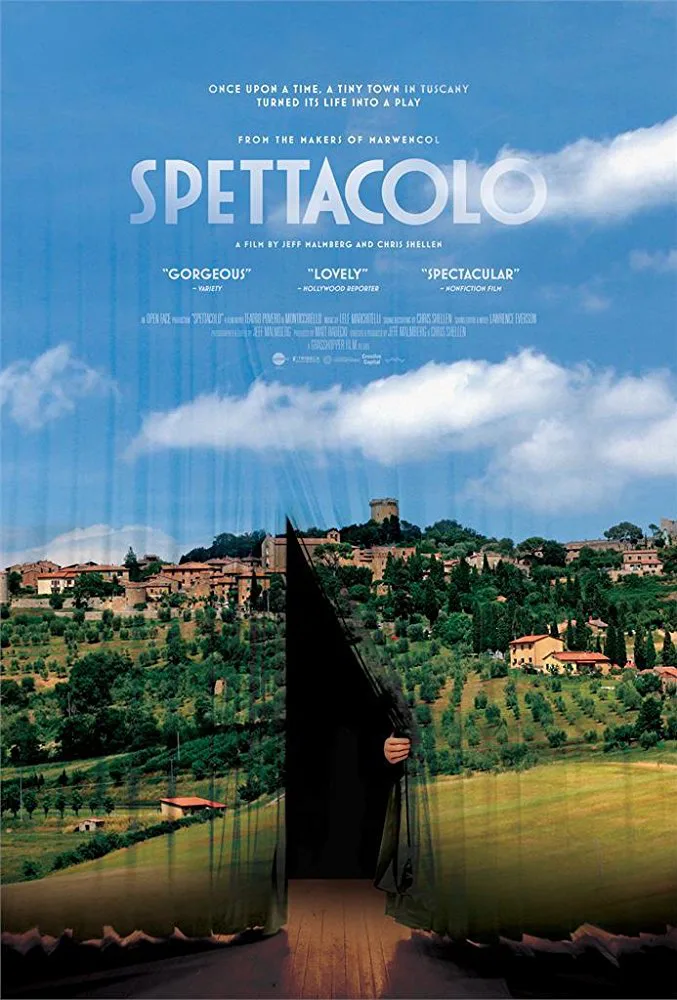

Tucked away in the hills of Tuscany, the small village of Monticchello puts on an original play every year, starring its residents, working from material inspired by their current anxieties and passions. They’ve been doing this for 50 years, but no one has offered an in-depth look until filmmakers Jeff Malmberg and Chris Shellen (“Marwencol”). As their production is documented rehearsal by rehearsal, “Spettacolo” is not a type of Charlie Kaufman-esque enterprise like a real-life “Synecdoche, NY,” but it is a touching document of seemingly regular people who yearn to keep an artistic tradition alive.

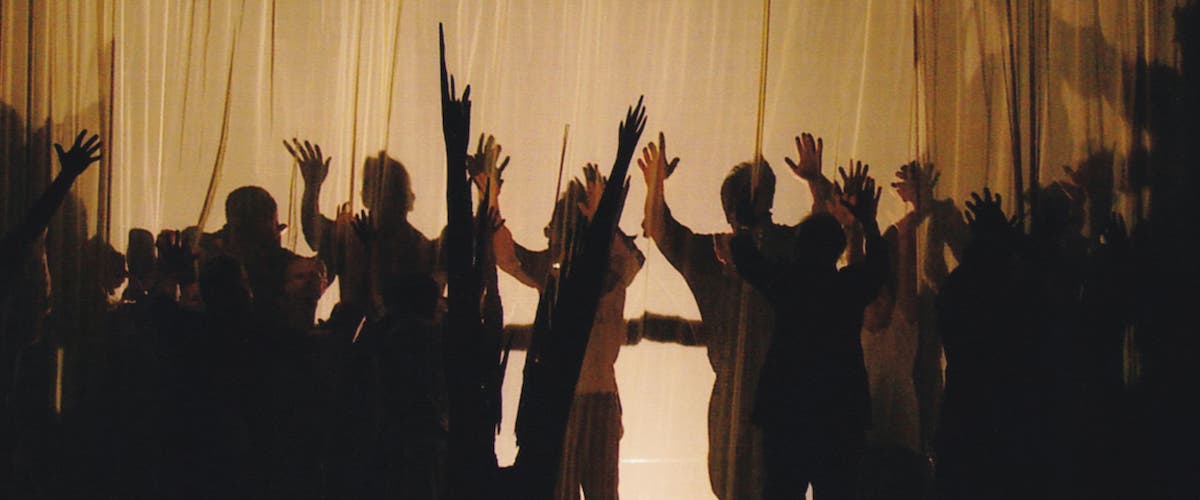

The history of the Teatro Povero di Monticchello is presented through an impressive amount of archival material. Photo negatives, footage and modern interviews loop us into the history of this town theater, which is indeed fascinating. It all started, in part, when the town famously protected partisan soldiers against fascists, and were almost executed until an officer let them go. Years later, they would start putting on theatrical productions that were period pieces, but then opted for modern, meta pieces, or “autodramas,” where their current mindsets would be out on stage. They had reoccurring actors, like Alpo, Edna, and Arturo; a curious man with flowing hair named Andrea would go from becoming an actor to the director and writer, approaching each play with the seriousness of Broadway. You can tell from the contents of this archival material—the various sets, the strange costumes, the raucous scenes—how the theater became a town-wide pride and expression.

When Malmberg and Stellen arrive to make this film, however, the place is much different. A third of the cast members are dead and the next generation do not seem all that interested in the production. And yet there is a spirit to keep going, especially as they hook onto a scenario that speaks to their current anxieties: economic dominance as Monticchello becomes filled with tourism, killing the way of life they have known. The play they settle on concerns the end of the world, with greedy banks buying up the land.

A main problem, or prominent factor for this albeit well-made documentary, is timing. This detailed idea of what was also creates a nagging idea of what this could have been if someone were to have made a film about all of it decades ago. No points are taken away for that instilled curiosity, but it certainly changes how the documentary functions and plays out, especially with the theater’s best production happening years ago. “Spettacolo” is about the past, the wilting present and questionable future of this long tradition, and is best approached as an elegy to a tradition we are just starting to appreciate.

Malmberg and Shellen learned Italian for the project and moved to Monticchello, which explains in large part how this story feels so intimate. As it observes people quietly and shares the history of the play, it feels like a project made from the inside but for a public audience, much like the theatrical productions themselves. When tourists are presented in the film, with their loud rolling luggage tearing through the peaceful landscape of Monticchello, their presence in turn feels entirely alien, unwelcome. Using the simple beauty of their setting their amicable subjects, Malmberg and Shellen make a great case for how tourism will truly be the end of the world.

The embedded nature of the film informs the often breathless beauty in its cinematography, which is often shown for a few seconds in montages accompanied by string quartet classical music. The sights are plain but quite effective: two men talking on a bench about how one-third of the original actors have died, a woman doing her laundry on a fence while a gorgeous set of hills sits in the background without a single tourist bus on it. “Spettacolo” does more than put a spotlight to this incredible tradition, it captures a way of life for a very non-theatrical group of people.

With this project, Malmberg and Shellen are clearly just as interested in the production as they are in the people there. When they show the play being rehearsed, they focus on the faces of those watching just as much as the content that’s on the stage. “Spettacolo” in turn feels broad with its desire to people-watch and sum up a town’s entire theatrical history, but it touches enough upon art’s ability to imitate life and vice versa. It’s a charming look at a group of people and fading tradition we may not have heard about otherwise, and clues us into how they create their sense of community.