set largely on a gorgeous island, while pivoting between the present day and the vividly remembered past. At the heart of each narrative is a woman whose absence is deeply felt. Whereas Lily James portrayed the young Donna (Meryl Streep’s deceased “Mamma Mia!” character) in flashbacks, here she switches roles by sleuthing through the mysteries left behind by one of Guernsey’s most cherished inhabitants. As Juliet Ashton, an English author who maintains a “You’ve Got Mail”-esque correspondence with Dawsey (Michiel Huisman), the island’s most fetching bachelor, in 1946, James once again proves to be a luminous screen presence. Her fluttering eyelids and megawatt smile single-handedly held my interest in 2015’s pointless “Cinderella” remake, though thankfully in “Guernsey,” Juliet is far more proactive about severing the chains of her imprisonment. Moved by stories of the island’s literary club, which bonded the community amidst the despair of WWII, the writer sets out to meet its members in person, though not before her chauvinistic boyfriend, Mark (Glen Powell), slides an engagement ring on her finger, thereby marking his property before it’s shipped. When Juliet bristles at Mark’s claim that he let her leave, it’s only a matter of time before this love triangle arrives at its expected destination.

For all of its breezy charm, what makes “Guernsey” an often frustrating experience is the fact that the story uncovered by Juliet is exceedingly more interesting than the one she finds herself confined within. When she learns that the club’s rebellious founder, Elizabeth (Jessica Brown Findlay), is no longer present on the island, the author ventures to discover the truth of her disappearance, thus requiring James to spend many scenes asking, “What happened?”, until the reluctant witnesses cave. This process of manufacturing intrigue by withholding soon-to-be-revealed information—summoned up crumb by crumb—is a classic storytelling device, yet it tested my patience in this case, since the dominating narrative is throughly predictable from the get-go.

Time and again, the film consistently deprives us of the good stuff. We only get fleeting glimpses of the club’s spirited readings and debates, which are a joy to watch, especially with veteran talents like Tom Courtenay and Penelope Wilton in the mix. Courtenay’s best moment occurs as he delivers impassioned words directly into the face of a sleeping Nazi attending their meeting. “When respect for other people goes out the window, the gates of hell are surely opened and ignorance is king,” he declares, oddly echoing a famous passage in Walter M. Miller Jr.’s 1959 sci-fi novel, A Canticle for Leibowitz. A few sentences later, Miller notes that those who feed off ignorance fear literacy, “for the written word is another channel of communication that might cause their enemies to become united.”

Over the end credits, we hear the audio from a club meeting where Wilton argues that when it comes to Virginia Woolf, “narrative is not the author’s primary concern.” If only that were true of this screenplay, which displays little interest in any moment of observation not designed to simply move the plot forward. More than any of the romantic entanglements, I was most touched by Juliet’s encounters with Isola (Katherine Parkinson of “The IT Crowd”), the self-described non-beauty of the club, who embraces Wuthering Heights as a distraction from her nonexistent love life. They share a lovely scene in bed, as they talk around certain truths that were branded taboo in their era. Isola admits that she’s still a virgin, while Juliet reveals that her publisher and lifelong friend is gay (he’s played by Matthew Goode with a suaveness worthy of Cary Grant). Less successful is the awkwardly truncated farewell between the pair, as Isola cries, “When you’re gone … ” with such swelling emotion, I half-expected an ABBA number to break out. Juliet’s conviction regarding the importance of issues such as gender equality results in some fist-pumping moments, yet her lines often feel more like statements than dialogue. When she stands up to a maid (who is undoubtedly a member of the same Busybodies Anonymous club run by Mary Wickes in “White Christmas”), Juliet grabs the Bible from her and exclaims, “Here is a book filled with love, and you overlook it for judgment and petty meanness!” These words couldn’t be more on-the-nose, but James delivers them with stirring ire.

Every time Elizabeth materializes onscreen, we are reminded of how much more rewarding the film would’ve been had it foregrounded her story instead. As Nazis marched down the streets of her hometown during the occupation, she walked right up to them screaming, “Shame!” How she managed to later fall for one of the German officers is never adequately explored. Equally timely is the tragedy of Elizabeth’s fate, as deportation results in the splintering of her family. Had Dawsey been clinging to his supposed infatuation with her while finding himself attracted to Juliet, this might’ve blossomed into a melodrama on the order of the club’s iconic selections, but alas, the ghosts of Guernsey do not linger. Not only does the narrative framework provide a reassuring distance from the wartime horrors, the script repeatedly forces characters to spell out things we could’ve easily gathered from a single wordless expression. Once Juliet reads that Dawsey had been found guilty of assault, she looks toward the camera and says out loud, “Dawsey attacked a man?!” It’s the sort of line that exists only for viewers who had neglected to read the text clearly displayed in the previous shot.

In need of no dialogue at all is Wilton, whose withering stare could flatten an entire valley of flower beds. She repeatedly threatens to walk away with the picture, as her character is put relentlessly through the emotional ringer. When Isola questions whether a four-year-old would be able to comprehend the finality of death, Wilton tearfully replies, “I’m older than time and I understand nothing.” This is a line evocative of a tougher film like Christian Duguay’s underrated “A Bag of Marbles,” which shares many themes with “Guernsey,” particularly the value of objects passed through the generations and how families can be formed among strangers during times of profound distress.

The flaws in this film are considerable, yet they aren’t quite enough to torpedo the abundance of good feeling it delivers. Mike Newell is skilled at delighting audiences, and “Guernsey” is the director’s most accomplished feature since his marvelous 2005 installment of the “Harry Potter” franchise. Fans of the bestselling novel upon which it is based will likely eat it up, and though the subject matter could’ve been developed into a more challenging and provocative yarn, this film’s chief aim is escapism. It’s a welcome diversion at a time when the nation’s collective blood-pressure is continuing to climb. My favorite moment in the picture is also the one that, for me, rang the truest. Only after breaking off her engagement is Juliet able to produce her best possible writing, just as the baby’s birth in “Waitress” prompts its heroine to leave her worthless husband for good. In both cases, patriarchy gets a well-deserved pie in the face.