Mike Nichols‘ “Regarding Henry” opens with a portrait of a Manhattan lawyer as a driven, ambitious man who lives in great wealth and little happiness. Then a catastrophe occurs. He steps out one night to buy some cigarettes, and is shot in a holdup. One of the bullets penetrates his brain, and for weeks he drifts in a coma, until finally he awakens and the long process of rehabilitation can begin.

The movie is essentially about how Henry becomes more lovable and human as a result of his injury – how his soul is healed and his family saved by the experience. The shock of the bullet to his brain is diminished for the audience because all of the advertising for this movie, including the trailers and the TV commercials, spoil the surprise. But the movie isn’t really about the gunshot wound, anyway.

It’s about how a man becomes a child, and the change is for the better.

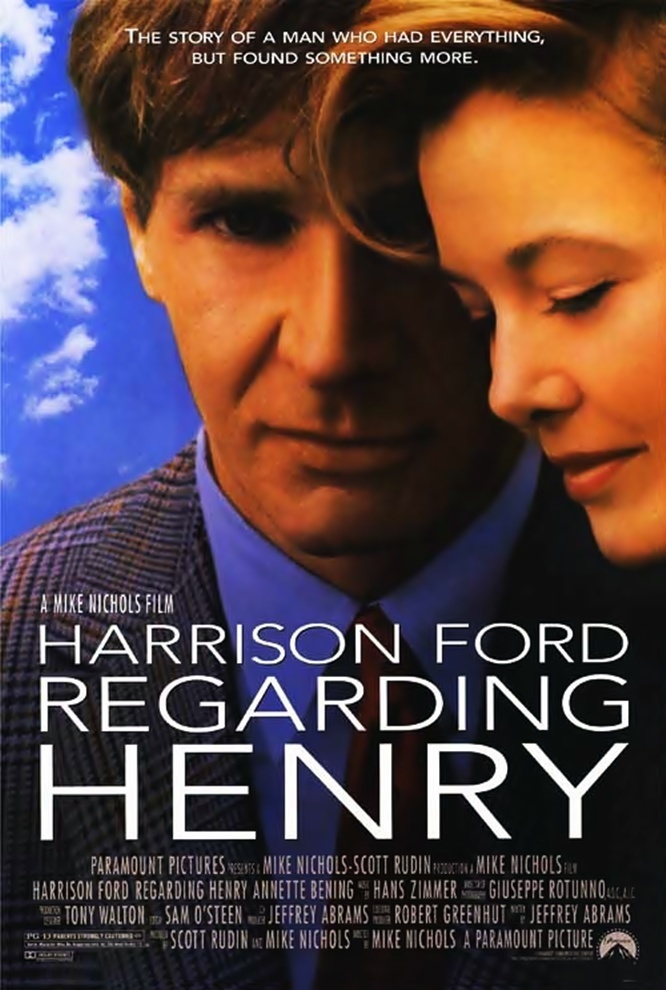

The original Henry is played by Harrison Ford as a taciturn taskmaster who treats his young daughter as if she were a balky client and his wife (Annette Bening) as a partner with whom he is friendly but not intimate. After the grievous wound to his brain, Henry recovers into an altogether more pleasant person. He can remember almost nothing of his previous life, to be sure, and has to take it on trust that he has this wife and daughter. But with the directness of a child he values honesty and loyalty, two qualities the old Henry was not familiar with.

There is possibly a good movie to be found somewhere within this story, but Mike Nichols has not found it in “Regarding Henry.” This is a film of obvious and shallow contrivance, which aims without apology for easy emotional payoffs, and tries to manipulate the audience with plot twists that belong in a sitcom.

Genuine issues – such as the family’s economic insecurity and the wife’s reaction to the end of her days in a gilded cage – are glossed over. But there is time for a soap opera subplot about office affairs, and lots of time for Henry to confront the dishonesty in his old law firm.

For much of the film, Henry is an attractive, likeable, simple-minded and childlike character. But exactly how simple-minded? The movie seems to treat his mental acuity as a matter of convenience; he is childlike enough to say embarrassing things in public, but clever enough to know what’s really going on, and to outsmart his old law colleagues. A pattern emerges: We begin to notice, after awhile, that in any given scene Henry will possess the necessary mental development to deliver the punch line. He isn’t a character, he’s an act.

The wife and daughter are his props. Parts of Bening’s character seem to have been lopped away in the editing, so that she asks questions that are never answered. Try to follow, if you can, her thoughts about her family’s financial situation, as Henry eventually loses his income and the family moves to a smaller (but by no means shabby) home. There are all sorts of little scenes scattered through the movie that seem intended to make the financial situation into an important subplot, but there’s never a payoff. It’s dropped.

Ask yourself, too, exactly what goes on in the physical life between husband and wife, and you’ll find another thread that’s hard to untangle. A little easy romance glosses over what should have been scenes of awkward rediscovery. Bening and Ford work hard during their more intimate scenes together, but they haven’t been given the dialogue of truth and tentative exploration that they need to work with.

The screenplay by Jeffrey Abrams, in fact, constantly goes for the laugh over the possible reality. It has an annoying trick of teaching Henry a new word and then having him proudly trot it out to wrap up a complicated scene. The way the movie makes a connection between Ritz Crackers and the Ritz-Carlton hotel is especially annoying, combining cheap sentiment with a cheap laugh – and cheap product placement.

I was not very moved, either, by the process of Henry’s physical and mental rehabilitation, during which a physical therapist (Bill Nunn) uses Pavlovian techniques to restore Henry’s powers of speech. (He can’t say anything? Put a lot of Tabasco on his eggs – that’ll get him to talk!) Compared to the real-life experiences of gunshot victims like James Brady, Henry’s experiences belong in a sitcom. All of the stages of his recovery correspond neatly to the requirements of the plot.

The ending of the film shows Nichols reaching back to the barn-burning formula that paid off for him in “The Graduate,” where Benjamin disrupted the wedding ceremony with his cry of anguished hope and love. Again this time, the ritual of a staid public ritual is rudely interrupted by the arrival of a seeker after truth. But it’s so neat, so formula, so contrived, I was thinking about “The Graduate” instead of about characters I had spent two hours with. So, I suspect, was Nichols.