Alternately eerie, frightening, coy and safe, the “Purge” films seem remain trapped in an intellectual uncanny valley of sorts: too much yet not enough. The series is about the thirst for violence embedded in the American character, and how ritualized and joyous the expression of that tendency has always been. It’s a germ of a concept that seems incendiary and bold on first glance. But in executing it, the series (which now includes a two-season TV drama) makes sure to stay vague enough that American viewers can read each new entry through a generic survival-story lens of “decent people trying to endure terror” and not question their own vision of life too deeply. The Purge-o-verse is about class and exploitation, kinda, and about racism and xenophobia, kinda, and also sorta about American paranoia and bloodthirstiness. But mostly it’s a generic dystopian tale that’s no more or less serious than “The Hunger Games” or “Resident Evil,” just nastier. Bad people take over; civilization fall down, go boom.

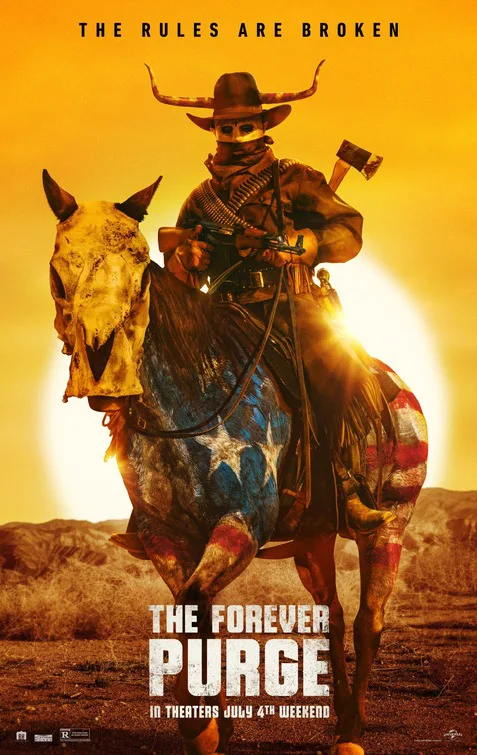

“The Forever Purge,” a continuation and expansion of the franchise, is set near the border separating the United States from Mexico, and centers on Mexican immigrants. They’ve relocated to escape the violence of drug cartels that have hijacked portions of their home country, only to find things are just as bad up North, in a different way. Ana de la Reguera and Tenoch Huerta star as Adela and Juan, a couple who get work in a small Texas town—Juan as a cowboy on a ranch, Adela in a meatpacking plant. To ask why Adela and Juan needed to move to the US to figure out that the Purge-era US is a bad place for people like them is to mark oneself as a spoilsport. Purge nights have been going on for years, and the nation has been resisting irrevocable takeover by a modern Nativist party for just as long. And the country is just generally a bloody cesspool—a place where a significant percentage of citizens are addicted to rage, and want to hurt others because committing violence makes them feel powerful even though, in the greater scheme, they aren’t.

This film is set after the events of 2016’s “The Purge: Election Year,” which saw the The New Founding Fathers of America (NFFA) and their candidate, Minister Edwidge Owens, defeated, and Purge Nights banned. Unfortunately, remnants of the NFFA are still active. They want the Purge reinstated and made continuous so that they can freely exterminate native or naturalized minorities as well as any immigrant who isn’t white. Other militia and gang-type groups want similar indulgences for their own political reasons (there are representatives of a class reductionist leftist group—like a scary cartoon cousin of the DSA—that wants to execute one-percenters and their families). And of course there are garden-variety criminals and psychos who have no beliefs per se, but just want to be able to do their own personal droog rampage whenever they feel like it.

Written and co-produced by series creator James Demonaco, and directed by Mexican-American filmmaker Everardo Gout, this new film (which has been characterized as the “final chapter” in the franchise—a likely story) does go several steps further than earlier entries down the road towards saying something beyond “America is innately violent.” It anchors its brutality in recent political specifics, mostly having to do with former President Donald Trump’s border wall, Trump’s channeling and amplifying of white grievance, and the immigration of Spanish-speaking people to the USA.

But in the end, the film retreats into “we’re all in this together, can’t we get along?” posturing, landing in a centrist-to-conservative mind-space wherein we can all agree that heavily armed and openly bigoted terror groups run by Anglo-Americans are bad, and that wanting to murder rich white bigoted exploiters, while perhaps historically comprehensible, is also bad, in relation to the Ten Commandments anyway, and that once such extremists are dealt with, we can all get back to being decent to each other, which is the True American Way, deep down.

Our heroes find a sympathetic ear in the form of Juan’s employer, ranch owner Caleb Tucker (Will Patton). Tucker is a unicorn: a wealthy but politically liberal Anglo Texan who volunteers, while being terrorized by a white leftist and his goons, that Americans are living on stolen land, and that his tormenters’ refusal to admit that is a sign of their own unexamined privilege. “You got no right to complain about the very system that you’re supporting,” he says. His son and heir apparent, Dylan Tucker (Josh Lucas), is initially presented as a straightforward racist, but the movie later suggests that his attitude (that the races should stick with their own kind, an idea Juan seems amenable to) is at least less horrible than roving white supremacist gangs’ desire to kill anyone who doesn’t look like them. (“Speak English,” they keep ordering brown-skinned people, sometimes while city blocks are on fire.)

The plot eventually leads to a racially mixed bomber-crew-assortment of characters, including Dylan’s pregnant wife Cassie (Cassidy Freeman), running for the Mexican border to escape American violence (an admittedly clever reversal of how this narrative typically works; Canada is also offering Americans asylum for a limited time, as long as they come unarmed). We’re better than this, “The Forever Purge” seems be saying. Are we, though? Native Americans and the descendants of slaves would disagree. But that’s beyond the scope of this review, and apparently not within the purview of Demonaco’s expanded universe of societal collapse and “Children of Men“-style extended tracking shots through carnage on main street.

The end product is a mixed bag. You might appreciate how “The Forever Purge” sharpens things up until it speaks to what happened in the United States under Trump (the “let’s just say all the hateful stuff loud and proud” aspect, primarily), while at the same time noticing that once again, as always, the franchise is stirring free-floating anxiety and rage into a stewpot and dipping into it every few minutes to serve up a tasty bit of violence, but never focusing its vision to the point where it stings in the way that, say, George Romero’s zombie films did. At least there are a few grimly poetic flourishes, as when a neo-Nazi prisoner chained in the back of a police wagon listens to the array of guns going off during their drive and identifies each make and caliber by sound alone. “Homegrown music from the heartland,” he says, leering in ecstasy. “That is American music, motherfucker!”

The performances are better than the material deserves—particularly those of De la Reguera and Huerta, whose reactive closeups have a silent-movie expressiveness; and Lucas, who once again proves that he’s willing to play deeply unlikable characters without signaling that he’s a nice guy offscreen. The final third of the movie, which introduces nasty Nazis and Nazi-adjacent baddies only to swiftly kill them off, feels like a videogame with actors.

Now playing in theaters.