France in the winter of 1942-43 is in the grip of the Nazi occupation, and for most Parisians there is little food, heat or joy.

But for a few, like the opera singer Irene Brice and her husband, Charles – who will do business with anyone – life is still a giddy whirl of parties, receptions, recitals, all launched from the stage of their luxurious apartment.

For Sophie Vasseur, a young pianist who lives with her mother in desperate poverty, such a life is beyond her dreams, until she is hired to accompany Mrs. Brice, and is swept into her opulent sphere.

Yet all is not as it seems, even there, and the quiet, almost mousy girl finds that in the shadows of Irene’s brilliance she can sit unnoticed, and see everything.

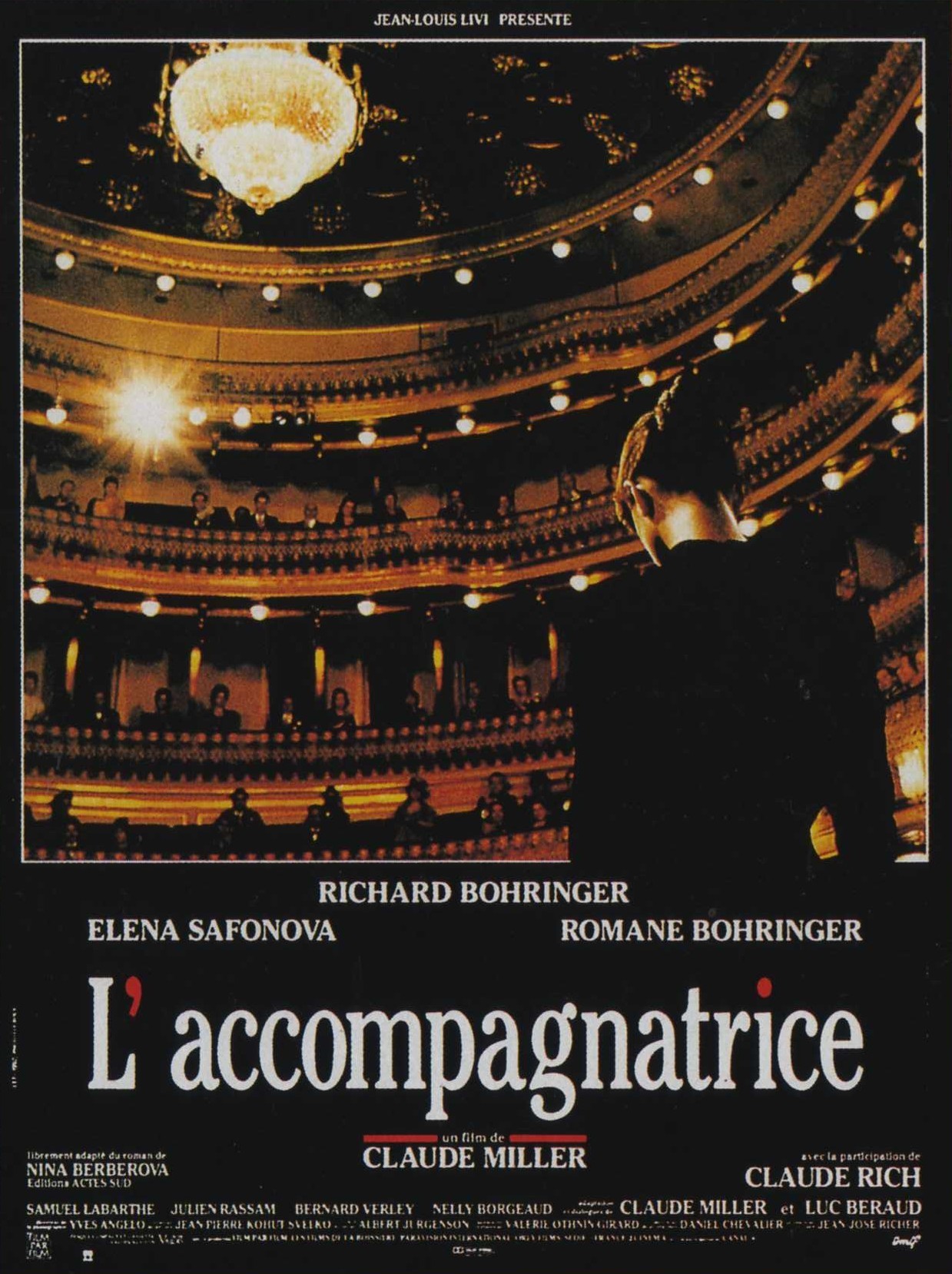

What she sees, and what she thinks about it, are what make Claude Miller’s “The Accompanist” so absorbing. This is not a film about greedy French collaborationists, nor is it a remake of “All About Eve,” although for a time it seems to be heading in the direction of that mocking story about the understudy who replaces her patroness. No, it is more about how nothing is as simple as it seems; about how people will do much to assure their comfort and success, but there are some things that some people will not do.

The relationship between Sophie (Romane Bohringer) and Irene (Elena Safonova) is easily grasped. At first we think it cannot be as simple as it seems, but apparently it is: Irene is a generous, friendly woman who wants her accompanist with her at all times, and so makes her at home in a world of luxury. Sophie’s visits to her mother’s cold, barren flat are not frequent; at the Brices’, she may be an employee but is treated like one of the family.

If she is grateful for this treatment, she also has complex feelings about Irene, who is beautiful, gracious, talented, and always seems to know the right way to handle any situation. Sophie believes, with some reason, that she is none of those things. She is a very good pianist, but that is taken for granted. And so behind her big open eyes, thoughts form, and we begin to guess what they are. We may, however, not be correct.

The key to the Brice household is the extraordinary energy and almost arrogant self-confidence of Charles Brice (played by Richard Bohringer, Romane’s father). He likes luxury. He demands the best. It costs a lot, and he works hard to make money, which is easy in wartime Paris if you will deal with the Nazis and more or less impossible if you won’t. Yet, there is a quirk in him. He will not kiss their boots. He will even insult them to their faces, and because they need him they will let him go almost too far (there is a trace of Oskar Schindler here).

Sophie, who sees everything, begins to realize that Irene is having an affair with a handsome young man who is active in the Resistance. Sophie runs errands she is not supposed to understand, but she does. She follows her employer. She begins to understand the nature of the affair. In Paris in the 1940s, it is, of course, not unheard of for married people to have affairs, but still – for Irene to be married to a collaborationist and to be sleeping with a member of the Resistance. . . .

Here, too, the movie surprises us. There is none of the clear-cut “Casablanca” ethic at work. In the real world, not everyone in the Resistance is perfect, and not everyone in Charles Brice’s position is irredeemable. There comes a time when Charles realizes, decisively, that it is time for them all to get out of France, and he acts swiftly; like all true entrepreneurs, he is a gambler, willing to be a rich man one day and a refugee the next. After a journey on which they are nearly killed, they arrive in London, where . . .

Our attention is on Sophie during all of this. She has learned and grown. She does not make the same mistake twice. She loves Irene, resents her, and feels competitive with her in ways Irene does not suspect. And when Sophie has a shipboard romance with an almost insufferably idealistic young man, there comes a time when she must choose between her lover and her employer, and . . .

It is all so complicated. That is the joy of it. This movie offers no quick Hollywood solutions in which the good and evil characters are clearly identified. There is no parceling out of blame and praise at the end. Perhaps Miller is telling a parable, and Sophie is Vichy France, coexisting with collaborators to survive, yet remaining watchful and aloof. Perhaps he is simply telling a story, in which Sophie decides not to force a dramatic change because it is more interesting, and certainly more comfortable, to stay on board for the ride.

The performances require our close attention. All three are very complex. A lot is going on. If Irene is more or less consistent and Sophie remains an enigma, Charles is fascinating because he acts decisively in ways we can understand. In the background, the world is at war. Charles tries to make a separate peace, not so much with the warring parties as with himself. The movie asks if this is possible.

Its title perhaps means more than at first it seems.