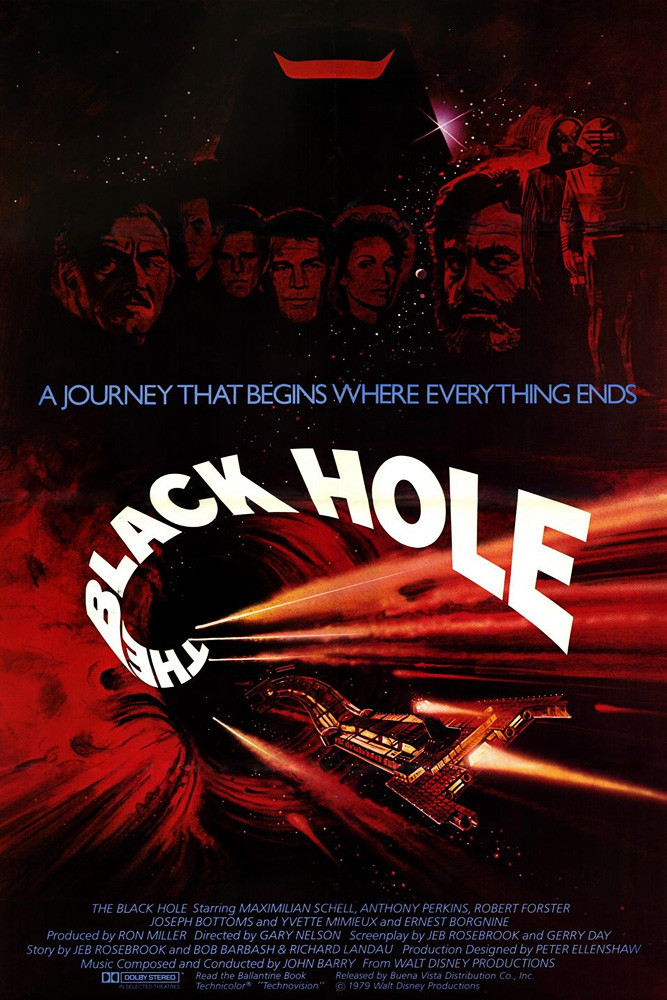

There’s something endearingly human about our ability to take the most astonishing ideas and treat them in trivial stories. Take, as today’s example, the idea of black holes in outer space and the story of Walt Disney’s “The Black Hole.”

The concept of black holes has trickled down by now from the ivory towers of Cambridge to the middle ground of Scientific American and finally to the funny pages: There may be special places in the universe where collapsing stars have set up gravity fields so dense that not even light can escape from them. So we have a “hole” in space which by definition we cannot see. Since light (which cannot help moving at the speed of light) cannot climb out of the hole. . . would an object falling into it be accelerated beyond the speed of light? And what would happen then?

The possibilities are mind-boggling. One of them, much favored by science-fiction writers, is that black holes are tunnels in space, and that if we fell into one we might emerge (a bit scorched, perhaps) from a “white hole” some. where else in the universe. Because black holes are “singularities” that do not correspond to models of the universe constructed by Einstein or anybody else, they’ve also inspired wonderfully apocalyptic notions. My favorite is that they’re intergalactic bathtub drains, and that we’ll all whirl down them some day and turn up in the sewer system of the universe next door.

That would be preferable to what happens in Disney’s “The Black Hole,” which takes us all the way to the rim of space only to bog us down in a talky melodrama whipped up out of mad scientists and haunted houses. A space mission to a black hole finds that another ship has arrived earlier: The Cygnus, which disappeared 20 years earlier. The explorers go on board and discover that the entire crew of the Cygnus has disappeared, except for a Dr. Reinhardt (Maximilian Schell), who explains that he’s about to try a daring plunge into the hole. The visitors are not enchanted. But one of them (Anthony Perkins) gets caught up in Reinhart’s mad vision, and a journalist (Ernest Borgnine) wanders about the gigantic Cygnus and discovers a great deal more than meets the eye. And then Reinhardt turns mean.

“The Black Hole,” meanwhile, revolves in outer space and is glimpsed from time to time through portholes. Physics is not my best subject, but I somehow doubt that we could see a black hole actually revolving, and my objection comes in two parts: I don’t think we could see the hole at all, and it would certainly not be revolving at the approximate rate of a ferris wheel.

No matter. The movie stays mostly inside the Cygnus, which resembles the spaceships in “Alien“ and ‘Star Trek’ in one key feature: Although the cost of launching and maintaining a space vehicle is incredibly expensive and every square foot counts, the Cygnus is as spacious as a country manor, with long hallways, high ceilings and vast command decks.

Why all the extra, empty interior space? Perhaps to give the special effects artists their opportunity to go berserk on the visuals. “The Black Hole” was designed by the veteran effects artist Peter Ellenshaw, who avoids the look of most earlier movie spaceships (wall-to-wall computer display screens re- laying meaningless information to non-existent monitors). Instead, his interiors consist of orderly patterns of basic colors, arrayed on control panels.

And then there is a vast porthole looking out into space, much as Capt. Nemo’s giant porthole surveyed the ocean in Ellenshaw’s designs for “20,000 Leagues Under the Sea.” The Cygnus, indeed, looks more like a fanciful space vehicle for a Nemo than like the fashionable High Tech so beloved in most movie spaceships. It’s inhabited by a crew that’s borrowed from gothic thrillers and “Star Wars.” There are strange, hooded, zombie-like figures that mope about all over the place. And then there are robots.

The friendly robot looks like C3PO, from “Star Wars,” and chirps out plucky little sayings while revolving its beady little eyes. The taller robots are ripped off from Darth Vader. And when everybody gets in a shootout, we’re left for the umpteenth time with the reflection that gunfights would surely be obsolete in outer space. (Can you imagine a technology that could venture to the edge of a black hole, and yet equip its voyagers with sidearms that inflict only flesh wounds?)

The basic problem with “The Black Hole” is that it doesn’t really confront the challenge of being a fiction about a black hole. The black hole is there, all right; and the characters gaze into it and make solemn statements, and Maximilian Schell seems properly obsessed with it, but we don’t feel a sense of wonder. There’s no awe. The hole’s a gimmick that the movie can cut away to, in between onboard plotting and scheming, and at the movie’s end there is a sensational visual payoff. But somehow it comes too late: The events leading up to it have been so trivial and cliche-ridden that the movie doesn’t earn its climax. And so whaddaya know? Black holes retain their reputations: Nothing can escape from them, not even this movie.