Brandon Teena was a “good kisser” and “knew how to treat a woman,” we are told, and even after Brandon’s secret was revealed–“he” was a biological female born Teena Brandon–there is a certain wistfulness in the memories of her girlfriends. None of the women who dated Brandon seem particularly angry about the deception, and after we’ve spent some time in the world where they all lived, we begin to understand why: Most of the biological men in “The Brandon Teena Story” are crippled by a vast, stultifying ignorance. No wonder a girl liked a date who sent her flowers and little love notes. Consider, for example, the sheriff in the rural area where Brandon Teena and two bystanders were shot dead. We hear his words on tape as he interviews Brandon, who was raped by those who would commit the murders a few days later. To hear the interrogation is to hear words shaped by prejudice, hatred, deep sexual incomprehension and ignorance. I cannot quote most of what the sheriff says–his words are too cruel and graphic–but consider that he is interviewing not a rapist but a victim, and you will get some notion of the atmosphere in some corners of the remote Nebraska district where the murders occurred.

The sheriff did not like it one bit that a woman was pretending to be a man. There is the hint that a woman who behaves like this deserves whatever she gets; that it is natural for a red-blooded man to resent any poaching on his phallic preserve. The tapes also preserve the voice of Brandon, who was 20 or 21 at the time, and sounds very young, insecure and confused. “I have a sexual identity crisis,” we hear at one point.

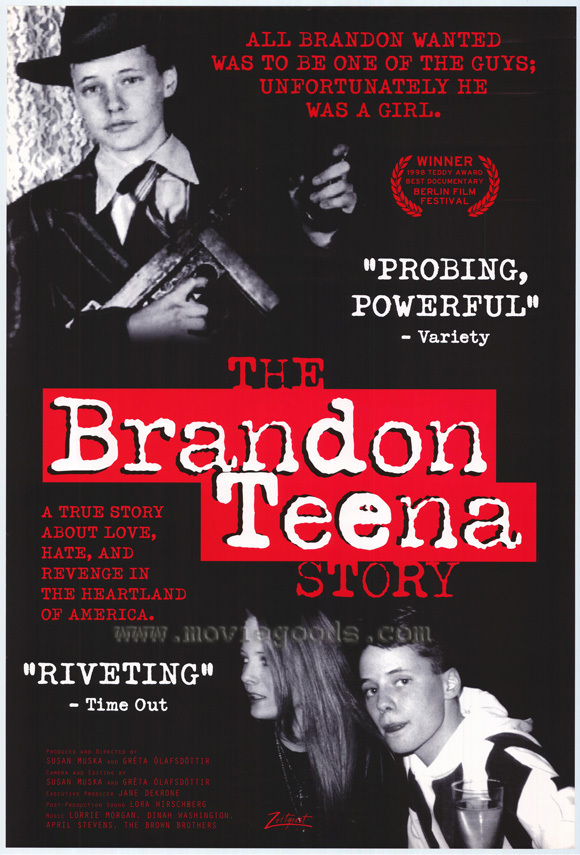

The documentary includes photos of Brandon, or Teena, at various ages, and although the clothing gradually becomes masculine and the haircut gets shorter, I must say that I never really felt I was looking at a man. Perhaps the deception would have worked only in a rural and small-town world far removed from the idea of gender transitions. The two men who were convicted of the murders were apparently deceived; they considered Brandon a friend, before growing suspicious and brutally stripping their victim of her clothes and, apparently, virginity.

But what about the women Brandon dated? Their testimony remains vague and affectionate. They were not lesbians (and neither was Brandon–who firmly adopted a male identity), but they were responsive to tenderness and caring and “good kissing.” One woman in the film dated one of the murderers as well as Brandon; given a choice between the narrow-minded dimness of the man and the imagination of someone prepared to cross gender lines, the more attractive choice was obviously Brandon.

The film itself is not slick and accomplished. It plays at times like home video footage, edited together on someone’s computer. There are awkward passages of inappropriate music, and repeated shots of the barren winter landscape. Oddly enough, this is an effective style for this material; it captures the banality of the world in which individuality is seen as a threat. The testimony in the film is often flat and colorless (the killers are maddeningly passive and detached). Even the hero, Brandon Teena, was only slowly coming to an understanding of identity and sexuality.

Watching the film, I realized something. It is fashionable to deride TV shows like “Jerry Springer” for their sensational guests (“My boyfriend is really a girl!”). But as I watched “The Brandon Teena Story,” I realized that Brandon lived in a world of extremely limited sexual information, among people who assumed that men are men and women are women, and any violation of that rule calls for the death penalty. To the degree that they have absorbed anything at all from church or society, it is that homosexuals are to be hated. If tabloid TV contains the message that everyone has to make his or her own accommodation with life, sex and self-image, then it’s performing a service. It helps people get used to the idea that some people are different. With a little luck, Jerry Springer might have saved Brandon Teena’s life.