The documentarian Rory Kennedy is known for making pictures about very serious topics. The titles alone tell the story: “Pandemic: Facing AIDS,” “Ghost of Abu Ghraib,” “Last Days in Vietnam.” This, pop culture semiotics observers and others might note, is fitting work for a Kennedy kid—Rory is the youngest child of Robert F. and Ethel Kennedy.

It seems a little uncharacteristic that her latest movie is about a surfer. However, it’s clear from the opening montage that Laird Hamilton is not a fun, laid-back, carefree surfer. Prior movies about surfers and surfing, from “Endless Summer” and “Big Wednesday” on, do create portraits of catch-the-ultimate-wave obsessiveness, but they also have some emphasis on good times—sun, sand, girls, beer, bonfires. You don’t get any of that here. Right off the bat, Hamilton is described as an “incorrigible egomaniac” who has “created problems that will never be solved.” If you didn’t think surfing could have problems, well, this movie will tell you.

Kennedy hews to standard bio-doc style in the first hour of the movie. Hamilton’s birth in the early ‘60s—his mom having been a surfer herself—is followed by the young family’s abandonment by the biological father. Hamilton’s adoptive dad was also part of the milieu, and he notes that Laird was “one of the last children who got to live and breath while the pioneers still surfed.” With his half-brother, Laird makes trouble in school—“Disobedient? He was completely disobedient,” his sibling says—and takes to the water, insisting that it “teaches you courage, fear, respect.”

Hamilton is an interesting case for many reasons. First, he’s never been a proper “professional” surfer. In early days, he used his good looks to work as a model, as one of his closest friends in the sport did, and he didn’t have the inclination to go through the games of auditions. Same with acting. Why didn’t he surf competitively? “I don’t think I rejected competition as much as judgment,” he tells Kennedy. But the kind of surfing he ended up excelling at invited, and still invites, a ton of judgment.

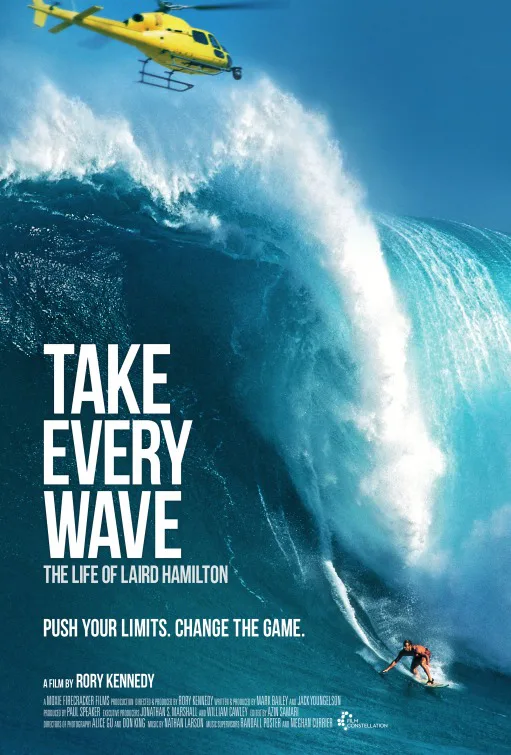

Laird Hamilton does big-wave surfing. With the assistance of a jet ski, which, as one commentator says, provides access toward “waves too big and too powerful to paddle out to,” he gets far enough out to hook on to waves 70, 80, 100 feet high. The footage of him in the water is awe-inspiring, as are a number of iconic photographs of Hamilton at work.

From an early age, Hamilton was attracted to physical challenges that sometimes seem out and out stupid rather than plainly risky. He and a pal recall a time when they paddled on surfboards from Italy’s mainland to Corsica, learning the hard way the difference between 37 nautical miles (which the distance actually was) and 37 kilometers (which they thought the distance was).

These days, Hamilton, now in his early 50’s but still in spectacular shape outwardly (a doctor informs him early in the film that a wobbly hip and other strains on the body will curtail his surfing activities in pretty short order), rhapsodizes without a hint of irony about how effects of climate change will create great conditions for what he does. “The potential to have giant waves this year, in this El Niño season, is great,” he says at one point. The movie examines how his possibly Ahab-esque pursuit has both wowed and annoyed the mainstream surfing world, and taken a toll on his relationships. As I implied, the surf world of Laird Hamilton isn’t big on “girls,” but there is one woman, Gabrielle Reece, who speaks frankly of the ups and downs of life with a guy like this. The volleyball player and model met Hamilton on a TV shoot in the ‘90s, as his first marriage was falling apart, and they set up a household together very shortly after that. She’s a sharply intelligent person who’s refreshingly matter-of-fact about her perspective. As is he.

So, no, this is not a frivolous film. There are a few surfing sequences that provide a rush of “whoa!” adrenaline, and some breathtaking Hawaiian landscapes on display. But the movie is a character study more than anything else. Hamilton’s drive, his near-tunnel-vision, resembles that of a kind of political crusader, and while Kennedy doesn’t draw the comparison directly, one can infer that this quality played a significant role in drawing the filmmaker to this subject.