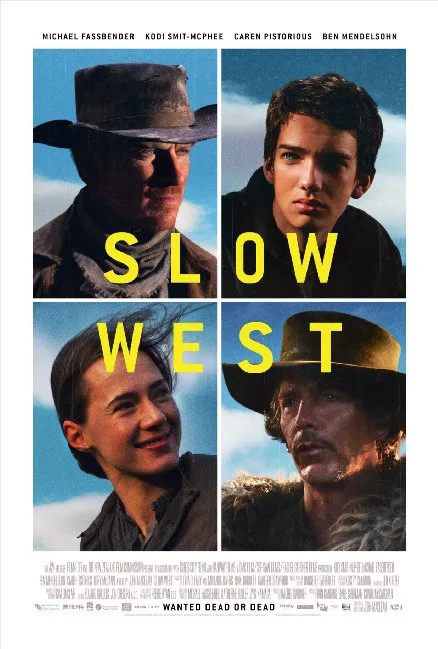

“Slow West” must be counted one of the most unintentionally ridiculous Westerns to come down the pike in a long, long while. From first till last, this tale of a hard-boiled bounty hunter helping a Scottish lad on his quest to find the woman he loves, who’s on the lam in the old West, is a tissue of creaky contrivances and outright absurdities.

Debuting director John Maclean is a Scottish musician, which no doubt helps explain some of the film’s peculiarities. The British movie’s production notes reveal that his knowledge of the American West derives from reading authors like Mark Twain and watching Western movies, both classic and modern. That’s one way of approaching the genre, but it’s perhaps not as advantageous as incorporating a little knowledge of the actual place and the people who once inhabited it.

Granted, from Edwin S. Porter’s “The Great Train Robbery” (1903) on, Westerns have blended one part factualness to three parts fantasy and romance. And European directors from Jan Troell to Sergio Leone have done credible jobs in turning the genre to their own ends. But such filmmakers have usually had a firm grasp either of the region’s history or its particular mythology; Maclean’s work suggests little familiarity with either.

One detail which may seem trivial at first glance but which stands for larger deficiencies is that the film’s Scottish boy-hero, Jay Cavendish (Kodi Smit-McPhee), is shown crossing the Great Plains on horseback without a hat. Do you suppose any male in the 19th century ever did such a thing? Not very likely, for an obvious reason: a real-life Jay Cavendish, with his milky Scottish pallor, would have been broiled lobster-red on the first sunny day.

This is the kind of minor weirdness that can throw a viewer mentally out of the film and into a thicket of questions. Did Maclean and his collaborators not realize their decision would call attention to itself? Was it intended to say something, about either the film or its protagonist, or did it come from the thought, say, that “Kodi has nice curly hair, he’ll look cuter if he’s not wearing a hat?” In fact, considerations of cuteness, while not usually a factor in westerns, seem to have played a significant role in the making of “Slow West.”

Another detail. In a couple of scenes we see walls plastered with “Wanted” posters, some of which contain the faces of real-life 19th century Americans such as Robert E. Lee. Here again, you’re thrown out of the film and obliged to ask, Did the Brits making this film not know these were actual people whom American viewers would recognize? Was using their faces an inside joke, an attempt at some kind of commentary, or just a goof?

To turn from details to larger matters: The film’s central relationship, that between 17-year-old Cavendish and bounty hunter Silas Selleck (Michael Fassbender), is unbelievable from the first. Jay meets the gunslinger just after we see him kill some guys, which makes it very clear that he’s a predatory bad-ass who’s not shy about using lethal force if it suits him. Jay offers Silas some money to accompany him west. So why wouldn’t the bad-ass simply knock the kid over the head—or shoot him—and take his money?

The only realistic answer to that, it would seem, is that Silas is a walking absurdity, the male equivalent of the Whore With a Heart of Gold: the Bad-Ass Who’s Really a Decent Guy Underneath. (Shane, come back!)

Maclean must’ve have realized early on that, since both characters are two-dimensional constructs, their relationship couldn’t go very far, so he understandably separates them for a good chunk of the story. When they reconvene, we get what is perhaps the film’s most famous image: Silas shaving Jay with a Bowie knife. This too provokes questions: Would a real 19th century bad-ass really shave a dewy-cheeked lad—with all the intimacy that implies but no evident erotic interest—as opposed to telling or showing him how to do it himself? Unlikely, but you have to admit the image is cute, and cuteness counts for a lot in this fictional universe.

A few other things that struck this reviewer as noticeably credulity-straining:

- A character goes to sleep next to a large covered wagon that contains all sorts of gear. The next morning he wakes up to find the wagon and many of his possessions gone. Could someone who’s not drunk really sleep through the moving of such a large and undoubtedly noisy vehicle?

- A husband and wife are gunned down in an attempted robbery in a remote locale, leaving behind two children. Two other characters, who’ve been presented as sympathetic, simply ride off without mentioning the kids. Really, would neither of them have said, “Hey, what about these tykes we’re leaving to die in the middle of nowhere?” (This scene serves to set up a cuteness moment late in the film: that’s its only semblance of dramatic logic.)

- A couple who are on the lam, fleeing murderous pursuers, build a house in the middle of a field. That location is obviously intended to help them spot interlopers, but when have ever you heard of people on the run stopping and building a house?

- A character is wounded not once but twice by one of the largest rifles I’ve ever seen in a movie; it’s almost bazooka-sized, with bullets the size of tall beer cans. Hits from a real weapon of this caliber would, of course, tear a man’s body apart. But this guy isn’t that hurt; not long after, he’s good as new.

Certainly, realism and believability don’t count for everything in a genre as fanciful and imagination-dependent as the western. But too many howlers like the countless ones in “Slow West” and a viewer’s suspension of disbelief can be completely shredded. Ultimately, it may not have been the filmmakers’ wisest decision to shoot their nominally Colorado-set movie in New Zealand—i.e., about as far from the real American West as you can get. (Nevertheless, the shooting location does provide some very scenic landscapes for Robbie Ryan’s gorgeous cinematography, the movie’s strongest asset.)

Finally, what is the film’s title supposed to mean? Sure, it’s a play on “Go West (young man).” But the West we see in “Slow West” isn’t noticeably slower or faster than that in other westerns. So it means nothing – but it is kind of cute, wouldn’t you say?