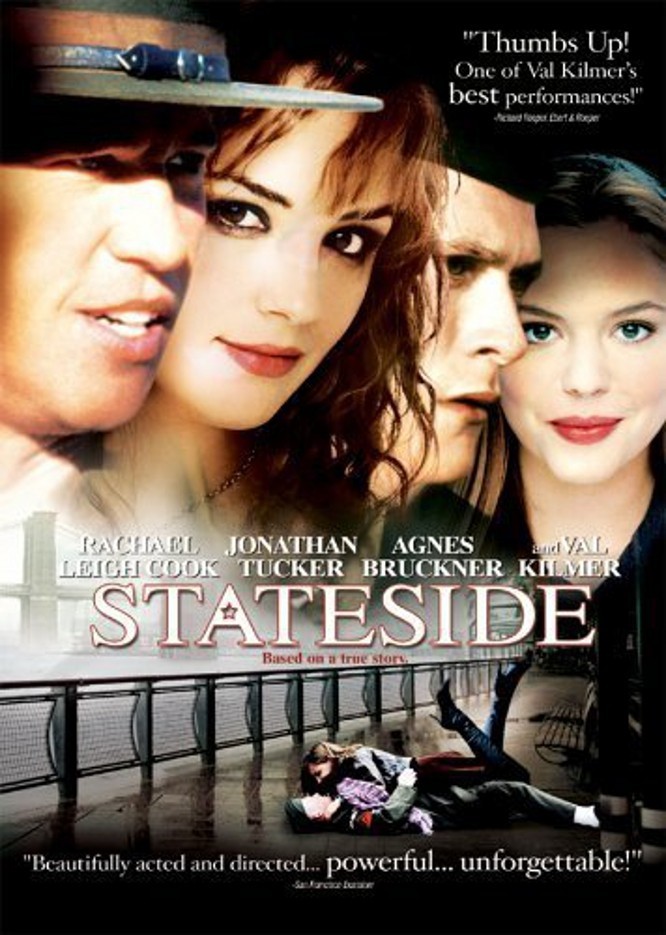

‘Stateside” tells the story of a rich kid who joins the Marines to stay out of jail, and then finds himself in love with a famous actress and rock singer who is being treated for schizophrenia. Stated as plainly as that, the plot could have been imported from a soap opera, but the writer-director, Reverge Anselmo, assures us it is “based on a true story.” Perhaps. Certainly he rotates it away from sensationalism, making it the story of an irresponsible kid who is transformed by boot camp and then becomes obsessed with what he sees as his duty to the actress.

The kid is named Mark (Jonathan Tucker). He goes to an upscale Catholic high school, drinks too much one night, and is driving a car that broadsides the car of their headmaster, Father Concoff (Ed Begley Jr). The priest is paralyzed from the waist down, but doesn’t sue (he explains why, but so enigmatically it doesn’t work). Mark’s millionaire father (Joe Mantegna) pulls strings to have the charges dropped in exchange for Mark enlisting in the Marines.

Mark goes to Parris Island for basic training, under the command of a drill instructor named Skeer (Val Kilmer). Skeer doesn’t like the rich kid and makes it hard on him; the kid puts his head down and charges through, emerging at the end of the ordeal as what Skeer, if not all of the rest of us, would consider a success.

Home on leave before more training, he visits his girlfriend. That would be Sue (Agnes Bruckner), who lost her front teeth in the crash but lost her freedom after her mother (Carrie Fisher) found some sexually explicit letters she wrote. The letters are obviously evidence of madness, so she’s institutionalized, in the Connecticut version of “The Magdalene Sisters.” When Mark visits her, he meets her roommate Dori (Rachael Leigh Cook), and they fall in love.

All of this sounds simpler than the movie makes it. The opening scenes are disjointed and confusing, and it doesn’t help that the characters sometimes seem to be speaking in poetic code. We meet Dori early in the film, before Mark does, when she has a breakdown onstage and walks away from her band. But the movie doesn’t make it clear who she is or what has happened, and we piece it together only later.

Famous as she is, she is also troubled, and Mark’s steadfast loyalty and level gaze win her heart. She wouldn’t ordinarily date a man from boot camp, even a rich one, but Mark’s letters tell her he will stand by her, and she believes him. So do we, after he manages to balance the Marines with trips home, springing her at various times from mental institutions and hospitals. These moments of freedom are heady for her, and she enjoys getting out from under her medication, too. But her therapist (Diane Venora) solemnly explains to Mark that he is bad for Dori, that she needs her medication, that she can be a danger to herself. One conversation between them is especially well handled.

The point of the movie, I think, is that the Marines make Mark into a man, but he takes his newfound self-confidence and discipline and uses it to commit to a lost cause. He doggedly persists in his devotion to Dori because he loves her, yes, but also because her helplessness makes him feel needed, and her illness is a test of his resolve.

Perhaps the movie is based on more of the true story than was absolutely necessary. Toward the end of the film, Mark is part of the Marine landing in Lebanon and then returns home gravely wounded. This happens too late in the film for the consequences to be explored, especially in terms of his relationship with Dori. “Stateside” might have been wiser to bring the Mark-Dori story to some kind of a bittersweet conclusion without opening a new chapter that it does not ever really close.

The performances are strong, although undermined a little by Anselmo’s peculiar style of dialogue, which sometimes sounds more like experimental poetry or song lyrics than like speech. It is also hard to know how to read Dori; we believe the therapist who says she is very ill, but her illness is one of those movie conveniences in which she is somehow usually able to do or say what the screenplay requires. There’s also the enigma of Mark’s father, played by Mantegna as a remote, angry man who carts an oxygen bottle around with him. We sense there’s more Anselmo wants to say about the character than he has time for. “Stateside” plays like urgent ideas for a movie which Anselmo needed to make, but they’re still in note form.