Perhaps one of the most unfortunate but inevitable reactions to Alex Gibney’s “Steve Jobs: The Man in the Machine” would be that it’s a “takedown” of the Apple co-founder. It’s not. Surely, the film subjects Jobs’ cult of personality to such severe scrutiny that it goes a long way toward dismantling it. But that’s part of a complex portrait that gives as much weight to Jobs’ world-changing talents as to his personal flaws.

In contrast to most of Gibney’s documentaries, which are told in a standard third-person style, usually without narration, this one has a more personal tone from the outset, as a way of recognizing and probing the reality that, more than any other figure, Jobs put the “personal” in personal computer and the many, increasingly intimate devices descended from it. As one interviewee puts it, he created machines that “felt like an extension of the self.”

Charting his own relationship to Jobs and his creations via occasional voice-over, Gibney starts off by confessing his own mystification at the worldwide outpouring of grief that greeted Jobs’ death of cancer in October 2011. He had seen such emotional reaction to the untimely demises of Martin Luther King, Jr. and John Lennon, the filmmaker says, but Jobs was not a heroic civil rights activist or a great artist. What was the meaning that he held for so many people, and was that adulation justified or misplaced?

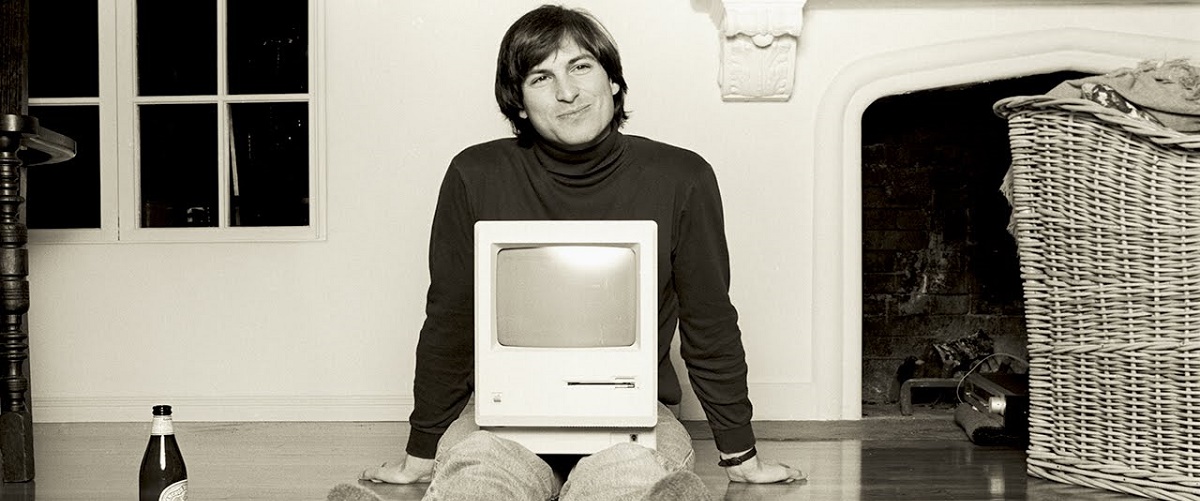

This premise serves as a springboard for a chronicle of Jobs’ life and career that proceeds in more of a thematic than a chronological fashion, and that includes plenty of material from interviews that Jobs gave over the years. By the subject’s own account, he got interested in computers as a teenager and, by virtue of living in northern California, gained access to companies like Hewlett-Packard and Atari, where he was able to meet like-minded young people and deepen his fascination with professional experience.

But even here, there were signs that behind his energetic, idealistic exterior, Jobs the man could be “ruthless, deceitful and cruel,” to use Gibney’s words. In one telling incident, Jobs shafted his future Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak by not telling him of a bonus they had earned on a project. The amount wasn’t large and “Woz” says he would have gladly given it all to Jobs; what hurt was being cheated by his supposed friend.

After charting the founding of Apple, which shrewdly positioned itself as the David to IBM’s Goliath and embodied all of Jobs’ visionary sense of the computer’s potential for changing individual lives (especially with the triumphant introduction of the Macintosh in 1984), the film doubles back to examine his early years as the product of the counter-culture of northern California in the 1960s and ‘70s, a seeker who went off to India looking for (but not finding) a guru and later embracing Zen Buddhism, which had a significant impact on his minimalist aesthetic sense.

Too bad the aesthetic purpose didn’t entail a personal-ethics component. The long-haired, unwashed, Bob Dylan-worshipping early Jobs may have looked like a groovy guy, but he behaved like a privileged ass. After lengthy denials that he fathered a child by girlfriend Chrisann Brennan were disproved by DNA tests, he begrudged having to pay $500 a month in child support when he was worth $200 million.

Gibney made his film without the cooperation of Jobs’ wife and their children or Apple, and thus his account doesn’t have either the authorized angle or wealth of insider-ish detail of Walter Isaacson’s capacious biography, which, among other differences, puts a greater emphasis on Jobs’ feelings as an adopted child. But the film and the book don’t reach dissimilar conclusions, and Gibney’s account has the cinematic virtue of including some very emotional interview material that couldn’t be equaled by the printed page. (We’ll soon be able to see how the written and documentary-film versions compare to the dramatized take offered in the Danny Boyle’s upcoming biopic, starring Michael Fassbender as Jobs.)

Naturally, Jobs’ life contained more than one act, and if Gibney gives relatively short shrift to the second, in which Jobs, forced out of Apple in 1985, co-founded NeXT and helped revolutionize computer animation in backing Pixar, the filmmaker aptly puts the emphasis on the third, when Jobs returns to the near-bankrupt Apple in 1997 and commences the era that will be bring the world the iPhone, iPod and iPod and transform the company into the world’s wealthiest.

It was in this era that Jobs sealed his place as the face of Apple as he made a habit of dazzling the press with dramatic announcements of new products that had often had the dazzling force of a new Beatles album’s unveiling. More than one interviewee comments that Jobs’ real genius was as a storyteller, one whose skills at shaping narratives (including foreseeing the next developments beyond the current one) included crafting a persona for himself as a beneficent technological wizard.

There was obviously some truth to that, but it also contained a large measure of the facile wish-fulfillment and eyewash common to all effective advertising. And behind the wizard’s screen, there was much that looks highly unflattering in Gibney’s telling, including Apple’s exploitation of low-paid Chinese workers, the off-shoring of company assets to avoid U.S. taxes, and the backdating of stock transactions, a sleazy episode in which one of Jobs’ most valuable lieutenants was thrown under the bus to save him.

Ultimately, Gibney is right to return the film’s focus to himself and the viewer, for we–all of us iPhone users and lovers–are the real source of Jobs’ and Apple’s power and fascination. If the film finally comes off as somewhat less accomplished than his “Enron,” “Taxi to the Dark Side” or the recent and somewhat similar “Going Clear,” that’s perhaps because it’s easier to draw a bead on the bad guys at the center of those films than on complex, elusive and strangely paradoxical characters like Steve Jobs–or ourselves.