For his debut feature film, writer/director David Freyne has come up with the best kind of premise, the sort of thing that’s so irresistible in its simplicity that people who didn’t think of it get annoyed that they didn’t think of it. (That’s the thing about such irresistibly simple ideas—they’re actually not easy to come up with.) While scads of prior horror movies have merely inundated viewers with horrific stories about our friends and loved ones turning into flesh-eating undead monsters, “The Cured” imagines a world in which the thing that created such horrors is indeed a virus, and one for which a cure has been found. The world is ours, and the country is Ireland.

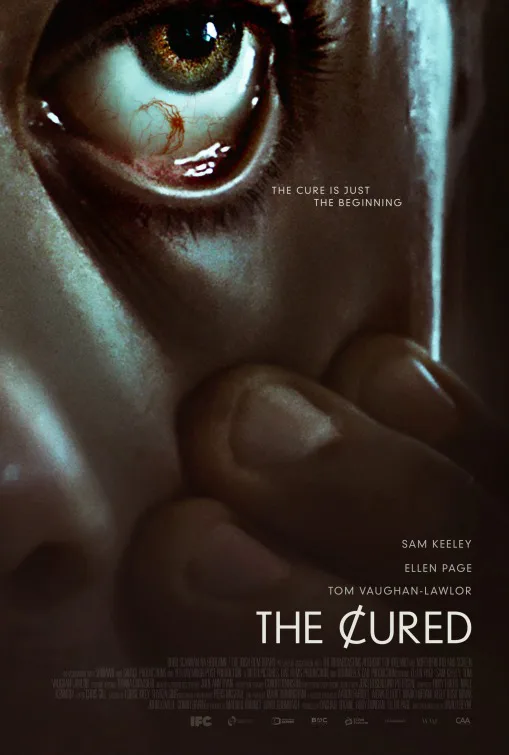

The movie begins with a bloody sneaker, and a young man breathing heavily, ever more heavily, as a bloodthirsty expression takes hold of his face. This is Senan, played terrifically by Sam Keeley. The quick visions of his former self come to him in flashbacks and nightmares. Now, after an injection and hospital stay, he’s normal again. There’s a circle of blood in the lower white of his eye that’s a mark of his former state. He and other cured are released into the general populace under the supervision of a none-too-pleased military man. Protestors distrust them. The cured, at least the most conscientious of them, don’t trust themselves. Because they can remember what they did. And what Senan did what especially terrible.

Still, Senan has a home: that of his sister-in-law Abbie (Ellen Page), an American journalist and the widow of Senan’s brother. Abbie and her little boy welcome Senan, but most of the cured are not so fortunate. There’s Conor, for instance, who seems frail and gentle upon release; he has a bond with Senan that articulates itself in great physical closeness. Conor was once a prominent lawyer, now he’s something like a sanitation worker, rejected by family. As Conor tries to draw Senan into an insurrectionist group, and also ingratiate himself into Abbie’s life, he becomes more and more forceful. The performance here by Tom Vaughan-Lawlor is particularly vivid.

Meanwhile, in a medical facility cum prison, a group of what are called “the resistant,” virus victims for whom the cure doesn’t take, are about to be wiped out by the government. The developer of the cure races against time to synthesize a new version of the medicine, in part to save her own lover from death. Senan is enlisted as a medical assistant there. He’s useful because the currently infected never attack one of their own, and they still recognize the cured as that. This glitch leads to all sorts of interesting plot complications and loopholes. Freyne’s scheme also makes potent use of ideas developed in George A. Romero’s “Dead” series, particularly those about undead intelligence evolution put forward in “Day of the Dead.”

The result is a very creepy, suspenseful story that’s also a better-than-average character study. And as you may have inferred upon my saying the film was set in Ireland, the premise has a great deal of potential for allegory and metaphor. Freyne’s hand here is assured; his world-creation (the cities are postered with PDAs about handling the crisis of what’s called “The Maze Virus”) doesn’t lay things on too thick, but the points concerning trust, distrust and the weight of history and personal conscience are all hit with a satisfying directness. Eventually, the tension between the characters and their individual situations has to break, and this is the point at which the movie becomes its most conventional, with riots and chases and near-misses in the bit-by-one-of-the-infected department. For its familiarity, it’s still engaging, and the final shots have a nice sting in the tail. Freyne is a filmmaker to watch, to be sure, and “The Cured” is going to be a genre film to beat in 2018.