There aren’t a whole lot of dyed-in-the-wool art movies that take North American history, let alone United States history, as their topics and/or inspirations. Sure, there is a fair amount of Distinguished Cinema that does so, as in Merchant/Ivory’s “Jefferson In Paris“ to name a more palatable example or Roger Michell’s “Hyde Park On Hudson” to name a more indigestible one. But a movie of grand and enigmatic dimensions, with stunning visuals and an oblique approach to narrative? The most outstanding example I can recollect at the moment is Terrence Malick’s 2005 “The New World,” a retelling of the Pocahontas/John Smith affair in the form of an ecstatic meditation on nature and its corruption.

This movie is another, and possibly more unlikely example. It opens with a quote from Abraham Lincoln: “All that I am, or hope to be, I owe to my angel mother.” What follows, in austere, stately widescreen black-and-white, are views of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington D.C.. Then come more ecstatic, free-form, sunlight-dappled shots of a forest; a gritty-voiced narrator asks, “You wanna know what kinda boy he was?”

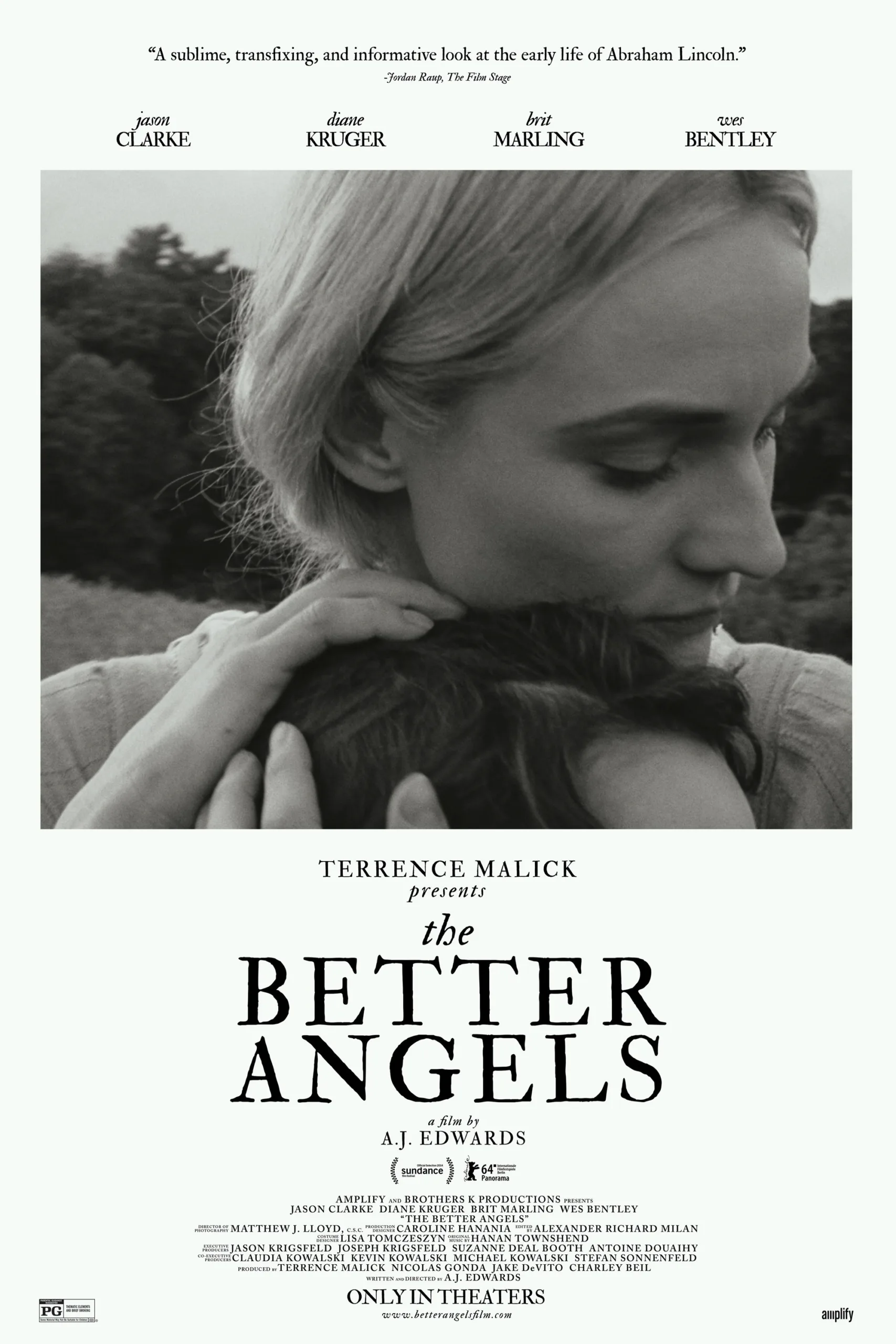

“The Better Angels” would feel under the influence of Malick even if the viewer were completely unaware of the fact that its director, A.J. Edwards, was Malick’s editor on “To The Wonder,” and that Malick executive-produced this film. The low-angle shots with the sunlight shining through trees as a buoyant human figure enters the frame from the right side, with Bruckner or Wagner or Dvorak music on the soundtrack; this is the sort of thing one associates with Malick. Edwards also applies a sometimes jarring cutting style, sometimes jumping frames within a single shot so that the old-time feeling of the rustic setting and characters is imbued with a you-are-watching-a-film apprehensive awareness. It’s all very beautiful, and certainly evocative of a kind of Primal American Feeling.

“But what’s the damn thing about?” I can hear some of you asking about now, and that’s where there’s a sticking point. As suggested by the opening epigraph, the depiction of the Lincoln Memorial, the loaded question of the movie’s first spoken words, and of course by the title, there’s something to do with Abraham Lincoln. More than something, as it happens; it’s a story of young Lincoln’s life, not “young” as in John Ford young, but young as in not even ten years old. The movie is set in the period in which Lincoln’s family moved from Kentucky to Indiana, a period that also saw a tentative beginning to Lincoln’s schooling and ended in a tragedy that readers familiar with their Lincoln history will know right away but the reveal of which here, in the context of this film review, would constitute—oh, the indignity of it all!—a spoiler.

Or would it? To tell you the truth, “The Better Angels,” as pictorially beautiful and emotionally evocative as it is, is so bereft of conventional narrative momentum that you have to consider it a miracle it got made. While its simulation of a pocket of past life is appropriately austere, and very beautiful, its story sense is such that it makes Bresson’s “Four Nights Of A Dreamer” look like “The Kennel Murder Case.” The minimalist dialogue contains questions such as “Where’s your spirit? How do you know it’s there?” and that’s in keeping with a certain inchoate Transcendentalist philosophy the movie’s perspective seems to strive for, but seekers of a meat-and-potatoes Lincoln story are likely to find the enterprise frustrating, manly gestures of Jason Clarke as Lincoln’s dad notwithstanding. (Brit Marling plays Lincoln’s mother, and succeeds in making the viewer unaware of her indie-it-person status.) There’s much to admire in this genuine American art film, but in some respects the things that are most daring about it wind up undermining its mission.