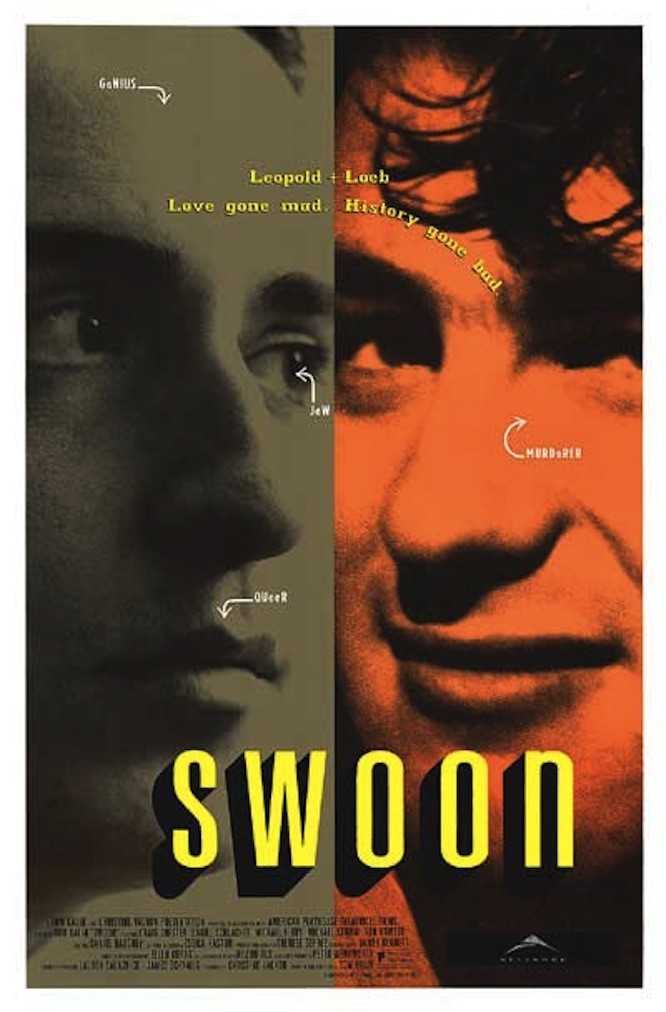

“Swoon” reopens once again the notorious thrill-killing of Bobby Frank, whose murder in the 1920s became an international scandal when it was revealed that two rich young Chicago homosexuals, Richard Loeb and Nathan Leopold Jr., had committed the crime. Their motives were chilling: They wanted to do it simply to prove to themselves that they were smart enough to get away with it. Leopold and Loeb escaped the death penalty only because of an impassioned defense by Clarence Darrow, the best-known defense attorney of his time, who argued they were insane, and used their homosexuality as proof of insanity.

The case has been made into two previous movies – Alfred Hitchcock’s “Rope” (1948) and Richard Fleisher’s “Compulsion” (1959), but both to one degree or another played down the topic of homosexuality. This new version by writer-director Tom Kalin plays it up, sometimes in ways that are fairly disturbing, as when he seems to linger on the ways the dominant Loeb was able to control the more submissive Leopold by using sex as a weapon.

The movie, shot in black and white, has the look of modern men’s fashion photography, and Kalin deliberately allows anachronistic props into the frame (a TV channel changer and a push-button phone, for example) to make the film’s reality level more ambiguous. This is a period picture that knows it is a period picture, and is also aware of later periods; there is no attempt to fix the story’s attitudes in the 1920s, and there is a subtle but unmistakable level of the film that addresses the killing in terms of sadomasochistic chic. The murder of Bobby Frank is seen not as a criminal act, but as a sexual adventure that got out of hand.

The question then becomes: How should one interpret the film? Kalin does not use the argument that society is to blame, that because homosexuality was outlawed, Leopold and Loeb were somehow forced into the lapse of sanity which led to the murder. There is every indication in the film that Loeb in particular enjoyed the whole event, not just the murder, but the way it demonstrated his power over Leopold; one imagines he would have been capable of the same crime in a more permissive era, or, for that matter, if he had not been homosexual at all. He is simply an evil person.

Leopold, on the other hand, is a weak one, whose relationship with Loeb is complex. Sex is a part of it. So is fear; he dreads losing the approval and friendship of this man he finds so attractive, and does what he does almost in a daze of need and apprehension. Later in a long life, he tried to redeem himself, in prison and on parole, and there was never the sense that he was as essentially evil as Loeb.

What is the movie trying to show us? The power of sexual control, for one thing; Loeb, who is depraved, is also highly intelligent, and everything he does seems almost like an exercise, to prove that he can do it. “Swoon” goes much deeper than the other studies of the Frank case, because it tries to show exactly how the psychosexual balance between the two killers made a murder possible, when neither Leopold nor Loeb could possibly have killed by himself.

Loeb was incapable of the act, and Leopold incapable of the desire.

This is the kind of movie that inspires discussion afterwards. It is being reviewed as an example of the new “queer cinema,” deliberately gay films by openly gay filmmakers, but I am not sure “Swoon” would have needed to be much different if the killers had been heterosexual lovers. I don’t think what they did resulted from the fact that they were gay; I believe similar acts throughout history, in tolerant times and repressive ones, have been committed by all kinds of people were born without what we call the conscience (as Loeb was) or without the courage to follow it (Leopold). It is probably true that more people fall in Leopold’s category than Loeb’s, which is why he has always drawn more sympathy from students of the case. It is easier and more reassuring to imagine being seduced into evil, than to imagine not even knowing what evil is.