Michael Winterbottom is a gifted filmmaker and storyteller, but watching him try to be a rhetorician can be painful. His best works of humanist agitprop are “In This World” and “Road to Guantanamo,” gripping dramas that humanize political problems, respectively the immigration crisis and torture, by showing the world through the eyes of disenfranchised people. In these films, Winterbottom’s politics are felt rather than argued.

Unfortunately, “The Emperor’s New Clothes,” Winterbottom’s new documentary about comedian-turned-populist-political-commentator Russell Brand‘s revolutionary shenanigans, is more like “The Shock Doctrine,” Winterbottom’s adaptation of Naomi Klein’s tract on disaster economics. Both of Winterbottom’s money-minded documentaries are essentially film-length arguments that also happen to appeal to our emotions. Worse still: because “The Emperor’s New Clothes” is often beholden to the whims of Brand (star of “Get Him to the Greek,” and that tedious “Arthur” remake nobody saw), it too often feels like “Button-Pushing Encounters with Russell Brand.”

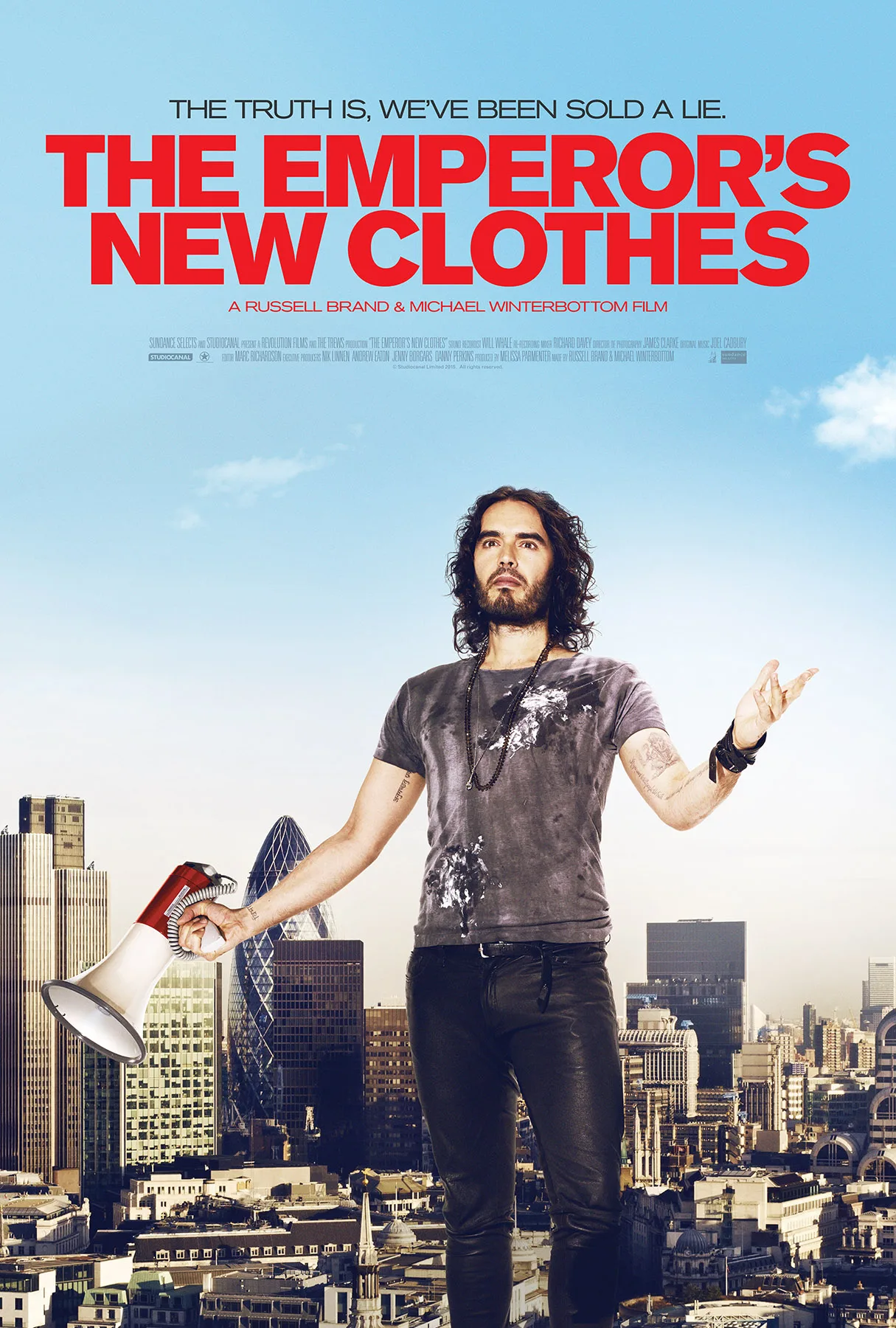

I didn’t know much about Brand’s political humor before seeing “The Emperor’s New Clothes” beyond watching bits of his YouTube videos wherein he holds court like a hipster Socrates. But the image that Brand presents of himself in “The Emperor’s New Clothes” is split between two modes: a counter-cultural man of the people who ribs the working class and presses the flesh, and a coy agitator who insists that the world’s bankers be jailed for their crimes against the underclass.

I am not a billionaire. I am one of the oppressed little choir members that Brand is preaching to. I should be the audience for this film. But I did not buy Brand’s two-pronged argument, because I did not find his whimsical argumentation to be intuitively ingenious. The comedian Eddie Izzard can pull off an improvised routine by sheer force of conviction, but Brand comes off as a performance artist, kissing babies in one scene and coming on like Robespierre in the next. You probably have to be an initiated member of Brand’s cult to be on the same page as him.

Through breathless monologues, he rails against the bankers who have yet to pay for institutionalized crimes like tax evasion and insider trading. Financial inequality is Brand’s biggest beef, so he tosses off statistics and quotations in the vain hopes that his scruffy, Jesus-as-a-toned-squeegee-man charms will make you want to listen to him long enough to hear him. Brand gets on his soapbox and talks right at Winterbottom’s passive camera, he talks about radical Chicago School economist Milton Friedman’s impact on Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan’s free-market economics policies. He quotes Joseph Campbell and talks about the persecution of London rioters in 2011. He breaks down how various banks’ CEOs have squirreled away billions in bonuses in off-shore trusts. This is Brand’s Sermon on the Mount. Watch, listen, zone out for a moment or two when it gets boring and then … wait, what was he saying?

Then Brand stops speechifying, and turns “The Emperor’s New Clothes” into his own trickle-down version of Michael Moore’s “Roger and Me.” He’s a lot more convincing when he’s acting like a rabble-rousing intellectual than when he’s talking to people who make a lot less money than he does. Brand camps out at various banks’ lobbies, teasing security guards about what he’s going to say to their presidents about tax evasion and the minimum wage when he eventually meets with them. These scenes stink, because they divide the working class into two sub-classes: plebes that either lick or bite the hands that feed them. Hand-lickers get short-changed because, while they are just doing their jobs, they’re also protecting bad people. Apparently this makes them fair game for Brand’s style of cheerful bullying.

The filmmaking keeps trying to convince us that Brand is not a real jerk but a comedian. Look at him use a pack of adorable, all-white children, armed with prop gold bars and a grade-school education to illustrate his point about the massive gap between the 1% and the 99%. Don’t look at his rock-star leather pants; look at his scrappy wool beanie: is this not a man of the people? The scenes of Brand talking to people on the street are the film’s worst. He looks like a tourist on holiday, sharing vacation photos with us. Here he is wending his way through the throngs of people at the Occupy movement rallies. And here he is talking to some women—real, working-class women—and embracing their fawning daughter while saucily talking about how poor people were unlucky enough to be born from the wrong vagina. And look, here’s Russell talking to a woman with cerebral palsy who has struggled for years to get off welfare.

This last scene is appalling for its hand-wringing pseudo-sincerity. It’s the moment where I stopped rolling my eyes at the film and became genuinely upset with Brand, the self-loving star, and Winterbottom, his enabler. Brand does not look earnestly engaged with his handicapped subject when he listens to her. Instead, he appears camera-ready: he knows he’s being watched, so he plays the role of the sensitive listener.

When talking to the women of his hometown of Grays, he puts on a big show of concern. This scene takes place long after Brand has shown us, the privileged viewer, an infographic breakdown of how outsourcing screws over the people of Grays. So when Brand asks the women of Grays if life has “gotten better or worse” and they say “better,” you know he’s only asking for appearance’s sake. He, and we, already know the answer.