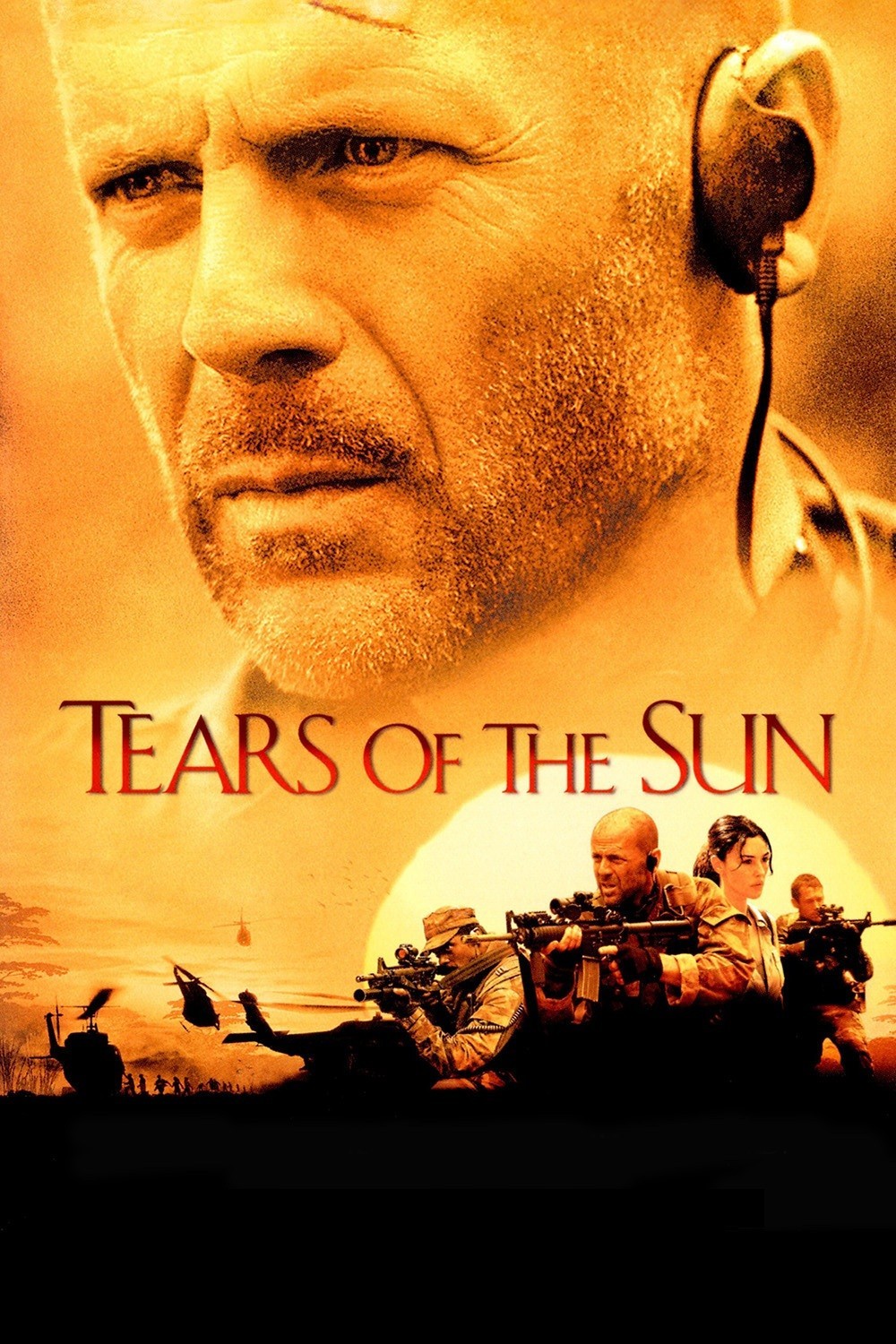

“Tears of the Sun” is a film constructed out of rain, cinematography and the face of Bruce Willis. These materials are sufficient to build a film almost as good as if there had been a better screenplay. In a case like this, the editor often deserves the credit, for concealing what is not there with the power of what remains.

The movie tells the story of a Navy Seals unit that is dropped into a Nigerian civil war zone to airlift four U.S. nationals to safety. They all work at the same mission hospital. The priest and two nuns refuse to leave. The doctor, widow of an American, is also hostile at first (“Get those guns out of my operating room!”), but then she agrees to be saved if she can also bring her patients. She cannot. There is no room on the helicopters for them and finally Lieut. Waters (Bruce Willis) wrestles her aboard.

But then he surprises himself. As the chopper circles back over the scene, they see areas already set afire by arriving rebel troops. He cannot quite meet the eyes of the woman, Dr. Lena Hendricks (Monica Bellucci). “Let’s turn it around,” Willis says. They land, gather about 20 patients who are well enough to walk, and call for the helicopters to return.

But he has disobeyed direct orders, his superior will not risk the choppers, and they will all have to walk through the jungle to Cameroon to be rescued. Later, when it is clear Willis’ decision has placed his men and mission in jeopardy, one of his men asks, “Why’d you turn it around?” He replies: “When I figure that out, I’ll let you know.” And later: “It’s been so long since I’ve done a good thing–the right thing.” There are some actors who couldn’t say that dialogue without risking laughter from the audience. Willis is not one of them. His face smeared with camouflage and glistening with rain, his features as shadowed as Marlon Brando’s in “Apocalypse Now,” he seems like a dark violent spirit sent to rescue them from one hell, only to lead them into another. If we could fully understand how he does what he does, we would know a great deal about why some actors can carry a role that would destroy others. Casting directors must spend a lot of time thinking about this.

The story is very simple, really. Willis and his men must lead the doctor and her patients through the jungle to safety. Rebel troops pursue them. It’s a question of who can walk faster or hide better; that’s why it’s annoying that Dr. Hendricks is constantly telling Waters, “My people have to rest!” Presumably (a) her African patients from this district have some experience at walking long distances through the jungle, and (b) she knows they are being chased by certain death, and can do the math.

Until it descends into mindless routine action in the climactic scenes, “Tears of the Sun” is essentially an impressionistic nightmare, directed by Antoine Fuqua, the director who emerged with the Denzel Washington cop picture “Training Day.” His cinematographers, Mauro Fiore and Keith Solomon, create a visual world of black-green saturated wetness, often at night, in which characters swim in and out of view as the face of Willis remains their implacable focus point. There are few words; Willis scarcely has 100 in the first hour. It’s all about the conflict between a trained professional soldier and his feelings. There is a subtext of attraction between the soldier and the woman doctor (who goes through the entire film without thinking to button the top of her blouse), but it is wisely left as a subtext.

This film, in this way, from beginning to end, might have really amounted to something. I intuit “input” from producers, studio executives, story consultants and the like, who found it their duty to dumb it down by cobbling together a conventional action climax. The last half hour of “Tears of the Sun,” with its routine gun battles, explosions, machine-gun bursts, is made from off-the-shelf elements. If we can see this sort of close combat done well in a film that is really about it, like Mel Gibson’s “We Were Soldiers,” why do we have to see it done merely competently, in a movie that is not really about it? Where the screenplay originally intended to go, I cannot say, but it’s my guess that at an earlier stage it was more thoughtful and sad, more accepting of the hopelessness of the situation in Africa, where “civil war” has become the polite term for genocide. The movie knows a lot about Africa, lets us see that, then has to pretend it doesn’t.

Willis, for example, has a scene in the movie where, as a woman approaches a river, he emerges suddenly from beneath the water to grab her, silence her, and tell her he will not hurt her. This scene is laughable, but effective, Laughable, because (a) hiding under the water and breathing through a reed, how can the character know the woman will approach the river at precisely that point? and (b) since he will have to spend the entire mission in the same clothes, is it wise to soak all of his gear when staying dry is an alternative? Yet his face, so fearsome in camouflage, provides him with a sensational entrance and the movie with a sharp shudder of surprise. There is a way in which movies like “Tears of the Sun” can be enjoyed for their very texture. For the few words Willis uses, and the way he uses them. For the intelligence of the woman doctor, whose agenda is not the same as his. For the camaraderie of the Navy Seal unit, which follows its leader even when he follows his conscience instead of orders. For the way the editor, Conrad Buff, creates a minimalist mood in setup scenes of terse understatement; he doesn’t hurry, he doesn’t linger. If only the filmmakers had been allowed to follow the movie where it wanted to go–into some existential heart of darkness, I suspect–instead of detouring into the suburbs of safe Hollywood convention.