“The Count of Monte Cristo” is a movie that incorporates piracy, Napoleon in exile, betrayal, solitary confinement, secret messages, escape tunnels, swashbuckling, comic relief, a treasure map, Parisian high society and sweet revenge, and brings it in at under two hours, with performances by good actors who are clearly having fun. This is the kind of adventure picture the studios churned out in the Golden Age–so traditional it almost feels new.

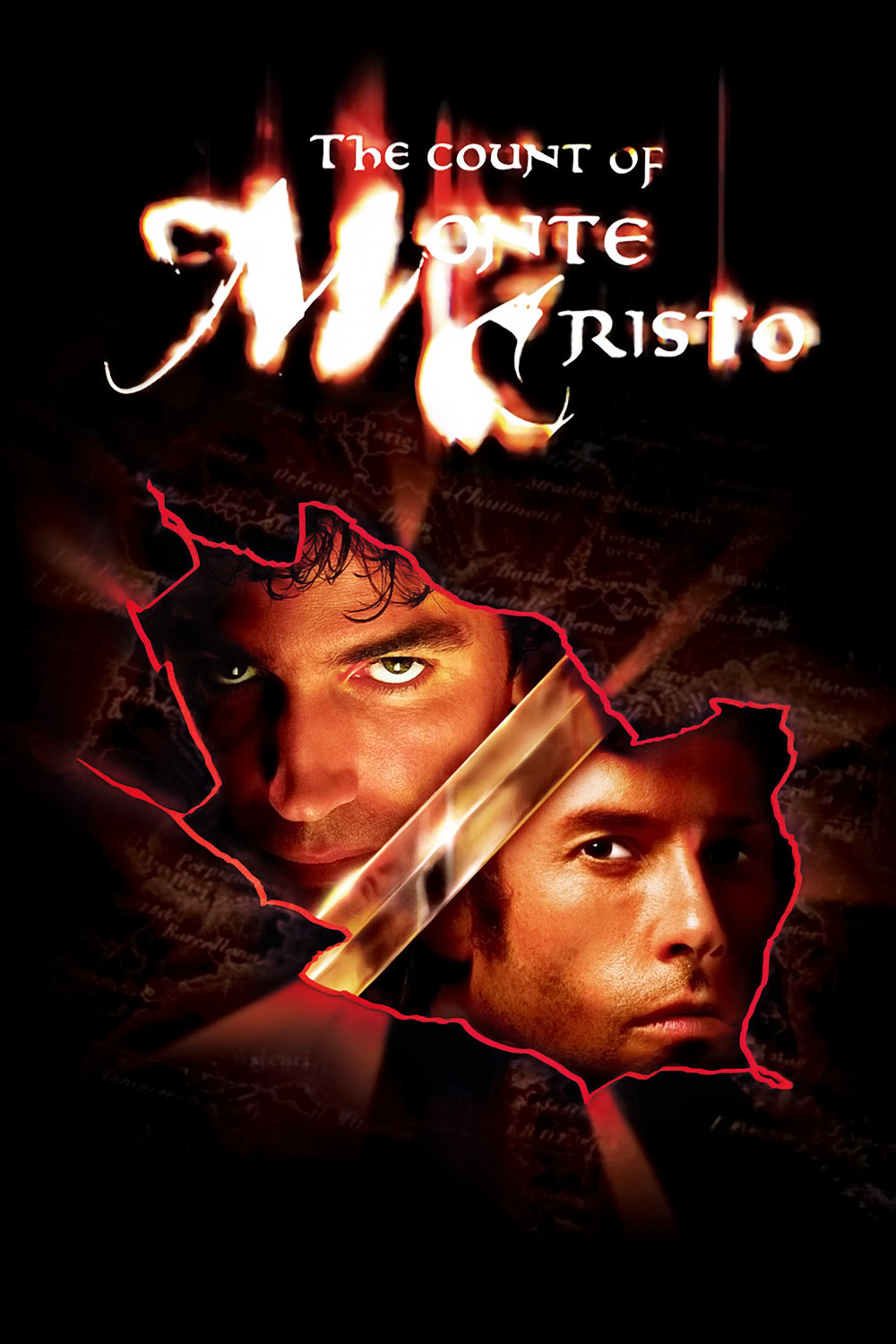

Jim Caviezel stars, as Edmund Dantes, a low-born adventurer betrayed by his friend Fernand Mondego (Guy Pearce). Condemned to solitary confinement on the remote prison island of Chateau d’If, he spends years slowly growing mad and growing his hair, until one day a remarkable thing happens. A stone in his cell floor moves and lifts, and Faria (Richard Harris) appears. Faria has even more hair than Dantes, but is much more cheerful because he has kept up his hope over the years by digging an escape tunnel. Alas, by digging in the wrong direction, he came up in Dantes’ cell instead of outside the walls, but c’est la vie.

“There are 5,119 stones in my walls,” Dantes tells Faria. “I have counted them.” Faria can think of better ways to pass the time. Enlisting Dantes in a renewed tunneling effort, he also tutors him in the physical and mental arts; he’s the Mr. Miyagi of swashbuckling. Together, the men study the philosophies of Adam Smith and Machiavelli, and the old man tutors the younger one in what looks uncannily like martial arts, including the ability to move with blinding speed.

This middle section of the movie lasts long enough to suggest it may also provide the end, but no: The third act takes place back in society, after Faria supplies Dantes with a treasure map, and the resulting treasure finances his masquerade as the fictitious Count of Monte Cristo.

Rich, enigmatic, mysterious, he fascinates the aristocracy and throws lavish parties, all as a snare for Mondego, while renewing his love for the beautiful Mercedes (Dagmara Dominczyk).

The story of course is based on the novel by Alexandre Dumas, unread by me, although I was a close student of the Classics Illustrated version. Director Kevin Reynolds redeems himself after “Waterworld” by moving the action along at a crisp pace; we can imagine Errol Flynn in this material, although Caviezel and Pearce bring more conviction to it, and Luis Guzman is droll as the count’s loyal sidekick, doing what sounds vaguely like 18th century standup (“I swear on my dead relatives–and even the ones that are not feeling so good”).

The various cliffs, fortresses, prisons, treasure isles and chateaus all look suitably atmospheric, the fight scenes are well choreographed, and the moment of Mondego’s comeuppance is nicely milked for every ounce of sweet revenge. This is the kind of movie that used to be right at home at the Saturday matinee, and it still is.

Footnote (read no further if you plan to see the movie) : There is one logistical detail that mystifies me. After Faria is killed in a cave-in, Dantes arranges for his dead body to be found, then substitutes himself for the corpse, is carried out of the prison and finds his freedom. All very well. But why, given the realities involved and the need to make haste, does Dantes go to the trouble of moving Faria’s corpse to Dantes’ own cell–thus supplying a premature warning of the switch, and betraying the fact of the tunnel’s existence? If he is recaptured, that tunnel might come in handy.