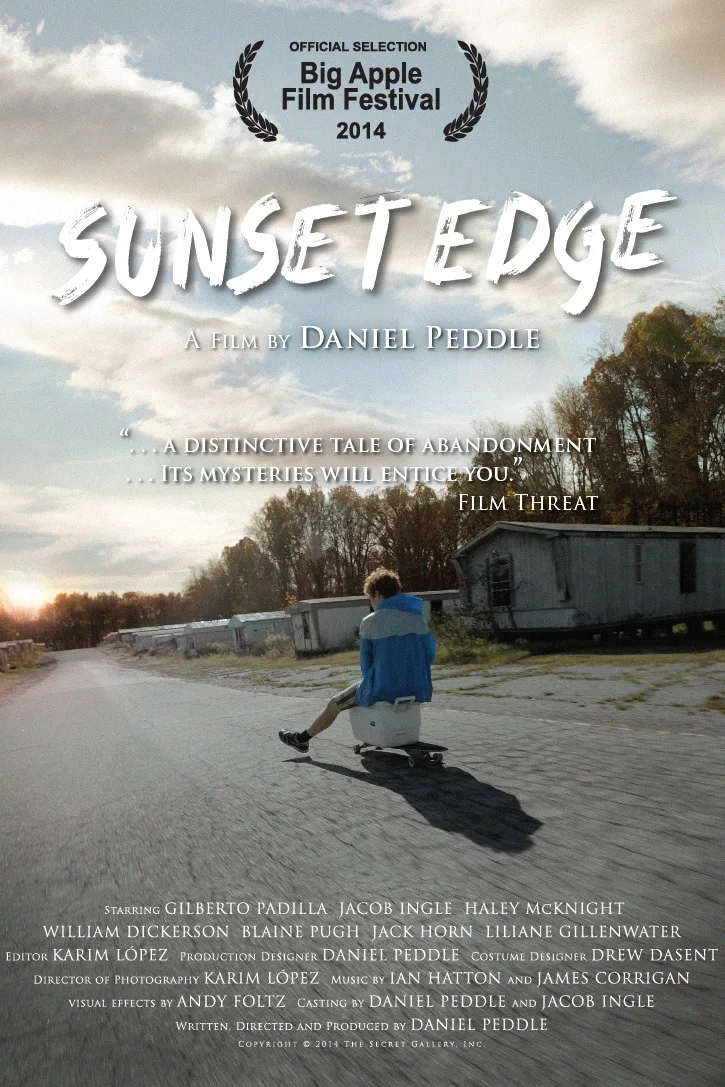

“Sunset Edge,” a coming-of-age drama that’s also Southern Gothic ghost story, is an unusual, ambitious failure, mostly because the film’s hyper-naturalistic style is meant to evoke a supernatural mood. We watch as emotionally withdrawn teenagers communicate with each other through negligible dialogue. And their lazy summer hijinks–taking selfies, drinking sugary soda, and exploring an abandoned trailer park–seem to have been filmed entirely in natural light. Hand-held cameras follow downcast young characters as they pore over abandoned furniture, musty photographs and other left-behind debris as if the film’s lead protagonists were the first people to navigate Pompeii’s ruins. “Sunset Edge” consequently presents its characters as adolescent sleepwalkers (though “adolescent” is redundant in this context). But despite its tantalizing central conceit, “Sunset Edge” is executed so listlessly that its creators often strain for significance that they never fully grasp.

“Sunset Edge” thrives on mystery, though it’s not atmospheric enough to be really mysterious. In theory, the film’s nesting doll plot structure is intriguing: the first story (plot A) gets going, then pauses while the second story (plot B) catches up to where the first left off. Plot A is like a kinder slasher movie scenario. A group of teenagers haunt the ruins of Sunset Edge, a dilapidated trailer park. These kids are so introverted and non-threatening that the longest conversation they have is a Socratic monologue about the group’s infinitely small place in the universe (apparently, they’re like a grain of sand on the beach!). They then wander around a little more. Time passes. One member of the group, Haley (Haley Ann McKnight), goes missing after photographing herself by a wood-lined clothesline. Then plot B kicks in, and we meet Malachi (Gilberto Padilla), the last of Sunset Edge’s living inhabitants.

Notice how little plot there is in that plot description. “Sunset Edge” is a mood piece, so much of your enjoyment of the film’s events depends on your interest in exploring the film’s decadent milieu. These kids solemnly tromp around unlit homes without doing any serious rummaging; they’re too respectful to rummage, they’re just poking around other people’s homes because they’re there, or something.

So these kids reverently explore the woods surrounding Sunset Edge, never getting too rowdy, never touching alcohol, never cursing, or horsing around too much. Then they’re joined by Malachi, a mysterious stranger who remembers how fraught his home life was before Sunset Edge lost its residents. Plot B is where the film’s subtext–about the uniquely teenaged inability to understand death and the violent, confrontational nature of life–is most comprehensible. “Sunset Edge” has a secret at its heart, but it’s only interesting in terms of the thematic ripples it creates in the film’s eerily still narrative waters.

Unfortunately, those ripples aren’t strong enough to sufficiently shake up Plot A. Malachi’s story is only relatively compelling: when he interacts with his family during flashbacks, he doesn’t move around like a lost wind-up toy the way that Haley and her friends do. Still, if you look at Plot B as a discreet narrative, you’ll find that Malachi’s sub-plot is nothing but eliptically edited flashbacks, vague dialogue, fussily mannered cinematography, and a big revelation that’s actually kind of predictable. Malachi is, in other words, not that different from Haley and her companions. he walks around as if on egg-shells, and watches as his family behaves without compelling or discernible logic. They act like ghosts, and he tries to make himself scarce.

Knowing that Malachi’s mood is a reflection of the tense atmosphere that surrounds Sunset Edge doesn’t necessarily make the existential experience of watching “Sunset Edge” that much more compelling. In fact, if I were to tell you what it’s like to watch “Sunset Edge,” I’d tell you it’s a lot of shots of tree branches swaying in the breeze, and freakishly quiet kids wandering through empty homes. Characters don’t think in this film, they just absorb information so they can think about what they’re looking at after the film is over. That may be true to life, but it’s not exactly dramatic dynamite. More often than not, “Sunset Edge” feels like a drawn-out first act for what might have been a decent movie.