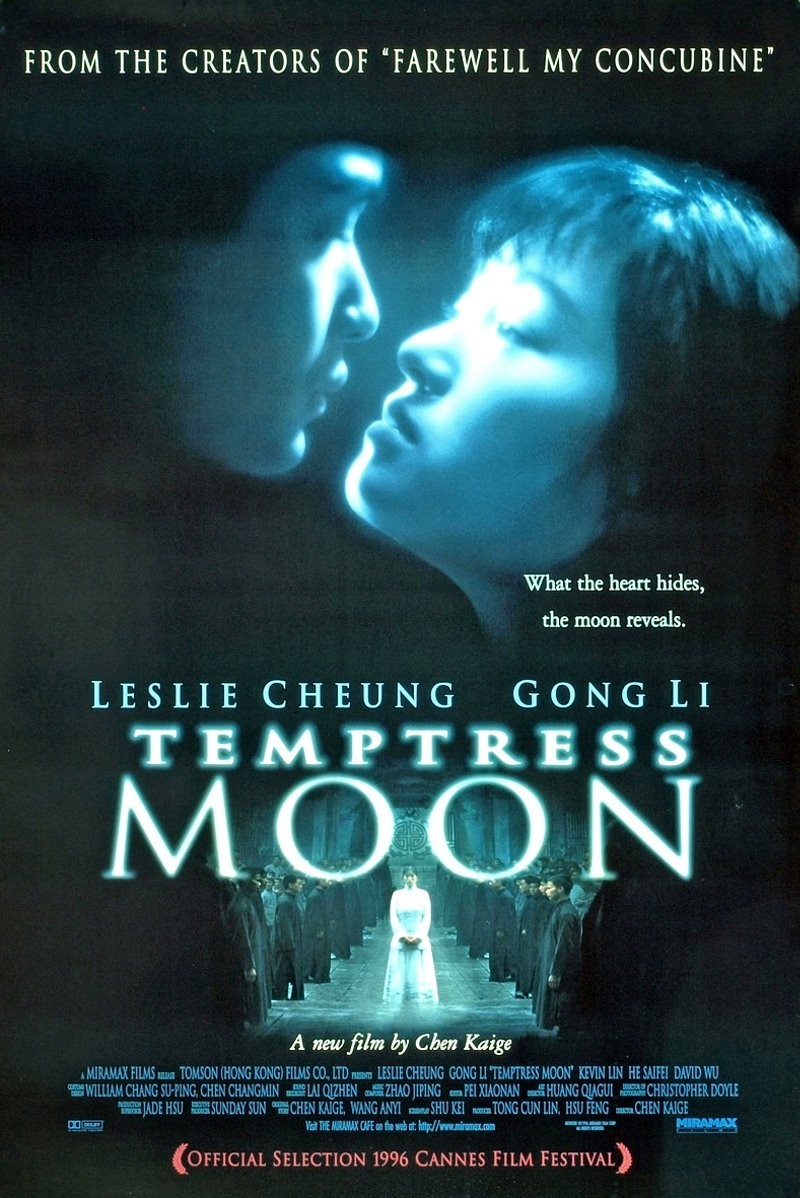

Chen Kaige’s “Temptress Moon” opens like one of those 19th century novels with a cast of characters on the first page. In a helpful sequence added by Miramax, the film’s U.S. distributor, we are introduced to the three central characters, first as children, then as adults, with their names printed on the screen under their faces. There is also a prologue, which scrolls up the screen as it is read aloud.

This is not window-dressing. “Temptress Moon” is a hard movie to follow–so hard, that at some point you may be tempted to abandon the effort and simply enjoy the elegant visuals by the Australian cinematographer Christopher Doyle, who mirrors the labyrinthine story with his treatment of city streets and shadowed corridors, all circling back upon themselves.

Like almost all modern Chinese films, this one is ravishing to look at, but it is impossible to care deeply about, because Kaige’s characters, once we have them straight, are not sympathetic or even very interesting. I found myself more absorbed in the backgrounds and contexts of the action–in the ceremony, for example, by which a family aide informs its members of a change of leadership.

The story centers on Zhongliang (Leslie Cheung), who as a boy was raised on the decadent country estate of the Pang family, where his playmate was Ruyi (Gong Li). Now follow this closely. In 1911, the family is headed by Old Master Pang. His son, Zhengda (Zhou Yemang), is married to Xiuyi (He Saifei), who is Zhongliang’s sister–which is why Zhongliang is invited there in the first place. (Ruyi is Zhengda’s sister.) Zhongliang’s duties include preparing the opium pipes for the Pangs, father and son, and for his own sister. There is a murky flashback later in the film indicating that Zhengda forced Zhongliang to kiss Xiuyi–and there are shadowy implications of additional incest.

Whatever. Time passes. Zhongliang flees, eventually finding work in Shanghai as a gigolo who kisses women while stealing their pearls. Old Master Pang dies. Young Master Pang (Zhengda) becomes a witless basket case through opium addiction, and so Zhengda’s sister, Ruyi, is made the acting head of the family. Knowing that Ruyi and Zhongliang were playmates as children, Zhongliang’s criminal boss orders him back to the Pang estate, where the scenario is that he will use his skills as a gigolo to seduce Ruyi and gain control of the family’s assets.

Ruyi is envisioned as a sort of caretaker until a suitable male heir can be groomed, but she seizes firm control immediately, and orders her late father’s concubines out of the house (everyone is scandalized; surely they deserve a serene retirement?). But Ruyi is also addicted to opium, and the entire family seems bemused by its fumes.

Why do I feel as if I’m sitting in an opera house, trying to absorb the convoluted synopsis before the curtain goes up? Somehow it seems as if Kaige could have covered the essential elements of his story with fewer characters, especially since the flashbacks mean that the key characters are played both by children and adults, further complicating things.

Bewildered, I turned to the Web to see what Asian critics of the film had written, and was relieved to find I was not alone: “This dazed and confused viewer found it hard to make out what the story was about” (S. Young, Singapore). “He has to be ambiguous and obscure. The man has a thing or two to say. You bet. But he [doesn’t] say it straight. He has to say something by not saying it, say something that has something else inside it, or say one thing and mean another” (Long Tin, Hong Kong).

The film is, in any event, beautiful to behold–as is Gong Li, although by making her an opium addict Kaige requires her to be unfocused and addled, and that undercuts the intelligence that is key to her beauty.

The film and its director ran into difficulties with the Chinese government, as did Kaige’s “Farewell My Concubine” (1993), which also starred Gong Li and Leslie Cheung. The earlier film depicted homosexuality and suicide, which were frowned upon. I am not sure why “Temptress Moon” got into trouble. It presumably wouldn’t concern the current regime that the 1920s are portrayed as a period of decadent capitalist excess, but I suspect there is a level of allegory in the story that eludes me. The film opens with the abdication of the old emperor in 1911; could we move the entire action forward to the death of Mao and decode the symbolism? You tell me.