Beneath the weathered baseball cap and bushy goatee, the parade of plaid shirts and the polite replies of “Yes, ma’am,” there’s a whole lot more to Bill Baker. Sure, he listens to old-school country in his pickup truck while driving between manual labor gigs and he never fails to pray before a meal, even if it’s tater tots and a cherry limeade from Sonic. It seems perfectly natural to him to keep a couple of guns in his run-down Oklahoma home, and he never misses an opportunity to watch his favorite college football team.

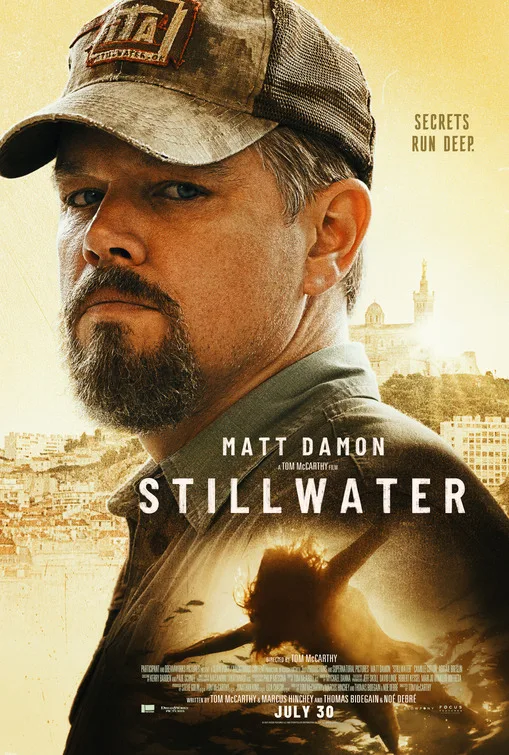

But there’s something simmering within this collection of red-state stereotypes, and “Stillwater” is at its best when it explores those complexities and contradictions. Beefed-up and sad-eyed, Matt Damon brings great subtlety and pathos to the role, especially when he cracks his stoic character open ever so gently and allows warmth, vulnerability, and even hope to shine through on his road to redemption. But Bill’s tale of hard-earned second chances is one of many stories director Tom McCarthy is telling in “Stillwater,” and while it’s the most compelling, it also gets swallowed up almost entirely during the film’s insane third act.

The script, which McCarthy co-wrote with Thomas Bidegain, Marcus Hinchey, and Noe Debre, loosely takes its inspiration from the case of Amanda Knox, the American college student convicted in 2007 of killing her roommate while studying abroad in Italy. Eight years later, Knox was acquitted. “Stillwater” moves the action to the French port city of Marseilles and introduces us to Bill’s daughter, Allison (Abigail Breslin), after she’s already served five years of a nine-year prison sentence for the murder of her lover, a young Muslim woman.

Allison insists she’s innocent; Bill resolutely believes her. And so “Stillwater” is also the story of a father and daughter trying to mend their strained relationship as he makes frequent visits to chat and do her laundry and she pretends to care as he prattles on about Oklahoma State football. (The college campus is in—that’s right—Stillwater, Bill and Allison’s hometown. But as you’ve probably guessed by now, the title refers to our hero’s demeanor, as well.) “Life is brutal,” each of them says at one point, and one of the more intriguing elements of “Stillwater” is the notion that being a screw-up is hereditary, which pushes against its feel-good, Hollywood-ending urges.

But wait, there’s more—so much more. Because the primary driving narrative here is the possibility that Allison can prove her innocence based on jailhouse hearsay about an elusive, young Arab man. Here, “Stillwater” becomes a procedural reminiscent of McCarthy’s Oscar best-picture winner “Spotlight,” as Bill knocks on doors and follows one lead after another, talking to people who either help him or don’t in his efforts to exonerate his only child. In this vein, it’s also about the racial tensions and socioeconomic disparities that exist in both France and the United States, and the blindly confident swagger with which some Americans carry themselves overseas—even someone like Bill who is, to borrow from the Tim McGraw song, humble and kind.

And for a big chunk of its midsection, it’s about a middle-aged man forming an unexpected friendship—and then a makeshift family—with a single mom and her little girl. Virginie (a vibrant and charismatic Camille Cottin) and her daughter, Maya (an adorable and steely Lilou Siauvaud), give the widowed Bill a shot at righting the wrongs of his past. Virginie and Bill initially connect when she offers to help him in his investigation by making calls, translating and generally serving as his guide through an ancient city he’s barely gotten to know. The relationship makes zero sense on paper—she’s a bohemian actress, he’s an oil-rig worker—but the small kindnesses they show each other allow them to forge a bond, and allow Bill to reveal more about himself and his tortured history, piece by piece. It sounds cheesy, but surprisingly, it works.

This is far and away the strongest section of “Stillwater,” and if the majority of this film had focused on this understated dynamic and the quiet hope of better days to come, it would have been more than satisfying. The performances here are lovely, and Damon enjoys distinctly sweet connections with both Cottin and Siauvaud. But then it takes a significant turn into darker territory toward the end, with twists predicated on major coincidences and reckless decisions. “Stillwater” also becomes a far less interesting film as it slogs through its overlong running time. While it’s fascinating to consider Bill’s self-destructive streak rearing its head once again, even after it seems he’s finally found some peace, the way it plays out is so wild and implausible, it feels like it was ripped from an entirely different movie and grafted on here. Within this eventful stretch, there’s also a suicide attempt that’s tossed in almost as a baffling afterthought, as it’s never mentioned again.

Ultimately, the cacophony of all these plot lines converging and the weight of the messaging being conveyed is almost too much to bear. Details get spelled out and characters explain their motivations when maintaining an overall air of mystery would have been far more effective. Whether or not Allison is guilty isn’t the point; enjoying a moment of stillness and solitude in the afternoon sunshine is, even if it’s fleeting.

Now playing in theaters.