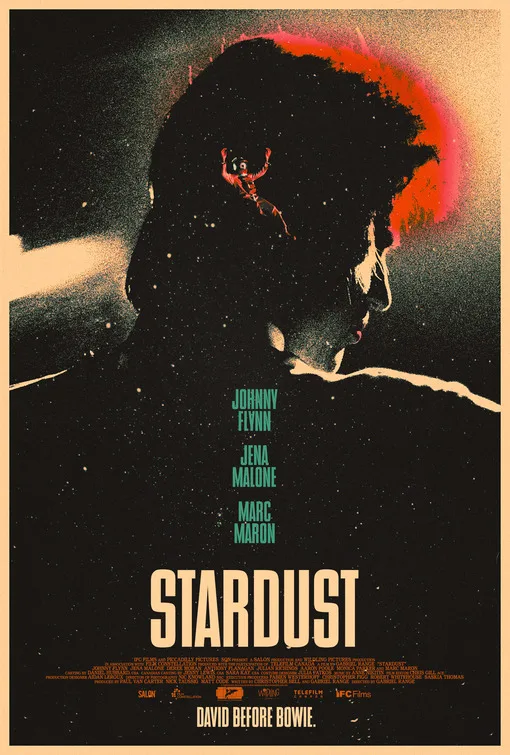

David Bowie played many personas in his lifetime. A space alien, a dapper fashion icon, an astronaut, a goblin king, whatever cocaine fever dream The Thin White Duke was supposed to be. What Bowie never played was boring, and I’m sorry to say that for the most part, that’s what you’ll find in Gabriel Range’s fan fictionalized portrait of the British singer’s first trip to America.

In “Stardust,” we find David Bowie (Johnny Flynn) on the rise but frustrated. He’s broken out with “Space Oddity,” but now what? He’s too niche to be considered mainstream, but still he wants to achieve that rock star status. So, he crosses the pond to meet an enthusiastic publicist, Ron Oberman (Marc Maron), for a tour. Only when Bowie arrives, he learns he can’t actually play in the States, not legally anyway. So, he’s booked a series of private concerts, at which Oberman will try to talk him up to the right people. Along the way, Oberman tries to navigate their way through the thornier sides of the music industry and America.

Christopher Bell and Gabriel Range’s story had potential. After all, “Stardust” is set in 1971, a crucial moment in Bowie’s career. The trip to the U.S. helped inspire the creation of his Ziggy Stardust persona, one of the earliest reinventions for young David Jones that launched his career into the stratosphere. Bowie could have been a one-hit wonder, a curio who gave us “Space Oddity” and faded back into obscurity. Yet what makes it to the screen is just that—the concept. The narrative loses steam as it rolls on, its signs of life fading with every rock star biopic cliche that shows up, from the “people just don’t understand” musings to the distressed marriage.

Perhaps the worst of these is the way the movie weaves in Bowie’s half-brother Terry Burns (Derek Moran) as the specter of mental illness, something to torture the film’s sensitive genius and remind him that he could lose his mind just the same. The movie posits that Terry’s therapeutic treatment inspired Bowie to perform as other personas, but by that point in his life, the musician had already studied theater and mime, which the film even makes into a running gag. The audience is supposed to believe that a false cathartic moment with his brother led to the idea of playing different characters on stage? Not likely, but then again, this fictionalized account of Bowie goes west offers little basis in reality.

What is true is that Bowie really did crash land at the Oberman’s family home in Silver Springs, Maryland, in 1971. “David Bowie, this is my mother,” Oberman says as he picks the artist up at the airport, leading him not to the nice black car but the green family vehicle parked in front of it. It’s one of a handful of funny moments Maron and Flynn manage in their buddy road trip movie that plays a bit like “Driving Mr. Bowie.” There’s a power differential between the two men, artist and publicist, someone whose career is on the rise and the other who is losing his standing, those who have potential and the people around them who try to get others to see what they see. But the movie never really digs into that.

Instead, Flynn channels the shadow of a ghost of Bowie. His portrayal is that of a passive wallflower, not a man who knew when to stay silent to keep an air of mystery. His wife Angie (Jena Malone), Oberman, and managers argue over him, but he retreats and pouts that he just wants to be a star. It’s like a shallow facsimile of the artist. This might be personal projecting, but one doesn’t usually study pantomime to become a rock god. Bowie became a headliner to make the weirdo art he wanted to make. The movie understands that differently.

Maron, for his part, makes the most out of this nothing burger, occasionally injecting some life into a limp story and excellently delivering deadpanned lines, even if they’re of dad-joke quality. His presence props up Flynn’s uncharismatic performance, giving a moment like Bowie’s less-than-stellar pitstop to see Andy Warhol at The Factory some heart. As Oberman, Maron switches gears from feeling dejected over getting left out in the cold to trash talking Warhol to make Bowie feel better that the famous artist wouldn’t talk to him. The “never meet your heroes” sequence then becomes a genuine discussion about pop art. Maron’s eagerness, sometimes desperation, as Oberman to convince journalists and radio hosts to “give the kid a chance” is the most convincing performance in the movie.

However, Angie Bowie is given a much less charitable treatment. She may be a controversial figure in her husband’s story, but “Stardust” really only provides her space to act like a terror, one more power hungry than any of the musicians in the room. She might be the stage wife to outdo all stage wives, at one point barking into the phone at Bowie, “You can’t come home until you make it.” Poor Malone practically spends all of her time on-screen yelling, scowling, or exerting her control. Angie’s made to be quite the definition of a one-note character, one that smacks of sexist tropes.

The lack of a solid narrative means “Stardust” cannot compensate for the production’s modest budget, which lacks a noticeable amount of Bowie songs and includes many scenes filmed on the cheap. A crowd scene of outreached hands is made up of maybe 25 people, numerous driving scenes look like they were filmed in a studio, and so on. This is neither “Bohemian Rhapsody” or “Rocketman” levels of recreated concerts and dramatized inner demons. This is a rough draft that seems to be missing quite a few elements to make a good idea into a great movie.