In the town of Kingdom Come, winter is more of a punishment than a season. High in a pass of the Sierra Nevada mountains, its buildings of raw lumber stand like scars on the snow. The promise of gold has drawn men here, but in the winter there is little to do but wait, drink and visit the brothel. The town is owned and run by Mr. Dillon, a trim Scotsman in his 40s who is judge, jury and (if necessary) executioner.

I dwell on the town because the physical setting of Michael Winterbottom’s “The Claim” is central to its effect. Summer is a season for work, but winter is a time for memory and regret. Mr. Dillon (Peter Mullan) did something years ago that was wrong in a way a man cannot forgive himself for. He lives in an ornate Victorian house, submits to the caresses of his mistress, settles the affairs of his subjects and is haunted by his memories.

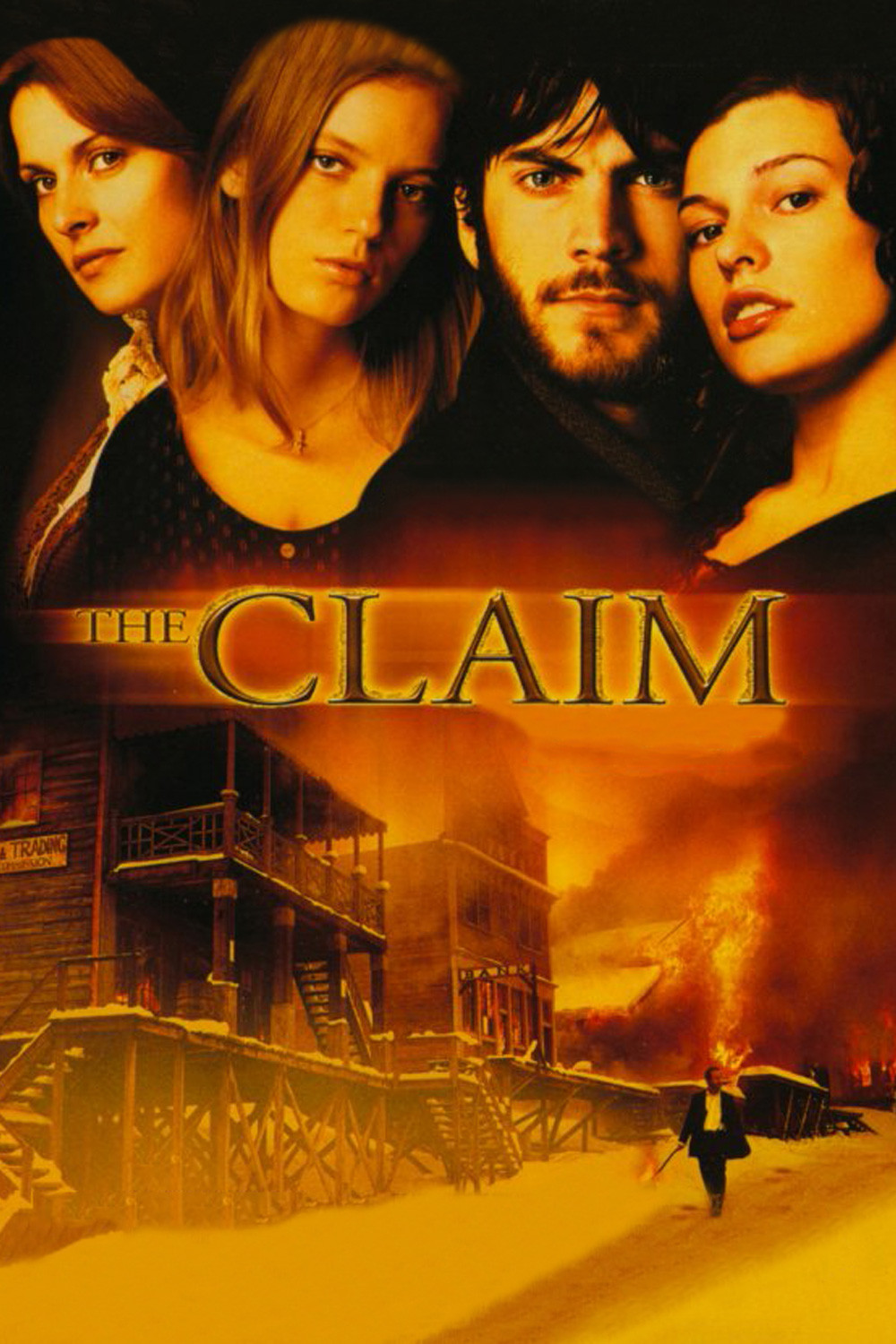

Two women arrive in Kingdom Come. One is a fading beauty named Elena (Nastassja Kinski), dying of tuberculosis. The other is her daughter, about 20, named Hope (Sarah Polley). They have not journeyed to Kingdom Come to forgive Mr. Dillon his trespasses. It becomes clear who they are, but the movie is not about that secret. It is about what happened 20 years ago, and what, as a result, will happen now.

To the town that winter also comes Donald Dalglish (Wes Bentley), a surveyor for the railroad. Where the tracks run, wealth follows. What they bypass will die. Dalglish is young, ambitious and good at business. He attracts the attention of Lucia (Milla Jovovich), who is not only Mr. Dillon’s comfort but also the owner of the brothel. She kisses him boldly on the lips in full view of a saloon-full of witnesses, sending a message to Mr. Dillon: If he doesn’t want keep her, others will. Dalglish is not indifferent, but he is more intrigued by the strange young blond woman Hope, who stands out in this grimness like the first bud of spring.

The past comes crashing down around them all–and then the future arrives, to finish them off. Mr. Dillon’s fate, which he fashions for himself, is all the more complex because he has done great evil but is in some ways a good man. Nor is Dalglish morally uncomplicated. In the hard world they inhabit, no one can afford to act only on a theoretical basis.

“The Claim” is parsimonious with its plot, which is revealed on a need-to-know basis. At first, we’re not even sure who is who; dialogue is half-heard, references are unclear, the townspeople know things we discover only gradually. The method is like Robert Altman’s in “McCabe and Mrs. Miller,” and Antonia Bird’s in the underrated 1999 Western “Ravenous” (a movie that takes place in about the same place and time as this one). Like strangers in town, we put the pieces together for ourselves.

The movie is so rooted in the mountains of the American West that it’s a little startling to learn “The Claim” is based on Thomas Hardy’s 1886 British novel The Mayor of Casterbridge . Winterbottom filmed “Jude,” a version of Hardy’s Jude the Obscure, in 1996. By transmuting Hardy into a Western here, he has not made a commercial decision (Westerns are not as successful these days as British period pictures), but an artistic one, perhaps involving his vision of Kingdom Come, a town that is like a stage waiting for this play.

Winterbottom is a director of great gifts and glooms. His “Butterfly Kiss” (also 1996) starred Amanda Plummer in a great performance as a kind of homeless flagellant saint. Here he tells the story of another kind of self-punishing character, and Peter Mullan’s performance is private and painful, as a man whose first mistake is to give away all he has, and whose second mistake is to try to redeem himself by giving it all away again. Mullan (“My Name Is Joe“) is like a harder, leaner, younger (but not young) Paul Newman, coiled up inside, handsome but not depending on it, willing to go to any lengths to do what he must. Intriguing, how he makes a villain sympathetic, in a movie where the relatively blameless Dalglish seems corrupt.

A movie like this rides on its cinematography, and Alwin H. Kuchler evokes the cold darkness so convincingly that Kingdom Come seems built on an abyss. Like the town of Presbyterian Church in “McCabe and Mrs. Miller,” it is a folly built by greed where common sense would have steered clear. There are two great visual scenes, the arrival of the railroad and the moving of a house, one exercising public will, the other private will. The ending is uncannily like that of “McCabe and Mrs. Miller,” although for an entirely different reason.

Winterbottom is a director comfortable with ambiguity. In movies such as “Wonderland” (1999), “Welcome to Sarajevo” (1997) and others, he’s reluctant to corner his characters into heroism or villainy. In the original Hardy novel, the Dillon character, named Henchard, is a drunk who pays so well for his sins that he seems more like Job than a sinner being punished. Dillon, who was also a drunk, tells the woman he has wronged, “I don’t drink anymore. I want you to know that.” For his time and place, he has grown into a hard but not bad man, and when he has a citizen horsewhipped, the man explains that the town would have lynched him–the whipping saved his life.

The strength of “The Claim” is that Dillon and Dalglish are on intersecting paths; Dillon is getting better, while Dalglish started out good and is headed down.