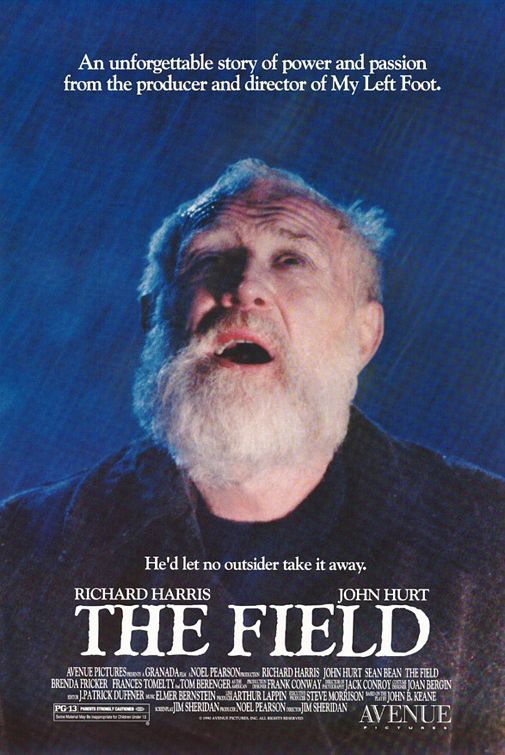

“The Field” is a grim allegory of hard life on the land – a symbolic play, transplanted uneasily to the greater realism of the film medium, where what we might accept on the stage now looks contrived and artificial. This was not a work that called out to be filmed. Once filmed, it calls out to be forgotten. But it will always have a footnote in cinematic history, because Richard Harris’ work has been nominated for an Academy Award in the best actor category.

Harris plays “Bull” McCabe, a weathered and bearded man of the soil, who has spent a lifetime tending a small field in his corner of Ireland. The time is the 1920s, but it could be the 1820s for all that life has changed in this soggy and overcast backwater, where the miserable McCabe and his retarded son, Tad, haul wicker baskets full of seaweed up the cruel cliffs and dump them on the field, as their fathers and the fathers of their fathers have done before them. Then a slick Irish-American (Tom Berenger) comes to town, smoking cigarettes and wearing a camel-hair overcoat, and he wants to buy the field, in order to strip-mine it, I think.

His arrival inevitably precipitates a crisis in the village, which can only be settled by rape, murder and a public auction, accompanied by no end of wise epigrams by the wizened local inhabitants, who have been waiting a generation for their chance to mutter profound sayings about the land and the people who live on’t. Harris growls and howls and looks like Lear as he wades about in the bitter sea and strides through the mud and peat, and there is no doubting this is a good performance, but in the service of a hopeless cause.

If I were watching this as a play, I might just be able to care about the field, if it were located far offstage. But the motion picture camera has an unforgiving way of photographing anything that is put before it, and so we can easily see that the McCabes, father and son and father’s father and all, have been wasting their efforts dragging that wet seaweed up the cliff to fertilize the field, because the village is surrounded by thousands of acres of prime pasturage. Tom Berenger is also on a fool’s errand. Why does he need to strip the field when if there is one thing the district has more of than fields, it is mineral rights, and if there is one thing it has no need of, it is gravel? No, this play is not about the field, it is about eternal questions. Questions about (1) a man’s right to the land, (2) whether the owner should sell out to the highest bidder and (3) whether the Irish in America have lost their respect for the land and its people, and forgotten the old ways. The answer to these questions, laid out here in dirge and lamentation, is that (1) if a man and his father and his father’s father spend their lifetime dragging seaweed up a cliff and dumping it on the land, they have, by God, a right to that land, (2) the owner should therefore sell it at a loss, or give it away, and (3) yes.