Most girls come here pregnant

Some by their own fathers

Bridget got that belly

By her parish priest

We’re trying to get things white as snow

All of us woe-begotten-daughters

In the steaming stains

Of the Magdalene laundries

— Joni Mitchell, “The Magdalene Laundries”

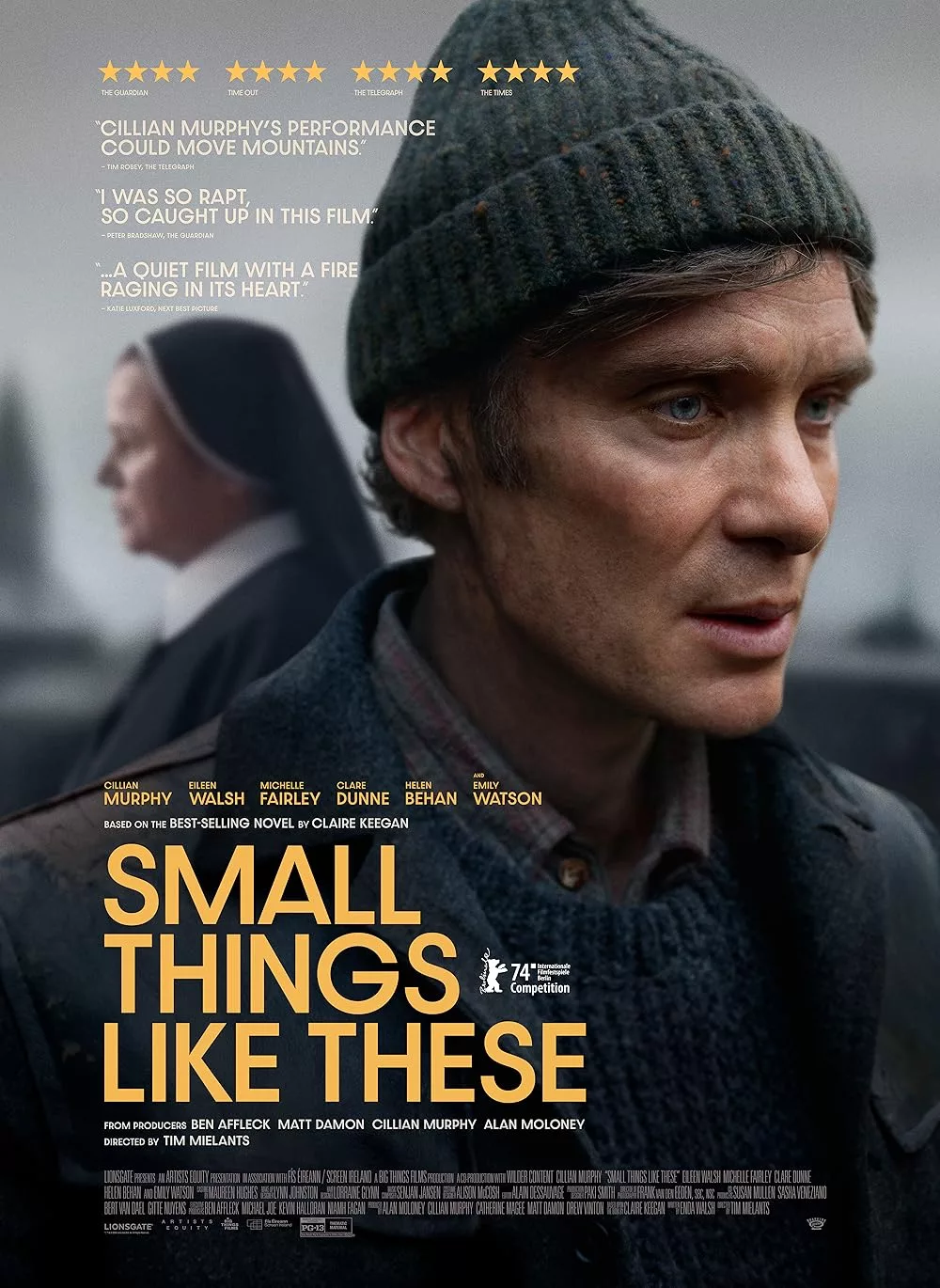

“Small Things Like These” starts and ends with the sound of church bells ringing. The first time you hear the bells, it establishes the atmosphere of the chilly, humble Irish town, its inhabitants busy preparing for Christmas. But when you hear those bells at the end, they sound very different, a reminder in the air of the Catholic Church’s dominance, which we have seen at work in this powerful, quiet film about Ireland’s shameful “tradition” of the “Magdalene Laundries.”

The Magdalene Laundries were a sinister interlocking system of orphanages, homes for “fallen women” and unwed mothers, and workhouses, where women and girls provided cheap labor for the surrounding community. They were, essentially, prisons. The babies born to these mothers were put up for adoption, often against the mother’s will. Babies made these institutions a nice profit. Sometimes, girls were locked up because they were pretty and/or flirtatious and perceived as seductresses. This monstrous system was run by religious orders, majority Catholic, like the ironically named “Sisters of Mercy,” or “Sisters of our Lady of Charity of the Refuge,” and subsidized by the state. The abuse – physical, mental, sexual – endured by the women imprisoned in these places was horrific. The laundries were not dismantled, shockingly, until the mid-1990s. The scars remain.

Directed by Tim Mielants, “Small Things Like These” is based on Claire Keegan’s slim 2020 novel of the same name. (2023’s “The Quiet Girl,” nominated for Best International Film, was also based on a short story by Keegan.) Adapted for the screen by Irish playwright Enda Walsh, “Small Things Like These” doesn’t veer from the book at all. Nothing is added, and I clocked only one thing subtracted. Keegan’s writing is spare and controlled: she gets a lot done in 116 pages, and Walsh’s adaptation captures the suggested interiority of the story. How does one suggest interiority when the character almost never puts his feelings into words?

As Bill Furlong, Cillian Murphy provides the answer. This is a marvel of a performance, extremely expressive and yet deeply inward-looking. When the depths are stirred, you can’t see the bottom. Bill is married to Eileen (Eileen Walsh), and they have five daughters. He supplies coal to the community, dropping off heavy bags around town, scrubbing his hands when he gets home. He is quiet but alert. He notices things: a shivering barefoot boy drinking a bowl of milk left on a stoop, a woman resisting a drunken oaf trying to kiss her. So when, during a routine drop-off at the convent on the hill, he glimpses a screaming girl being dragged to the front door by, presumably, her mother, he freezes, the girl’s terror slicing him open. Bill can’t un-see what he saw. He looks at his five daughters differently when he gets home. They are safe, but they are at risk because they are girls. He wants to protect them. He doesn’t know how to talk about this with his wife, although he tries. (In a nice dovetail, the excellent Eileen Walsh was in the harrowing “The Magdalene Sisters” (2002), where she gives a performance so brilliant, and so upsetting, I don’t know if I could endure it again. The sound of her screaming “You are not a man of God! You are not a man of God!” will haunt me to the end of my days.)

At this point, Bill could maybe go back to the way things were before, but not after he discovers a girl (Zara Devlin) locked in the convent coal shed, freezing, bruised and bloody. This is how the icy eyes of Sister Mary (Emily Watson) train themselves on Bill for the first time. He is offered tea in her office. Sister Mary’s language is pleasant on the surface, but it is impossible to miss the veiled threats. He knows he is being warned. This woman, who runs not only the convent but the girls’ school next door (which Bill’s daughters attend), has enormous power. He knows his youngest girls might pay the price if he “tells” what he saw. This is what absolute power looks like.

Mielants often shoots Murphy from behind, his face turned from the camera. This creates an almost detached association with him – like Bill is unknowable and remote, perhaps even a distracted daydreamer. The approach pays off tenfold when we finally get closeups of his face and we can see just how much life – and people – their pain, vulnerability, beauty, evil – affects him. There’s trauma in his past too. The wounds are not healed. Trauma recognizes trauma.

Mielants also uses a couple of 360-degree pans, showing the world through which Bill moves, the convent hall, the town square. There’s nothing flashy or showy, every visual has a purpose in the story. The sound design is specific (distant voices, babies crying far away, 1980s cartoons in the next room), but there are moments when the sound drops out, leaving only Bill’s breathing, each inhalation filled with the things he can’t say.

Bill’s backstory comes in a series of flashbacks, but they are handled so artfully I didn’t even realize the first one was a flashback. Child Bill (Louis Kirwan) lived with his mother Sarah (Agnes O’Casey) at a big house owned by a Mrs. Wilson (Michelle Fairley). Sarah was employed as a maid and is first seen weeping as she washes Bill’s coat, stained with spittle from the kids who jeered at him for being illegitimate. Mrs. Wilson is kind, and the farmhand Ned (Mark McKenna) is Bill’s friend. Who is Bill’s dad? He tries to explain to Eileen why the convent scene upset him. If Mrs. Wilson hadn’t taken in the two of them, his mother would have ended up in one of those places, and Bill would have been given away for adoption. It’s not “none of our business” what goes on up there. It has everything to do with us, with the girls, with the system we are supporting by our silence.

In his memoir, the great Irish novelist John McGahern described growing up in 1940s-50s Ireland:

“By 1950, against the whole spirit of the 1916 Proclamation, the State had become a theocracy in all but name. The Church controlled nearly all of education, the hospitals, the orphanages, the juvenile prison systems, the parish halls. Church and State worked hand in hand.”

And so, by the end of “Small Things Like These,” the church bells don’t sound like a call to prayer or a joyful expression of faith. They sound, instead, like a warning: “Remember. We are always watching.”