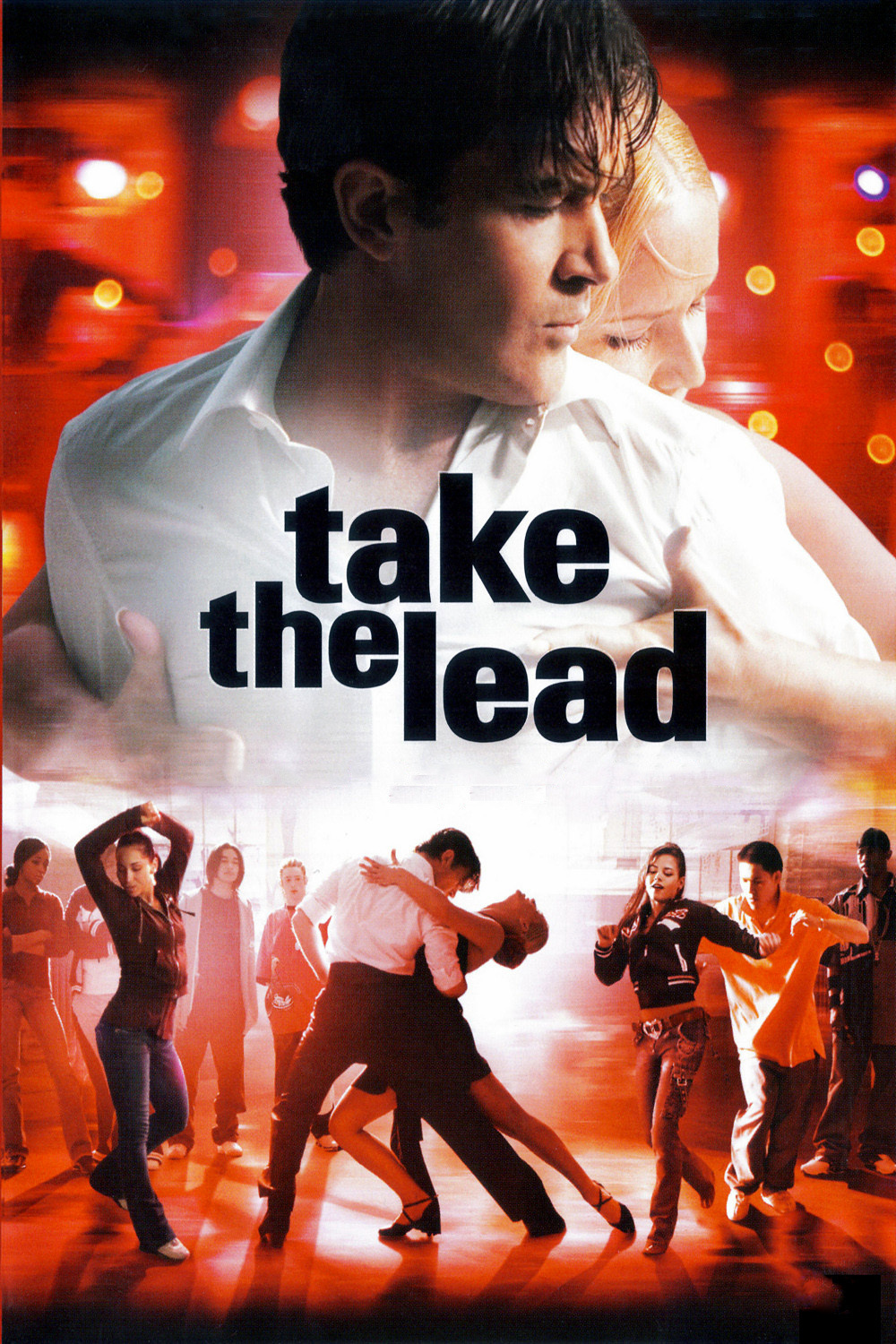

“Take the Lead” begins with rudeness, ends with good manners, and argues that poor inner city schools can be redeemed by ballroom dancing. The only thing wrong with this vision, I suspect, is that it works for the ballroom dancers but not for the gangbangers, who continue on their chosen careers. There is a more pessimistic view of urban high schools in another movie opening today, “American Gun,” and I fear it’s closer to the truth.

But “Take the Lead” is said to be based on a true story, it tells a heartening fable, and Antonio Banderas is uncommonly charming as a dance teacher who walks into a high school and announces that he will improve it by his very example.

Public manners have degenerated in recent decades. It is now routine to hear obscenities shouted in public, and by all sorts of people, not just in traffic but even in Starbucks. I am as fond of colorful language as anyone, but I try not to inflict it upon strangers. I suspect many people sense they should have better manners, and need only a nudge. In high school, I was addressed for the first time in my life as “Mister Ebert” by Stanley Hynes, an English teacher, and his formality transformed his classroom into a place where a certain courtliness prevailed.

In “Take the Lead,” Banderas plays Pierre Dulaine, a Manhattan ballroom dancing instructor who rides the streets, impeccably dressed, on his bicycle. One day, he witnesses a student named Rock (Rob Brown) attacking a teacher’s car with a golf club. Rock has his reasons, but never mind; instead of calling the cops, Dulaine walks into the school the next day and announces to the principal (Alfre Woodard) that he wants to teach ballroom dancing to the detention class.

She is a take-charge realist who walks the hallways ordering students to take off their hats, pull up their pants and remove their hands from the netherlands of others, and her impulse is to laugh at Pierre, or throw him out. But he prevails and walks into the detention hall, where the students regard him as a visitor from the moon. They resist him, but he fascinates them, especially when he brings in one of his sexiest ballroom colleagues to show them what is surely true, that the tango is more manly, more feminine, more sexy and more plain damn hot than any other form of motion requiring clothes.

Having seen the charming documentary “Mad Hot Ballroom” (2005) about New York grade school kids learning to dance, I anticipated the general direction of “Take the Lead.” It is not a particularly original movie and lacks the impact of such earlier classroom parables as “Stand and Deliver,” “Lean on Me,” “Mr. Holland's Opus” and the similar “Music of the Heart.” The vulgar, rebellious, resentful, potentially criminal students are transformed by dancing as surely as music transforms the hero of “Hustle & Flow.” And of course the film ends in a ballroom dancing competition, with full-court choreography that in real life takes weeks of rehearsal but in the movies springs spontaneously from the souls of the dancers.

The film is more fable than record, and more wishful thinking than a plan of action. Yet the end credits leave me no doubt that the real Pierre Dulaine’s programs have spread to many other schools and that thousands of students are now learning the tango, the fox-trot and other dances that are taught with so much less effect in another movie opening today, “Marilyn Hotchkiss' Ballroom Dancing and Charm School.” Strange, how movies can open simultaneously and cast light on each other.

Still, I felt the Alfre Woodard character had something to be said for her dubious realism (the high school principal played by Forest Whitaker in “American Gun” would certainly agree with her) and that the ascendancy of Pierre Dulaine was a little too smooth. I began to suspect he drew a good hand in that detention class, which is made of basically good and misunderstood kids. One really hard case might have capsized the ship.

That said, Antonio Banderas is reason enough to see the movie. There are some people who by their personal style can make us want to be better. “Whenever you’re in doubt in a social situation,” the director Gregory Nava once assured me, “just ask yourself, what would Fred Astaire do?”

Pierre Dulaine must ask himself this question several times a day. He dresses well, carries himself with grace and self-respect, treats everyone politely and all but shames them into returning his courtesy. By being so resplendent in his bearing and effect, he generates envy: The kids follow him not because they want to improve and reform, but because they would like to be that cool.