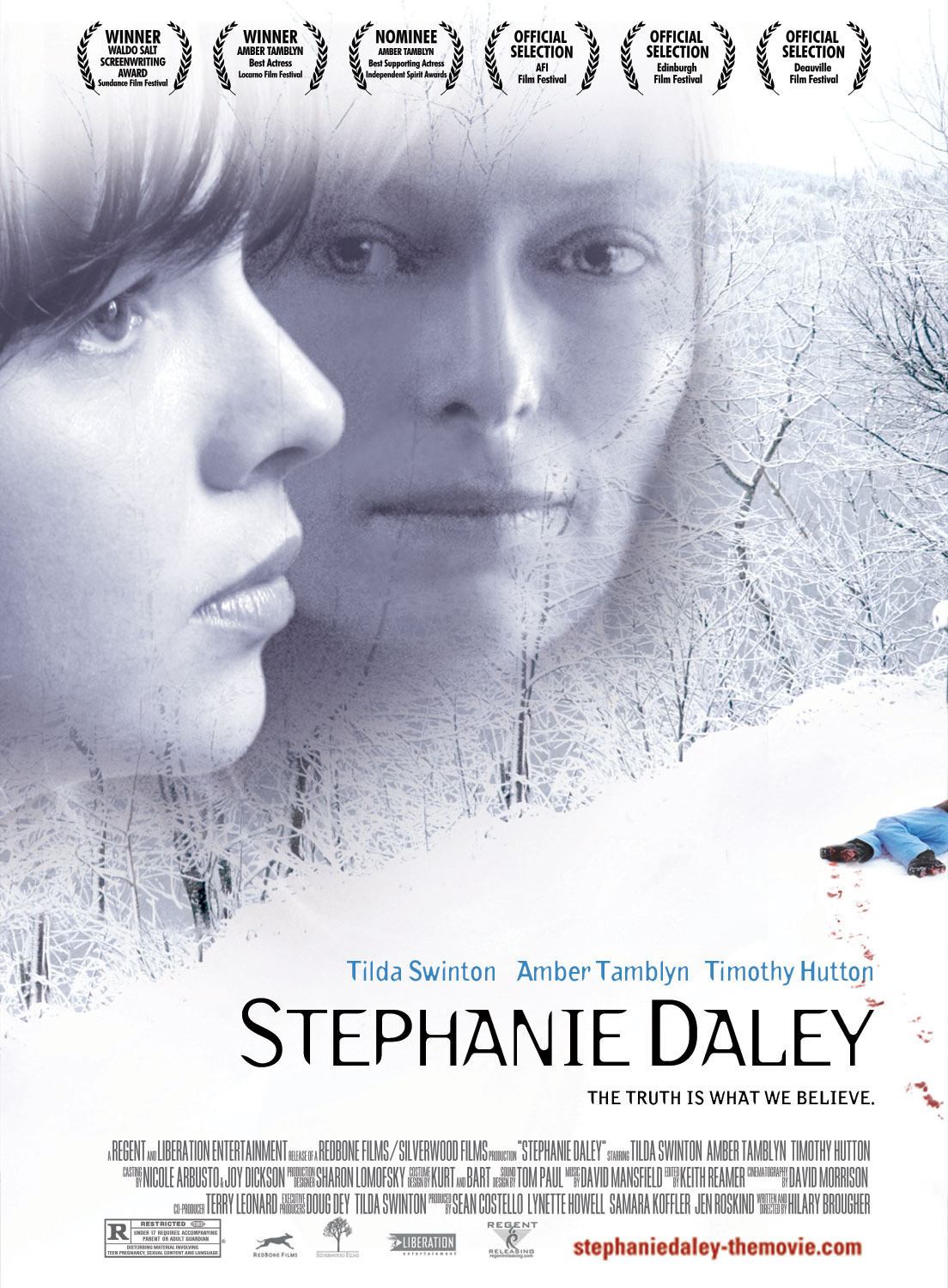

At a high school ski outing, a trail of blood is visible in the snow. The trail is left by Stephanie Daley, a 16-year-old girl, whose stillborn baby is found in a toilet. The girl claims that she didn’t know she was pregnant, but the “ski mom” case becomes a sensation. She is charged with murder, and before her trial, is sent for sessions with a forensic psychologist named Lydie Crane.

Stephanie (Amber Tamblyn) has an imperfect understanding of the realities of pregnancy. She had sex only once, at a party, with a young man who told her not to worry; he withdrew in time. Obviously, he did not. Why didn’t she realize she was pregnant? It can happen. But confusing evidence suggests the baby may not have been dead at birth, although it was barely long-term enough to live. Did she kill it, or was it already dead?

The psychologist, Lydie Crane (Tilda Swinton), had a miscarriage of her own. Now she is expecting again — about as pregnant as Stephanie was. Their conversations are almost in code, with much silence. The girl is inarticulate, guilt-ridden (“I killed her with my mind”) and confused. The psychologist deals with her personal conflicts over the case. Swinton is an ideal choice for the role, because when she needs to, few actors can be more quiet, empathetically tactful.

There are courtroom scenes, but this is neither a whodunit, a what-was-done or a moral or political argument from any position. It simply, sympathetically, sees how real life can be too complicated to match with theories.

I personally believe the body of a stillborn infant deserves respect. It should not be found in a toilet. But we learn that the psychologist herself threw away the ashes of her own stillbirth. Heartless? Depends on the thinking at the time. Scattering someone’s ashes can be a loving and spiritual act. A libertarian, on the other hand, might reasonably argue that while a living baby has full human rights, a stillborn baby does not, and remains, in a sense, the property of the mother. In this film, that argument grows cloudy because it is unclear when and how the baby died.

We read about cases like this and think the mothers are monsters. If their babies are alive and found in a trash bin, certainly they exist outside decency and morality, or their values are corrupted.

But what led them to that decision? What did they know? What were they taught? What did they fear? I feel it is the responsibility of parents to raise children who know they can tell their parents anything, and go to them for help. If a girl cannot tell her parents she is pregnant, something bad is likely to happen.

Yet “Stephanie Daley” goes even deeper: Did she know she was pregnant? As the psychologist struggles with this baffling girl, she feels her own powerlessness. And the movie invites us into her pity and confusion. Written and directed by Hilary Brougher, it has the courage and integrity to refuse an easy conclusion. When I saw it, some audience members said they were unhappy with the ending. What they meant was, they were unhappy about having to think about the ending.

What would a satisfactory ending be? Guilty? Innocent? Forensic revelations? We have been tutored by Hollywood to expect all the threads to be tied neatly at the end. But real life is more like this movie: Frightened and confused people are confronted with a situation they cannot understand, and those who would help them are powerless. Some cases should never come to trial, because no verdict would be adequate. You are likely to be discussing this film long into the night.