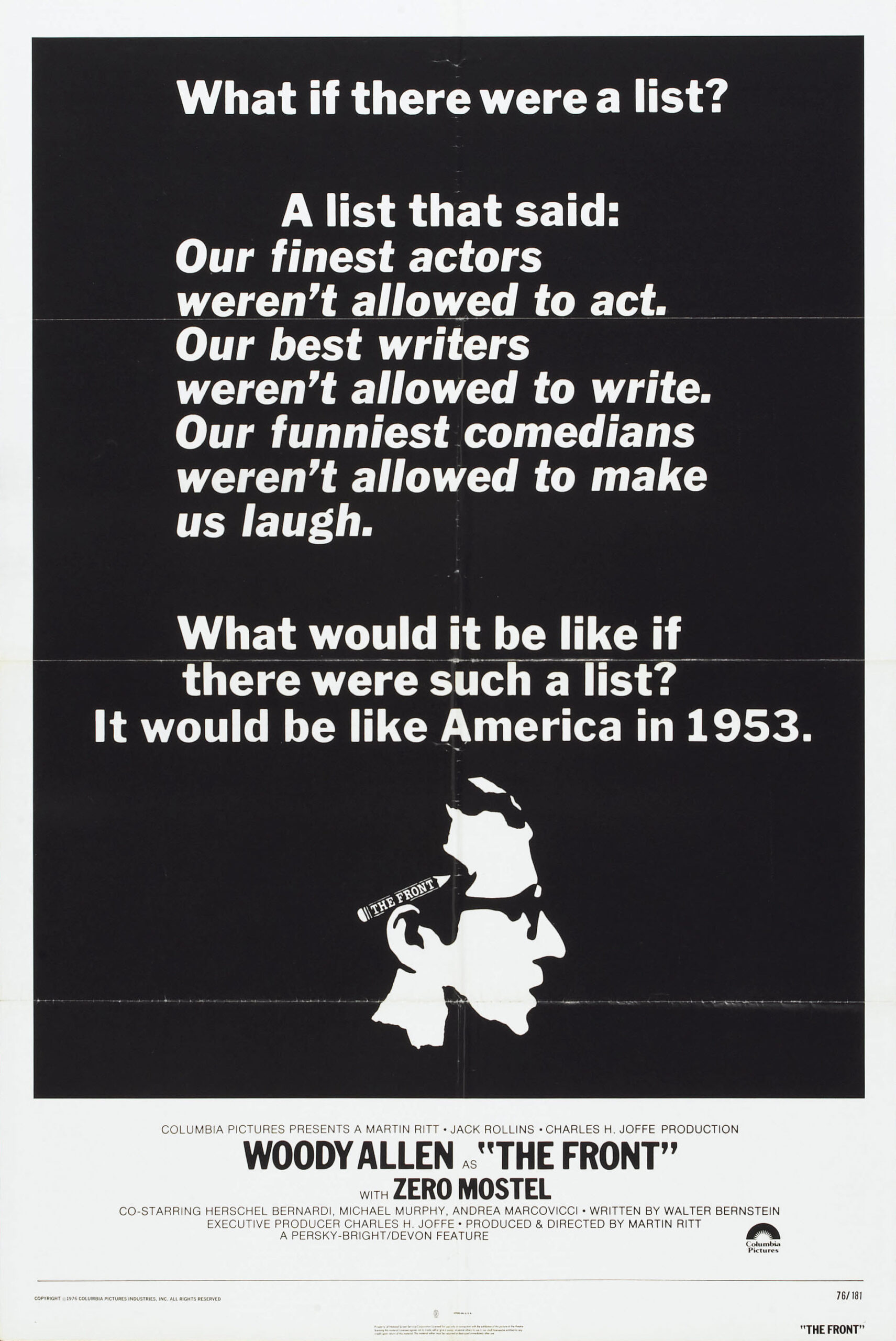

Martin Ritt’s “The Front” is the victim of its own publicity. For months, we’ve been promised this serious film treatment of McCarthyism and the show business blacklists of the early 1950s. We’ve heard about Woody Allen in his first serious role, and about how the film’s director, its author and two of its stars were themselves blacklisted. We expected an indictment of a shameful chapter in American history.

What we get are the adventures of a schlemiel in wonderland. Now those in themselves wouldn’t make a bad movie, and “The Front” has its moments. But they often seem to be moments from a Woody Allen movie — scenes where the insecure Allen character tries to appear competent and win the girl who’s taller than he is, all at once. If “The Front” had simply settled for being that kind of movie, we could relax and enjoy it. But it keeps pushing for a larger statement, and since the issues involved are totally outside the comprehension of the central character, the movie falls apart.

Allen plays a New York delicatessen clerk whose highest ambition, early in the film, seems to be keeping his fingers out of the meat slicer. He’s approached by an old neighborhood buddy with a problem. The buddy is a Communist sympathizer, and has been blacklisted; suddenly it’s impossible for him to sell scripts to television. The buddy makes a proposal: He’ll write the scripts and Woody can front for him, pretending to be the real author.

Woody agrees to the idea, and at that moment, the screenplay takes the wrong turn. Instead of dealing with the blacklist, it deals with Allen. When Woody walks into a studio with a script under his arm, the movie becomes the story of his personal rise and fall. On this level, “The Front” is actually fairly successful — but didn’t Ritt and his writer, Walter Bernstein, see they’d abandoned the theme they chose themselves? Everyone connected with the movie seems to be under the delusion it’s an attack on the blacklist; instead of playing it at a benefit for the American Civil Liberties Union (as they did) they should have held a sneak preview for delicatessen clerks.

The movie makes a central misunderstanding: By casting this particular character as a writer, it immediately becomes a fantasy. We may know that Woody Allen in real life is a writer (not only does he write movies — he even writes for The New Yorker, for chrissakes). We may even suspect that, with the right screenplay, Allen could convincingly play a writer. But his character in “The Front” obviously couldn’t provide the denouement for a laundry list, and that’s so clear to us that we can’t believe the TV professionals don’t spot it. Allen arrives at the studio with a script. He is unable to discuss it, rewrite it, analyze it or, sometimes, even to remember it. Yet, the pretty assistant to the producer (Andrea Marcovicci) falls in love with him because of the deep human content of his writing. You don’t get employed in TV by being that dumb (not in those days, anyway.) The movie becomes a suspenseful game: If Woody gets unmasked, will he lose the girl and have to slice pastrami again? The moral issues involved become an inconvenience; blacklisting is the backdrop for a situation comedy.

In the midst of this extended miscalculation, one element stands out Zero Mostel’s performance as Hecky Green, a blacklisted comic. The script provides him, at least, with a character we can believe in. He’s a blustering, cocky TV top banana who suddenly finds himself unable to get work even in the Catskills. The tragedy implied by this character tells us what we need to know about the blacklist’s effect on people’s lives; the rest of the movie adds almost nothing else.