In theory, a person like myself ought to be all about “The Duke of Burgundy,” the odd new film directed by Peter Strickland. Now that’s not to say that the theory would be my own, but let’s just say I’d have to concur with it. “Burgundy,” which is British director Strickland’s third feature-length film, is, like Strickland’s prior, “Berberian Sound Studio,” a bit of a journey into the past, and a very particular past. Where “Berberian” situated itself in the world of 1970s Italian horror filmmaking, the better to pay effective homage to it while also crafting an evocative psychological thriller, “Burgundy” harks back to the heyday, such as it was, of cheap European sexploitation cinema. Cinema that tarted itself up with fake-erudite allusions to Sade and/or Sacher-Masoch, cinema that offered cheap thrills on cheaper film stock but often flirted—or in some case consummated an actual relationship—with the genuinely surreal and/or sadistic.

So, the reason that I’d be likely to be all about “Duke” is because I’m a known admirer of a lot of such work—the films of disreputable-to-the-respectable-cinephile directors such as Jess Franco, Jean Rollin, all those guys. I’ve been examining their stuff since back when the only way you could get it in the U.S. was on dubious VHS transfers from merchants with names like “Video Search Of Miami” and so on. I’ve been a subscriber to “Video Watchdog” since it launched. I introduced “Psychotronic Encyclopedia of Film” author Michael Weldon to current “New York” film critic David Edelstein something like thirty years ago. And so on.

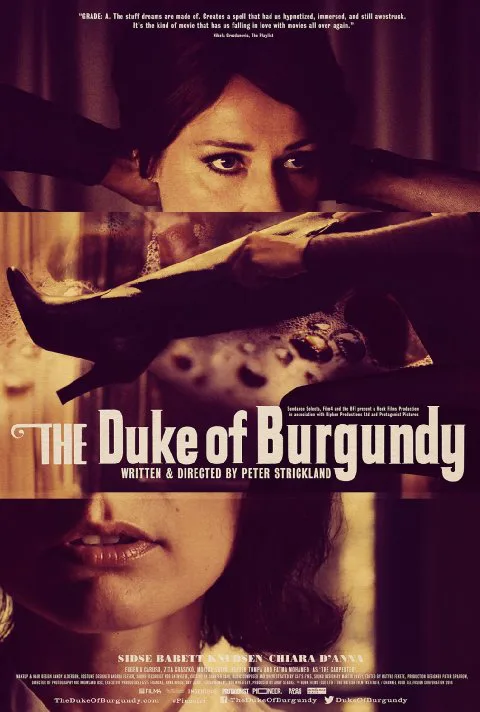

Strickland’s film is a daring, atmosphere-soaked piece of kink hypnotherapy that pays explicit homage to the films of Franco, down to the casting of former Franco regular, formidable femme Monica Swinn, in a sinister role. It’s not a horror film per se, and is in fact a little comedic in its overt content. The two main characters, Cynthia (Sidse Babbett Knudsen, looking rather more severe here than she did in “Mifune,” the 1999 Dogme film for which she’s best known in the States) and the younger Evelyn (Chiara D’Anna), who’s perhaps her protégé, are both engaged in heavy entomological studies and are also lovers. In their capacity in the latter department, they are seriously role-playing lovers, with Evelyn in the sub role and Cynthia doing the domming. There’s all manner of restraint, strictness, and general severity in their scenarios, but it becomes pretty clear right off the bat that their roles as lovers are not analogous to their roles in the relationship outside the role playing. That is, Evelyn has very specific demands as to how she needs to be dominated, while Cynthia is insecure and in need of direction and always scared she’ll botch things…and you also get a sense that deep down inside, she’d be much happier with just a regular lesbian relationship.

This is where the comedic aspect of the whole thing comes in. For a lot of us who have little or no experience with the rituals or sadomasochism or any of that other kind of stuff, one question that occurs is how do people who ARE into that sort of thing manage to keep a straight face while saying “Yes, Mistress,” or whatever. The problem for Evelyn and Cynthia isn’t so much the straight face but the level of commitment, and it cuts both ways. One of Evelyn’s favored scenarios entails her being bound and spending the night in a sealed chest. Invariably when the lovers try this out, it isn’t long before Evelyn starts peeping out the couple’s safe word, “Pinastri,” which, you know, in this case means “let me out!”

There’s something droll about all these doings, which alternate between bizarre scenes of insect knowledge delivered in a lecture hall and long-shot glimpses of a leering nosy neighbor (Swinn) in the adjoining yard to the couple’s ornate residence. And that’s pretty much the whole of the movie: there is very little of what you’d call a plot, which is also true of the movies “Burgundy” pays homage to; they often took an elliptical approach to story either by perverse design or micro-budget-triggered sloth or some combo thereof. Here it’s all very deliberate, and in keeping with the movie’s lush aural and visual surfaces; while soft focus and zooms are in no short supply here, the execution is a lot creamier, and more polished, than what the impoverished auteurs of the old days could muster.

Why am I not crazier about the film? It certainly is, at least, a mildly seductive exercise in sound and vision; but while the visuals are always arresting, they are rarely entirely compelling. As much admiration as I had for Strickland’s vision (ably captured by cinematographer Nicholas D. Knowland), there was also something about it that struck me as rather fussy. In the Franco (and Rollin) films that Strickland so clearly admires, there were multiple elements of anarchy and/or amateurism that could even accidentally propel the movie into a realm of seemingly genuine danger. This filmmaker has things very well under control (to the extent that he’s able to stage and shoot more than one ostensibly explicit love scene without revealing any nudity, which I know sounds like I’m complaining, but honestly, that’s not it) and as such the feel of pastiche is kind of inescapable. The thing is, if you recognize the names of the filmmakers I’ve alluded to in this review, you identified yourself as its core demo before you go to the end of the first paragraph. You will see the movie whether I give it a thumbs-up or not! As for everybody else? What can I say? Proceed with care. If you’re in the mood for something different…something possibly completely different…this will fill the bill.