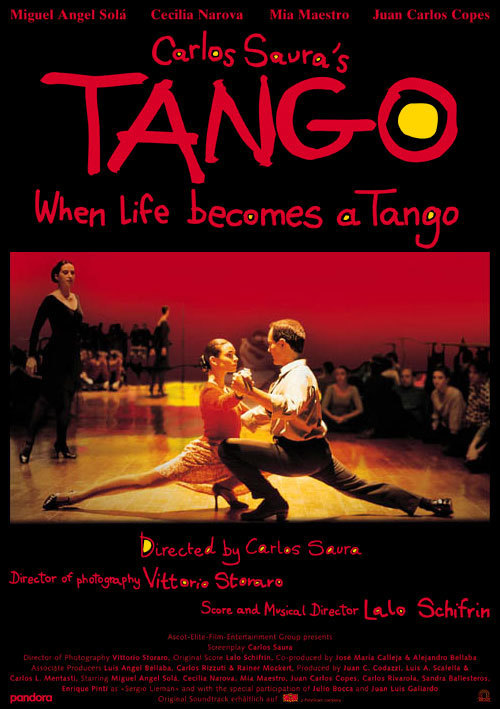

The tango is based on suspicion, sex and insincerity. It is not a dance for virgins. It is for the wounded and the wary. The opening shots of Carlos Saura‘s “Tango,” after a slow pan across Buenos Aires, are of a man who has given his life to the dance and has a bad leg and a walking stick as his reward. This is the weary, graceful Mario (Miguel Angel Sola), who is preparing a new show based on the tango.

At the same time, perhaps Mario also represents Carlos Saura. The movie, one of this year’s Oscar nominees, has many layers: It is a film about the making of a film, and also a film about the making of a stage production. We are never quite sure what is intended as real and what is part of the stage production. That’s especially true of some of the dance visuals, which use mirrors, special effects, trick lighting and silhouettes so that we can’t tell if we’re looking at the real dancers or their reflections. A special set was constructed to shoot the film in this way, and the photography, by the great three-time Oscar winner Vittorio Storaro, is like a celebration of his gift.

If the film is visually beautiful, it is also ravishing as a musical–which is really what it is, with its passionate music and angry dance sequences. It is said the musical is dead, but it lives here, and Saura of course has made several films where music is crucial to the weave of the story; his credits include “Blood Wedding,” “Carmen” and “Flamenco.” Early in the film, Mario visits a club run by the sinister Angelo Larroca (Juan Luis Galiardo), who asks him a favor: an audition for his girlfriend Elena (Mia Maestro). Mario can hardly refuse, because Angelo has owns 50 percent of the show. Mario watches Elena dance and realizes she is very good. He begins to fall in love with her, which is dangerous; when he makes a guarded proposal at dinner, she says, “Come off it–you know who I’m living with!” Yes, he does. So does his estranged wife, Laura (Cecilia Narova), who warns him off the girl. But Mario and Elena draw closer, until finally they are sleeping with each other even though Angelo has threatened to punish cheating with death. What adds an additional element to their romance is Mario’s essential sadness; he is like a man who has given up hope of being happy, and at one point he calls himself “a solitary animal–one of those old lions who roams the African savanna.” Of course, there is always the question of how much of this story is real and how much is the story of the stage production. Saura allows us to see his cameras at times, suggesting that what we see is being filmed–for this film? Back and forth flow the lines of possibility and reality.

There are several dance sequences of special power. One is an almost vicious duet between Elena and Laura. Another uses dancers as soldiers and suggests the time in Argentina’s history when many people disappeared forever. That time is also evoked by images of startling simplicity: Torture, for example, is suggested by light on a single chair. And there is also a sequence, showing mostly just feet and legs, that suggests the arrival of immigrants to Argentina. You see in “Tango” that there are still things to be discovered about how dancing can be shown on the screen.

Recently, for one reason or another, I’ve seen a lot of tango. A stage performance in Paris, for example, and the 1997 British movie “The Tango Lesson.” Apart from the larger dimensions of the dance, there is the bottom line of technical skill. The legs of the dancers move so swiftly and so close to each other that only long practice and perfect timing prevent falls–even injuries. With the tango you never get the feeling the dancers have just met. They have a long history together, and not necessarily a happy one; they dance as a challenge, a boast, a taunt, a sexual put-down. It is the one dance where the woman gives as good as she gets, and the sexes are equal.

The romantic stories in “Tango” reflect that kind of dynamic. Mario and his estranged wife talk the way tango dancers dance. The early stages of Mario’s seduction of Elena are like an emotional duel. The role of Angelo, the tough guy, is like a stage tango performance when a stranger arrives and tries to take command. It isn’t real. It is real. It’s all rehearsed, but they really mean it. It’s only a show, but it reflects what’s going on in the dancers’ lives. It’s only a dance. Yes, but life is only a dance.