The French believe that most of the characters in American movies, no matter what their age, act like teenagers. I believe that the teenagers in most French movies seem old, wise and sad. There is a lesson here, perhaps that most American movies are about plots and most French movies are about people.

“The Dreamlife of Angels” serves as an example. It is about two 20-year-olds who are already marked by the hard edges of life. They meet, they become friends, and then they find themselves pulled apart by sexuality, which one of them sees as a way to escape a lifetime of hourly wages. This is a movie about a world where young people have to work for a living. Most 20-year-old Americans in the movies receive invisible monthly support payments from God.

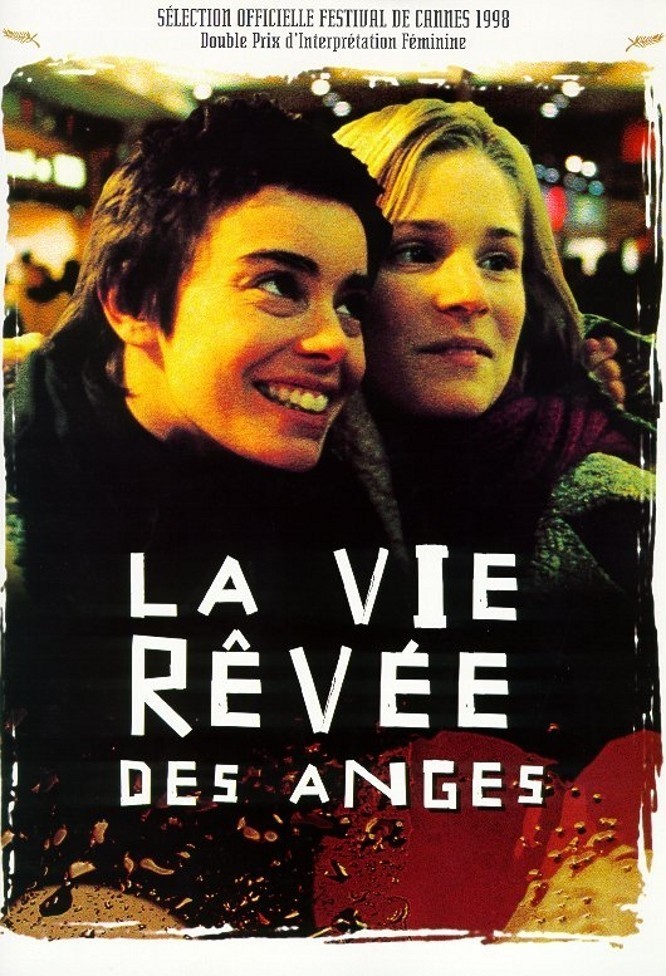

We meet Isa (Elodie Bouchez), a tough little nut with a scar over one eye and a gift of gab. She’s a backpacker who cuts photos out of magazines, pastes them to cardboard squares and peddles them in bars as “tourist views.” She doesn’t really expect to support herself that way, but it’s a device to strike up conversations, and sure enough, she meets a guy who offers her a job–working as a seamstress in a sweatshop.

At work, she meets Marie (Natacha Regnier). The two become friends, and Isa moves in with Marie. They hang out in malls and on the streets, smoking, kidding, playing at picking up guys. They aren’t hookers; that would take a degree of calculation that they lack–and, besides, they still dream of true romance. Isa tells Marie about one guy she met when she was part of a remodeling crew working on his house. They slept together, but when the job was over, she left, and he let her leave. She wonders if maybe she missed a good chance. Unlikely, Marie advises. Marie steals a jacket and is seen by Chris (Gregoire Colin). He owns a club, and asks them to drop in one night. They already know the bouncers, and Marie has slept with one of them. Soon it comes down to this: Chris has money, Marie has none, and although her friendship with Isa is the most important relationship in her life, she is willing to abandon it in order to share Chris’ bed and wealth. Isa, who in the beginning looked like a mental lightweight, has the wisdom and insight to see how this choice will eventually hurt Marie. But Marie will not listen.

The movie understands what few American movies admit: Not everyone can afford the luxury of following their hearts. Marie has already lost the idealism that would let her choose the bouncer (whom she likes) rather than the owner (whom she likes, too, but not for the same reasons). The story is played out against the backdrop of Lille, not the first French city you think of when you think of romance. In this movie it is a city of gray streets and tired people, and there is some kind of symbolism in the fact that Marie is house-sitting her apartment for a girl in a coma.

The movie was directed and co-written by Erick Zonca, a 43-year-old Parisian who lived in New York from the age of 20, worked at odd jobs for 10 years, then became the director of commercials. He returned to France to make his features; this is his third. He creates an easy familiarity with Isa and Marie. The story is about their conversation, their haphazard progress from day to day; it doesn’t have contrived plot points. I can’t easily imagine Isa and Marie in Los Angeles, nor can I imagine an American indie director making this film, which contains no guy-talk in diners, no topless clubs, no drug dealers in bathrobes, no cigars. This year’s Critics Week at Cannes has just announced that it was unable to find a single American film it admired enough to program. “The Dreamlife of Angels” shared the best actress award between Bouchez and Regnier last year in the Cannes main competition. There you have it.