“Sugar Town” knows its characters. It inhabits two overlapping worlds in Los Angeles: the world of people who were famous once, and those who will never be famous but dream of nothing else. “We were all in seminal bands in the ’70s and ’80s,” a middle-age rock musician observes, sadly and defiantly, at a meeting to discuss forming a new band. The problem with being seminal is that you end up in the shadow of your offspring.

These has-beens have money. Not a lot, in some cases, but enough. The movie slides easily in and out of their homes, comfortable, untidy structures in the Hollywood hills, strong on the “features” real estate agents brag about, but looking knocked together out of spare parts of better houses. Their clothes and hair reflect the way they looked when they were famous; their images are made from last year’s merchandise.

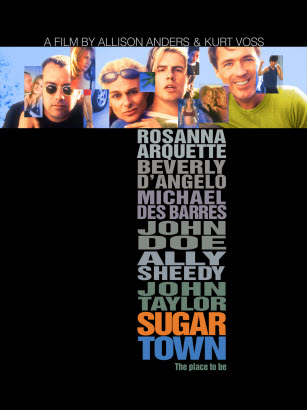

The movie’s insider atmosphere is honestly come by. The co-directors, Allison Anders and Kurt Voss, live in this world themselves, many of the actors are their friends, the houses are where some of these people actually live, and the movie was shot in three weeks. If it were a documentary, it would be a good one.

The problem with being 40ish is that you’re still young enough to want to do dangerous things, but too old to ignore the dangers. Drugs are not free from the shadow of rehab. Sex is a need but not a drive; you want it, but it’s so much trouble to go out and get it. Always at your back you hear time’s winged chariot drawing near. It’s bad enough to be asked to play Christina Ricci’s mother, as a former slasher movie queen (Rosanna Arquette) observes, but worse because “she’s not an ingenue anymore.” The movie cuts between a rich assortment of characters; it’s like a low-rent, on-the-fly version of Robert Altman’s “The Player” or “Short Cuts.” We meet a production designer (Ally Sheedy) who is so paralyzed by self-help mantras that she has no social life. “Your genital area is completely blocked,” says her “openness counselor,” offering a massage which we suspect could unblock it using the most traditional of approaches. Her house is a mess. She hires a housekeeper (Jade Gordon), a showbiz wannabe we see badgering a drugged-out composer for the “three hit songs” she has paid him to write. When Sheedy finally gets a date (with a music agent), the housekeeper sabotages the date by advising against a sexy black dress and in favor of a painting smock that’s “more you,” then gets a ride home from the agent and descends directly to openness counseling.

Arquette’s former slasher queen lives with an ’80s rock hero (John Taylor of Duran Duran). One of his former lovers dumps a kid at his door–his kid, she says–and disappears. The kid (Vincent Berry) hates his name, which is Nirvana. He’s about 11, wears earrings and black eye makeup, and is very angry. “I SAID–call me NERVE!” he snaps at her. “You want some hot chocolate?” she asks. He softens up considerably when he realizes she is the star of his favorite slasher videos.

Other characters include the pregnant wife (Lucinda Jenney) of a studio musician, her drug-damaged brother-in-law and the Latino musician who wants to seduce her husband. Jenney’s performance is the most touching in the movie, especially in the way she handles the brother-in-law. The rock agent, named Burt (Larry Klein), strikes gold. He discovers a rich widow (Beverly D'Angelo) who will provide backing for an album if she can sleep with a former glam-rock star (Michael Des Barres). Their scene together is the movie’s funniest; he painstakingly reproduces his famous image with makeup and clothes, only to have her size up his bare-chested leopard leotard and ask, “Did you pull this out of mothballs just for me?” One thing you notice in Los Angeles is that everyone seems to be connected to “the business” in one way or another, if only in their plans. Sheedy meets a wheatgrass machine operator at the health food store, who turns out of course to have a screenplay and newly taken publicity stills. There’s a certain double-reverse poignancy in observing that some of the cast members (Michael Des Barres, John Taylor, Martin Kemp) are indeed rock legends, and others, such as Ally Sheedy, are in the midst of actual career comebacks like the others dream of.

The movie is not profound or tightly plotted or a “statement,” nor should it be. It captures day-to-day drifting in a city without seasons, where most business meetings are so circular and unfocused it’s hard to notice when they stop resulting in deals and simply exist for their own sake. You can make enough money in a brief season of fame that if you are halfway prudent with it, you can live forever like this, making plans and reminding people who you are, or were, or will be.