Gene Siskel proposed an acid test for a movie: Is this film as good as a documentary of the same people having lunch? At last, with “Stolen Summer,” we get a chance to decide for ourselves. The making of the film has been documented in the HBO series “Project Greenlight,” where we saw the actors and filmmakers having lunch, contract disputes, story conferences, personal vendettas, location emergencies and even glimpses of hope.

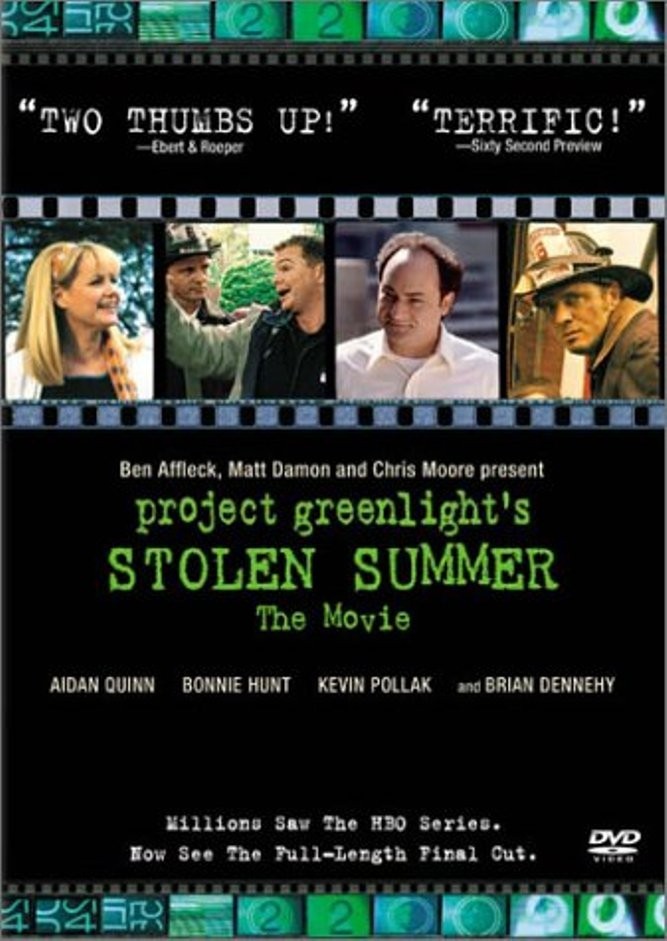

Movies are collisions between egos and compromises. With some there are no survivors. “Stolen Summer” is a delightful surprise because despite all the backstage drama, this is a movie that tells stories that work–is charming, is moving, is funny and looks professional. That last point is crucial, because as everyone knows, director Pete Jones and his screenplay were chosen in a contest sponsored by Miramax and actors Ben Affleck and Matt Damon. Miramax gave them a break with their screenplay “Good Will Hunting,” and they wanted to return the favor.

“Stolen Summer” takes place on the North Side of Chicago in the summer of 1976, when an earnest second-grader named Pete O’Malley (Adi Stein) listens in Catholic school and believes every word about working his way into heaven. Seeking advice from a slightly older brother about how to guarantee his passage to paradise, Pete is startled to learn that the Jews are not seeking to be saved through Jesus. So Pete sets up a free lemonade stand in front of the local synagogue, hoping to convert some Jews and pay for his passage.

There is already a link between Pete’s family and that of Rabbi Jacobson (Kevin Pollak). Pete’s dad, Joe (Aidan Quinn), is a fireman who dashed into a burning home and rescued the Jacobson’s young son Danny (Mike Weinberg), who is about Pete’s age. Pete has already met the rabbi and now becomes best friends with his son, although Danny is not much interested in the theology involved, he joins Pete’s “quest” to get them both into the Roman Catholic version of heaven. Is Pete’s obsession with church rules and heaven plausible for a second-grader? Having been there, done that, I can state that this was not an unknown stage for Catholic school kids to go through, and that I personally knelt in prayer on behalf of my Protestant playmates, which they found enormously entertaining.

The touchier question of “converting the Jews” is handled by the movie so tactfully that it is impossible not to be charmed. The key performance here is by Pollak, as a rabbi whose counterpoint to Pete’s quest involves understated reaction shots and instinctive sympathy and humor. When the Jacobsons invite Pete over for lunch, he makes the sign of the cross and when the rabbi asks why he’s doing it (the unstated words are “at our table”), Pete explains solemnly, “It’s like picking up the phone and being sure God is there.” Earlier, during his first visit inside the synagogue, Pete is surprised to find no crucifix hanging from the ceiling, and confides to the rabbi: “Sometimes I think of climbing up and loosening the screws and letting him go.” The movie cuts between Pete’s quest, which is admittedly a little cutesy, and the completely convincing marriage of his parents, Joe and Margaret (Bonnie Hunt). These are (I know) actors who grew up in Chicago neighborhoods and were raised (I believe) as Catholics, and they are pitch-perfect. Note the scene where Hunt is driving most of her eight kids to mass and the troublesome Seamus is making too much noise in the back seat. Still driving, she reaches out to him and beckons him closer, saying, “Come closer…come on, come on, I won’t hit you,” and then smacks him up alongside the head. Every once in a while a movie gives you a moment of absolute truth.

Danny has leukemia, which he explains solemnly to Pete, who is fascinated. Danny’s mother is worried about her young son spending so much time with Pete, but the rabbi observes it may be Danny’s last chance to act like a normal kid. The “quest” involves such tests as swimming out to a buoy in Lake Michigan, and while we doubt that, even in innocent 1976, second-graders were going to the beach by themselves, we understand the dramatic purpose.

The most fraught scenes in the movie involve the synagogue’s decision to thank the O’Malley family after Joe risked his life to save Danny. They settle on a scholarship for Patrick, the oldest O’Malley boy, and the rabbi is startled when Joe turns it down in anger. Joe tells his wife: “It’s about the Jews helping out some poor Roman Catholic family so they can go on TV and get free publicity.” Is this anti-Semitism? No, I think it’s tribalism, and Joe O’Malley would say the same thing about the Episcopalians, the Buddhists or the Rotary Club. Bonnie Hunt’s response is magnificent: If Joe doesn’t let his son accept the scholarship, “So help me God, when you come home at night, the only thing colder than your dinner will be your bed.” “Stolen Summer” is a film combining broad sentiment with sharp observation, although usually not in the same scenes. I don’t know if writer-director Jones came from a large Irish-American family on the North Side, but do I even need to ask? The movie even has Brian Dennehy, patron saint of the Chicago stage, as the parish priest. In a time when so many big-budget mainstream movies are witless and heartless, “Stolen Summer” proves that studios might do just about as well by holding a screenplay contest and filming the winner.