There’s something I’ve noticed in a couple indie pictures lately, and I’m wondering if it’s a trick that competent editors suggest to give a little oomph to movies. I’ll call it The Unnecessary In Medias Res. The movie will open on a scene of relative zippiness or suspense, ending on what’s meant to be a suggestive indeterminate note. Then a title will come on screen: “24 Hours Before,” “Two Weeks Ago,” “Three Months Ago,” or some such thing. The film will then go on, telling its narrative, and eventually it will catch up with the scene that began it. What will follow will make sense not just in the context of the larger plot but satisfy the viewer as to why the scene was put at the beginning of the movie, out of sequence, in the first place. BUT, in less accomplished movies, the viewer is left asking, why’d all this have to be in flashback?

This year I saw the device used with almost comic blatancy in the worthless thriller “Misconduct.” And it pops up again here in “The Family Fang,” and proves completely unnecessary. The movie opens with a sequence made to look as if it was shot on video tape, a documentary of a little kid holding up a bank in the 1970s. There’s a twist, and it has to do with the very nature of the family cited in the title, and that twist is the first and really only effective bit of manipulation in the entire film. The “archive” footage would have made a pretty compelling opening to the movie in and of itself. Instead, the movie then cuts to a depressed-looking Nicole Kidman in a dark room watching the footage on television, popping out the cassette, and leaving the room, as the camera pans to a corkboard festooned with maps and news articles about the disappearance of a pair of once-prominent conceptual and performance artists. And then … flashback time.

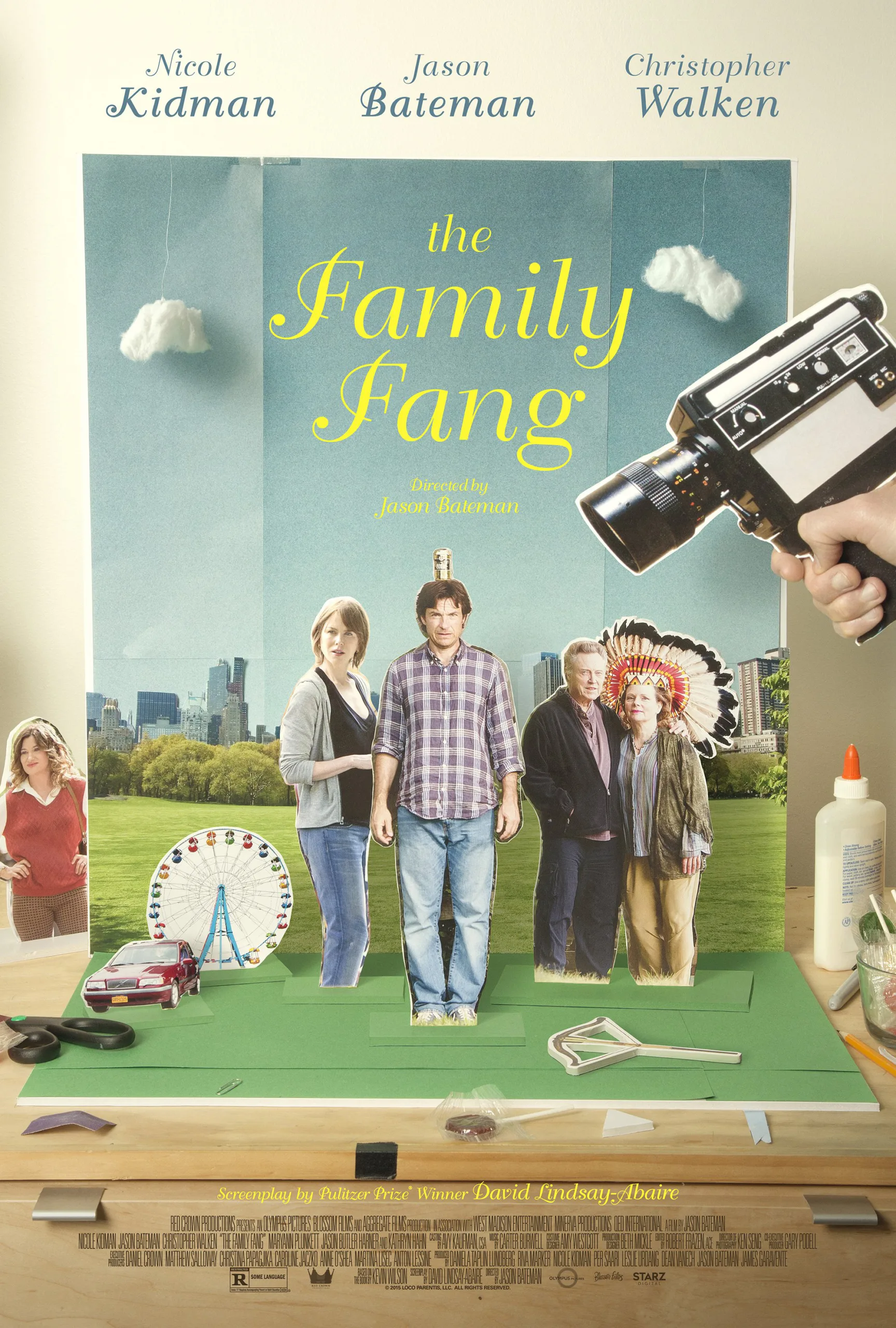

Directed by co-star Jason Bateman, from a script by David Lindsay-Abaire, based on a novel by Kevin Wilson, “The Family Fang” is largely noteworthy for the specific place it locates generational resentment. Bateman and Kidman play siblings, advanced adults no longer living up to their early promise. Once a Guy-In-Your-MFA tyro novelist, Bateman’s Baxter is now years past the deadline for his next book. Kidman’s Annie, an actress, has drunk her way out of a recurring role in a lucrative superhero franchise and is reduced to being wheedled into nude scenes by abusive directors of lame indies. Where is the locus of their dysfunction? Of course, in the larger family unit: their parents, Caleb and Camille, performance/conceptual artists of the ‘60s and ‘70s who forced their kids—whom Caleb initially referred to merely as “Child A” and “Child B”—to participate in stunt-like pieces. Many of which are recreated in further flashbacks.

There’s an interesting reactionary quality in the way the movie makes conceptual art its straw man, standing in for Irresponsible Parenting By The Counterculture. I don’t know if the Revenge Of Gen X And Or Y subtext was very strong in Wilson’s novel (I can hazard a guess though, that when he was writing it, he probably envisioned Wes Anderson as the Dream Director for the film adaptation), but here it flounders just like every other aspect of the movie, including the “what really happened” plot thread of Caleb and Camille’s disappearance shortly after they rudely reintroduce themselves into their children’s lives.

While the cast keeps its head down and reaches for genuine emotion, the movie eventually manages to sentimentalize even what it sees as its own tough-mindedness. The major exception, and the reason I’m rating this movie higher than I would otherwise, is Christopher Walken. His commitment to making Caleb as thoroughly unlikable as humanly possible yields a character who’s kind of terrifyingly off-putting even when his words and actions are ineffectual. A piece of acting alchemy of which only few are capable. I can’t imagine how powerful it might have been in a better movie.