I’m not one of those reviewers who likes a particular type of Coen Brothers movie more than another. As much as I revered the filmmakers’ knotty, relatively somber “Inside Llewyn Davis,” I didn’t sit through “Hail Caesar” grumbling that I’d have preferred a more serious work.

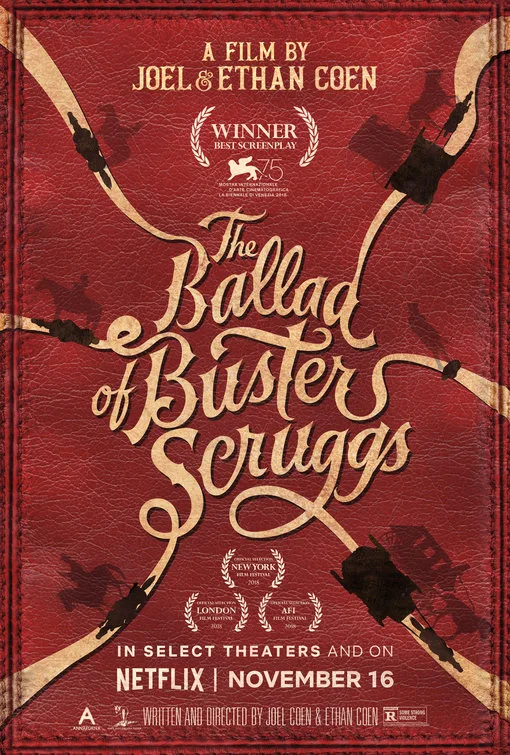

It’s hard to pin down the brothers’ new film, “The Ballad of Buster Scruggs,” an anthology film that presents itself as a literal story book, first edition 1873. As the mournful air that supports the ballad “Streets of Laredo” (and other lyrics, as the movie demonstrates in its last story) plays, the book opens, the pages turn; a full-page illustration shows a moment from a tense poker game; and away we go.

Into a rather goofy singing-cowboy vignette, the title story, starring Tim Blake Nelson as a man in a white hat who addresses the viewer most cheerfully before he begins blowing holes in any number of dirtier men who won’t cooperate with him. Is he, as a wanted poster paints him, a “misanthrope?” No, he insists, he just doesn’t like to be, um, contradicted.

This episode is a gasp-inducing wonder, a perfect storm of Frank Tashlin and Sam Peckinpah stylings, suggesting this is going to be one of the more raucous and absurdist Coen outings. The next story, starring James Franco as an ill-fated bank robber, leads up to a punchline that’s one of the funniest in the Coen canon.

In the third story, “Meal Ticket,” the movie takes a grim, mean turn. Its protagonists are a taciturn, hard-drinking traveling showman, Liam Neeson, and his charge, an armless and legless young man with a great store of poetry and scripture at his command, billed as a great “Orator.” Beginning his “set” every night with Shelley’s “Ozymandias,” he speaks to ever-dwindling frontier audiences, compelling Neeson to make an arguably ruthless business decision.

In “All Gold Canyon,” inspired by a Jack London story, Tom Waits—who fits so well into Coen World that it’s kind of a shock to realize this is his first picture with the filmmakers—plays a prospector for whom process seems more fulfilling than the accumulation of wealth. The next story, “The Gal Who Got Rattled,” featuring remarkable performances from Zoe Kazan, Bill Heck, and Grainger Hines, is also an adaptation, from a story by Stewart Edward White, but the Coens stack it with mordant ironies that not only make it their own, but make it perhaps the saddest of the tales here.

There’s a lot of killing in this movie, and many of those who suffer it are depicted lying down, with their eyes open, looking at the sky. In the movie’s final story, “The Mortal Remains,” one of a pair of bounty hunters, played by Jonjo O’Neill, tells his fellow passengers in a stagecoach of how, after his partner (Brendan Gleeson) has “thumped” one of their victims, he enjoys looking into that man’s eyes and watching as he negotiates the border between life and death, trying to find a state to which he can be reconciled. Do any of them “make it?” one of the passengers asks. “I don’t know,” the bounty hunter says cheerfully. “I’m only watching.”

This final segment plays like an extra-morbid but enigmatic coda to the prior proceedings. Then it hits you how, in a speech by Saul Rubinek’s “Frenchman” character (who introduces his philosophy of life by anticipating Sartre’s statement that “we have only this life to live”), his insistence that in life you “cannot play another man’s hand” completes a circle: extending the movie’s trajectory back into an animating situation in its first story.

What’s most bewitching throughout “Scruggs” is its sense of detail. Its meshing of formal discipline and screwed-down content sometimes give it the sense of a work that has been carefully and elaborately embroidered rather than photographed.

Do the Coens troll their audience? Yes and no. Movies require too much money and effort to predicate them merely on pranking people you don’t like. On the other hand, I had a conversation last fall with a great film scholar and critic who rather famously dislikes the Coens’ work, and he was taking issue with the naming of the main character and ostensible hero of “Hail Caesar.” Josh Brolin’s good guy “Eddie Mannix” was named for a real-life character who was in fact a rather bad guy, an MGM-employed “fixer” who covered up major crimes by film figures and bullied potentially rebellious stars into doing the studio’s will. “Why would they want to ennoble Eddie Mannix,” he asked, and I said that, clearly, the movie wasn’t intended as any kind of portrait of the real Eddie Mannix, and that they probably just liked the name. Which I think is true. But the Coens are creators who rather effortlessly work on multiple levels, and I think it’s closer to the truth to say that they liked the name AND that they knew that using it would push certain people’s buttons, and they’re not just fine with that; they’re delighted by it.

Here, their adaptation of Western story modes goes directly against contemporary consciousness of Native American genocide and other issues. Because it’s a pastiche, it situates itself in an old-fashioned mode in which diversity is articulated only in terms of mutual antagonism. The only articulation of a Native American perspective comes in the form of a disdainful laugh one “Indian” warrior throws in the direction of a character with a noose around his neck. For the purposes of this marvelous and disquieting movie, it’s enough. Its pleasures—the endless succession of perfect shots of remarkable scenery, the gorgeous music by Carter Burwell and others that swells and dips like the landscapes themselves—are real, and acknowledged as such, but there’s something more real underneath it all. The book’s pages at the movie’s beginning are turned too quickly for a viewer without a freeze button to read its dedication and epigraph, but the latter might as well be a portion of the Russian grammar book sample Vladimir Nabokov used to open his 1952 novel The Gift, to wit, “An oak is a tree. A rose is a flower. A deer is an animal. A sparrow is a bird. Death is inevitable.”