Anyone who has ever been through the medical system – even with the very best of treatment – will identify with this film. “The Doctor” tells the story of an aloof, self-centered heart surgeon who treats his patients like names on a list. Then he gets sick himself, and doesn’t like it one bit when he’s treated like a mere patient.

“It may interest you to know that I happen to be a resident surgeon on the staff of this hospital!” he barks at a nurse who wants him to fill out some forms just like the ones he has already filled out. He still has to fill out the forms.

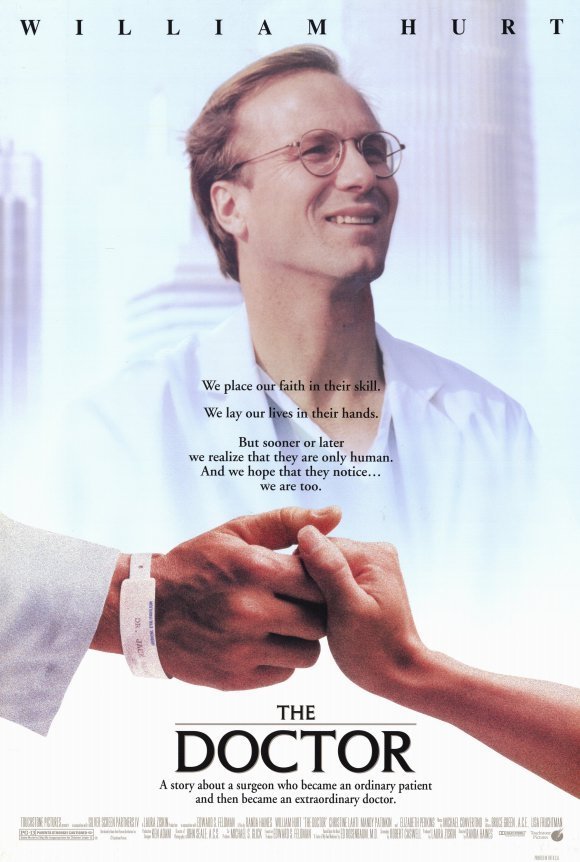

The role is played in a detailed, observant way by William Hurt, who is able to make this egocentric surgeon into a convincing human being. In the wrong hands, this material could have been simply a cautionary tale, but Hurt and his director, Randa Haines, who also collaborated on “Children of a Lesser God,” make it into the story of a specific, flawed, fascinating human being.

As the movie opens, Hurt plays rock ‘n’ roll into his operating theater while literally holding the hearts of his patients in his hands. He leads a comfortable life in Marin County, Calif., with his wife (Christine Lahti) and two sons, but is not very close to his family. (In one revealing scene, he’s standing in the living room when a son races in. “Say hello to your father,” Lahti says, and the kid automatically picks up the phone.) In his lectures to the interns at the hospital, Hurt warns that personal feelings have nothing to do with the science of medicine. Then he discovers otherwise.

His problem starts as a small, nagging cough. He ignores it until one day he coughs up blood. He goes to an eye, ear, nose and throat expert (played with cold precision by Wendy Crewson), and discovers that there is a tumor in his throat. It is malignant. He needs radiation therapy. If it doesn’t work, he may need surgery. In that case, it’s impossible to predict how his vocal cords will respond. He could lose the power of speech.

This is devastating news, which he receives with disbelief. How could a master of medicine like himself become its victim? As his treatment progresses, he doesn’t like how his own hospital treats him, as he wastes time in waiting rooms, tangles with the bureaucracy and is repelled by Crewson’s frigid bedside manner. For the first time, he grows close to a patient, June (Elizabeth Perkins), who has a brain tumor. They meet daily while they’re having their treatments.

The broad outlines of the story progress more or less as expected. Threatened with his own mortality, he turns to June not for romantic reasons but as a fellow traveler in the same path. Their scenes together are handled with quiet tact and gentleness. Although his wife desperately tries to break through to him, she can’t reach him (“I’ve spent so much time pushing her away, I don’t know how to let her get close,” he confesses). He continues to work at his own practice and finds that for the first time he actually, personally, cares about his patients.

In structure, “The Doctor” is similar to the current “Regarding Henry.” Both movies are about successful professional men who are monsters until a devastating event forces them to reshape their personalities. The difference is that Hurt, Haines and writer Robert Caswell are able to find the details, the intonations and shadings of voice and tone that make their doctor into a plausible, convincing person. In “Regarding Henry,” I could always hear the hum of the plot mechanism, right offstage.

I imagine audiences will relate strongly to “The Doctor,” because most people have had experiences similar to those in the movie. I personally have been blessed with what I consider particularly expert and caring medical attention, and I have no complaints. But I have a memory.

A few years ago I was struck low by food poisoning and checked into the hospital as sick as a whipped dog. Wearing one of those hospital gowns designed to remove the last vestige of dignity from the patient, I was taken by wheelchair to get some tests and was parked by an elevator. I lacked even the strength to lift my head.

Sure enough, half the people who went by recognized me from TV. But they didn’t talk to me. They talked about me. “Look, there’s the guy on TV! Jeez, he looks terrible!” In “The Doctor,” there’s a scene where the Hurt character is being wheeled toward surgery, and some doctors hold a technical conversation practically across his cart. He lifts his head, contributes some expert advice, and then, when they look at him in surprise, says, “Yes! There’s a person here!” I felt like cheering.